IOG Economic Intelligence Report (Vol. 2 No. 21)

The latest regulatory developments on economic security & geoeconomics

IPEF on the Rocks: It appears the United States is stepping back from talks on the trade pillar in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), putting the future of the agreement in doubt. IPEF is the Biden administration’s proposal for U.S. economic engagement with the Indo-Pacific region given the political difficulty of joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership. IPEF consists of four pillars comprised of a trade pillar, a supply chain resiliency pillar, an infrastructure & clean energy pillar, and a tax & anticorruption pillar.

The negotiating partners have made progress on three of the four pillars and had gathered in San Francisco this month to finalize the trade pillar which would effectively complete the agreement. It now appears that it won’t be possible to reach an agreement on the trade pillar following Senator Sherrod Brown’s request that the pillar be dropped altogether due to the lack of enforceable labor provisions in IPEF. Brown is competing for reelection as a Democrat in a state that supported Trump in the last two elections, and many in the Biden administration believe that those losses are at least partly due to Democrats’ embrace of trade liberalization. For the Biden administration, the hope is that they can support Brown’s reelection campaign by taking trade liberalization off the table as a potential issue.

Additionally, U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai said last month that the United States is withdrawing its support for key U.S. digital trade proposals, including those in IPEF, in order to allow Congress an opportunity to enact stronger regulations on technology. This has led to disagreement in the U.S. government over the future of U.S. digital trade policy, given that Ambassador Tai did not suggest proposals for new positions or offer a timeline for when new proposals may be made available. Politico has reported that the Commerce Department and State Department, as well as some voices in Congress, have concerns with the apparent pivot and lack of clarity going forward.

APEC Outcomes: At the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in San Francisco November 11-17, twenty-one Asia-Pacific economies released a statement calling for reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The joint statement called for “necessary reform to improve all of the WTO’s functions, so that members can better achieve the WTO’s foundational objectives and address existing and emerging global trade challenges.” There was also an agreement on the “ San Francisco Principles Integrating Inclusivity and Sustainability into Trade and Investment Policy”, a nonbinding agreement to support cooperation on communication, information sharing, and environmental sustainability.

China & Japan Open Channel on Export Controls: On November 15, China and Japan announced an agreement to establish a dialogue channel on export controls. The goal is to hold annual director-level talks between the two countries on controls like China’s restrictions on the export of graphite and germanium in order to avoid possible escalation.

Rapidus Expands in Silicon Valley: Japanese government-supported chipmaker Rapidus announced that will open a base in Silicon Valley by the end of March 24 to produce 2-nanometer chips in collaboration with IBM. The plan was announced at a meeting in San Francisco organized by the Japanese government to assemble semiconductor and AI firms to discuss supply chain resiliency and increasing supply capacity of critical technologies. Rapidus and the University of Tokyo also announced that they would partner with French research institute Leti on the development of 1-nanometer chips. Such chips would boost computer power efficiency by 10-20 percent and are expected to enter the market in the early 2030s.

BIS Dropping Some Sanctions: The Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) announced that it’s dropping sanctions on one of the Chinese government institutes connected to human rights abuses of China’s Uyghur minority, effective November 16. Politico reports that in exchange for dropping sanctions, the Chinese government promised to warn its companies to stop making fentanyl, an illicit drug responsible for the deaths of thousands of Americans.

Analysis: The Biden Administration Checks Out on IEPF

For most of the year, Biden administration officials have patronizingly dismissed trade liberalization agreements as the old way of doing things and snapped back at any pushback as representing old ways of thinking. The Biden administration was going to demonstrate that there was a new way of doing trade that didn’t rely on tariffs or market access and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), Biden’s answer to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), was how they were going to demonstrate that to the doubters. Instead, with the announcement that an agreement couldn’t be reach on IPEF’s trade pillar and USTR’s pivot on digital trade rules, the new model seems to be about as successful as the old model – and has been tripped up for a lot of the same reasons.

If this is the end of IPEF, the reasons will be predictable – and the reasons that the skeptics have pointing to throughout the process. One of the key reasons that the Biden administration took tariffs and market access off the table was to avoid congressional ratification. But by closing off all talk of market access, Biden administration negotiators also closed off the possibility of creating enforceable commitments – and the lack of enforceable labor protections is precisely the reason why Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) expressed his opposition to IPEF’s trade pillar. By taking market access off the table, the Biden administration basically took away any chance of securing the enforcement mechanisms they need. Goodwill isn’t enforceable. It’s difficult to shape rules and entrench a rules-based trading order if countries don’t have an incentive to change their behavior, especially given the standards the United States is requesting went beyond those in TPP. Leaving out market access also would have made any potential economic gains insignificant (and IPEF economies represent 40 percent of global GDP) and meant that there weren’t meaningful domestic stakeholders in the United States with an incentive to see IPEF secured.

But even in their efforts to avoid Congress, they still found themselves blocked by congressional pressure. The administration never pursued renewal of Trade Promotion Authority and was evasive or contradictory as to whether a final agreement on IPEF would need any kind of congressional approval, or if it could be implemented as an executive agreement. Needless to say, Congress had issues with this approach, as it usually does when it feels left out of the picture, and so IPEF has few friends on Capitol Hill. The other approach – implementing IPEF as an executive agreement – leaves it unclear as to how much IPEF’s provisions would be legally binding or to what extent its terms would be enforceable.

It’s important not to oversell the cynicism towards IPEF – it’s not ideal (that would be U.S. entry into TPP which is out of the picture) but it’s still something, and for all the skepticism that IPEF is only a “plan B”, the negotiating countries are still taking it seriously. Japan, as it did with TPP, is offering to keep IPEF alive but that will be a hard job given the domestic political constraints in the United States. Finding an institutional vehicle to keep the United States institutionally tied to the Indo-Pacific will probably remain a priority among U.S. economic partners across the Pacific. This might not yet be “gut check” time when U.S. partners begin having serious conversations with themselves about how much they can count on the United States as an economic partner, but that moment is probably coming over the horizon.

The charitable interpretation of what happened is that there’s no way for the Biden administration to win – they tried to thread the needle between entrenching U.S. economic engagement in the Indo-Pacific while avoiding a Congress and Democratic Party disinclined to trade liberalization and found that the degree of difficulty was too steep. While IPEF was probably the most that could be hoped for given the domestic political constraints on the United States, the effort to find a middle way still resulted in getting stuck. By trying to make everyone happy – Congress, domestic exporters, Indo-Pacific partners – it ended up making no one happy. IPEF was already a low bar with its restrained ambitions and lack of commitments, but even that much isn’t achievable for the United States.

The less charitable interpretation is that the Biden administration badly botched the politics and the diplomacy and has set back U.S. strategy in the region. The ultimate result is a giant, gaping whole in the Biden administration’s international strategy. If it weren’t for export controls and sanctions, the Biden administration wouldn’t have an international economic policy at all. Beyond simply being a problem of economics, it undercuts the administration’s entire global strategy by relying almost exclusively on defense policy and economic coercion rather than building an architecture to facilitate cooperation. It’s fair to be concerned about elections when you’re a democracy and the challenge of simultaneously navigating domestic politics and international diplomacy is perennial. But if the Biden administration and its candidates in Congress survive the 2024 election, they will need to urgently develop a geoeconomic strategy that builds an order because the current trajectory of “all guns and no butter” that almost exclusively relies on defense strategy and economic coercion will make the region poorer and less stable. They promised a new way of doing things and couldn’t deliver – if they’re so convinced this is the way forward, they need to show that this can work.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this IOG Economic Intelligence Report do not necessarily reflect those of the API, the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

API/IOG English Newsletter

Edited by Paul Nadeau, the newsletter will monthly keep up to date on geoeconomic agenda, IOG Intelligencce report, geoeconomics briefings, IOG geoeconomic insights, new publications, events, research activities, media coverage, and more.

Visiting Research Fellow

Paul Nadeau is an adjunct assistant professor at Temple University's Japan campus, co-founder & editor of Tokyo Review, and an adjunct fellow with the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He was previously a private secretary with the Japanese Diet and as a member of the foreign affairs and trade staff of Senator Olympia Snowe. He holds a B.A. from the George Washington University, an M.A. in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and a PhD from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy. His research focuses on the intersection of domestic and international politics, with specific focuses on political partisanship and international trade policy. His commentary has appeared on BBC News, New York Times, Nikkei Asian Review, Japan Times, and more.

View Profile-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

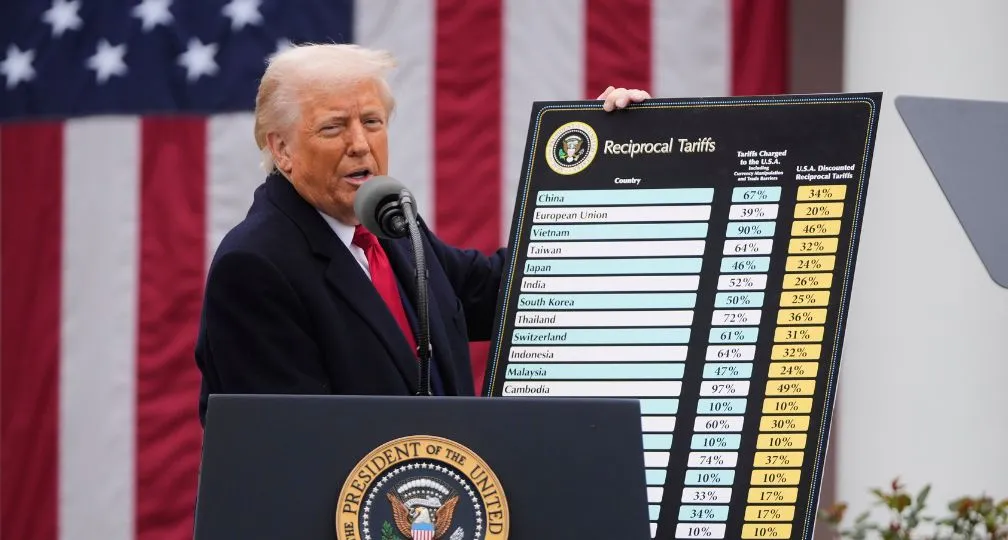

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06

Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25