The Opportunity and Duty for Japan’s Defense Exports Amid the Demand-Pulled International Defense Economy

Likewise, but slightly differently, it would be the defense industrial policy in that the two elements of security and economy are overlapping. The defense industry is an indispensable element of sustaining national security in the sense that it has the function of manufacturing defense equipment. On the other hand, it also has an economic aspect in which its function is dependent on companies. Therefore, just as economic security is a concept that symbolizes the growing awareness of the importance of economic aspects in national security, it is becoming increasingly important to take into account such aspects of the defense industry when considering its sustainability amid the situation where procuring defense equipment becomes more costly and requires more advanced technology. However, conventional discussions on the defense industry have not given enough emphasis on its economic aspects. Specifically, there has been a lack of consideration for maintaining the defense industry in a sustainable manner as an industrial sector. The most obvious manifestation of this is the former Three Principles on Arms Exports, which had restrained the overseas transfer of defense equipment, and the Three Principles on Overseas Transfer of Defense Equipment, which slightly expanded the options for exports.

Measures to strengthen the defense industry as a whole, including not only defense exports but also the entry of new companies with advanced technologies, are discussed in detail in the report “Comparative Study of Defense Industries: Autonomy, Priority, and Sustainability,” published in 2023 by the Institute of Geoeconomics. On the other hand, in this article, I analyze the opportunities for Japan and the expectations of its role in exporting defense equipment overseas, with particular attention to the trends in the international defense market.

International Defense Market Led by a Strong Supply Side

In general, countries with large defense expenditures tend to have large arms exports. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the top 10 large defense spending countries in 2022 were, from top to bottom, the United States, China, Russia, India, Saudi Arabia, the UK, Germany, France, South Korea, and Japan while the top 10 largest arms exporters in the five years from 2018-2022 were the United States, Russia, France, China, Germany, Italy, the UK, Spain, South Korea, and Israel[1]. Of the top 10 defense spending countries, only India and Saudi Arabia, which have weak domestic defense industrial bases, and Japan, which has been restraining arms exports, are not among the top 10 arms exporters. The development and production of defense equipment require a large initial investment and advanced technologies while the scale of economy with a large demand does not usually apply, which means that it is important to expand overseas demand. Therefore, it is evident from these international trends that overseas exports are an indispensable means of maintaining a defense industry of a certain scale domestically.

In addition, while the scale of global arms exports has been increasing in recent years, the scale of US arms exports has been growing at a faster pace than that of the rest of the world. The scale of arms exports from the world’s top 100 countries has increased 1.8 times over the past 20 years while that of the United States has tripled over the same period, accounting for 40% of the world’s total[2]. While the increase in the size of global arms exports represents an increase in demand for arms, the significant increase in the share of US products with a technological edge suggests increased competition on the supply side. When looking at the US Department of State release, the size of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) increased by 55.9% from $51.9 billion in FY2022 to $80.9 billion in FY 2023[3]. Of this amount, $62.3 billion was paid for transactions that were not funded by the federal budget (such as grants or loans), but this is still significantly higher than the previous year’s total.

By contrast, it is not easy for a latecomer in arms exports to rapidly increase its market share in an international market that has been dominated by strong suppliers. Thus, even after Japan formulated the Three Principles on Overseas Transfer of Defense Equipment in 2014, which reversed its previous policy of uniformly restricting commercial arms exports, it has been unable to expand its overseas exports due to its lack of strength as a latecomer, combined with the limited areas of equipment which can be exported.

Revision of the Three Principles on Overseas Transfer of Defense Equipment to Enable Participation in International Supply Chains

Out of an awareness of the crisis over this situation, the government revised the Three Principles on Overseas Transfer of Defense Equipment and its Implementation Guidelines in December 2023. The revised Three Principles emphasize that the overseas transfer of defense equipment is an important policy tool for creating a desirable international security environment and for supporting countries that are suffering from aggression. This is based on the recognition that, in addition to responding to aggressors, defense equipment transfers would contribute to improving the security environment surrounding Japan by building medium-to-long-term relationships with the recipient countries through equipment maintenance, education, and training. Moreover, the Three Principles stipulate that overseas transfers would contribute to the improvement of its defense capability and the maintenance and enhancement of the defense industrial base, which is described as a defense capability itself. This may be a sign of the recognition that ensuring the sustainability of the operations of defense companies is essential for strengthening the defense industrial base, and that defense equipment transfers will contribute to ensuring such sustainability.

The revision also allows Japan to directly export indigenously manufactured parts and technologies incorporated into jointly-developed products, and to export licensed products to the licensor countries, which was previously limited to the exports of licensed parts to the United States.

On the other hand, as of the end of 2023, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito were unable to reach an agreement in the ruling party discussions on broadly allowing the direct exports of jointly developed products from Japan to the third countries (other than the co-development partners) and the exports of finished products developed indigenously, beyond those related to the so-called “five categories” (rescue, transport, warning, surveillance, and minesweeping).

In light of the above, the recent review of the Three Principles was carefully designed in order not to block deals with pragmatic benefits while still keeping reluctance to take a bold initiative in exporting finished lethal products. In particular, regarding international joint development, it can be said that the review is aimed at reducing the risk of undermining the overall benefits of the joint projects through Japan’s veto to third-party transfers initiated by partner countries[4]. In addition, the full lifting of the ban on exports of licensed products and the lifting of the ban on component-level exports are realistic strategies for a latecomer to exports as they allow the Japanese defense industry to get integrated into the international supply chain by utilizing established markets already explored by foreign defense primes.

On the other hand, unless direct exports of jointly developed finished products from Japan to third parties and exports of equipment beyond the five categories are made possible, it will remain difficult for Japanese defense companies to leap forward as international defense primes. To examine the remaining issues in this regard, the ruling parties are resuming discussions on the second phase of the revision of the Three Principles early in 2024.

Indeed, the revision at the end of 2023 has significantly increased what the Japanese defense industry can do. Nevertheless, the author argues that the remaining issues mentioned above should be resolved as early as possible. There are three reasons for this.

Emergence of a Demand-Pulled Defense Market

First, defense trade, which used to be a supply-pushed market where countries with large domestic defense industries competed with each other to expand their exports, is now turning into a demand-pulled market. Signs of this have been seen for several years due to the recent great power competition. But it has become even more pronounced with the protracted war in Ukraine.

The United States, the largest assistance provider to Ukraine, had not maintained a large inventory of ammunition and portable anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, which are important in a war of attrition on the ground. It was because the US military had adopted to a force structure optimally designed for a short and decisive war through overwhelming military capabilities and technological superiority. As a result, when ammunition and missiles are in short supply to provide weapons in response to the war of attrition, their components and production lines have become bottlenecks, requiring long lead times to increase production[5]. In addition, ammunition and missile inventory shortages are a common issue not only in the United States but also in NATO members in Europe[6]. Furthermore, there is strong Republican opposition in the US Congress to arms aid to Ukraine, particularly in the House of Representatives, and there is little prospect of securing the stable funding necessary for such aid. As a result, as of January 2024, Russia can expend 10,000 artillery rounds per day, while the Ukrainian side can only consume 2,000 rounds per day, leading to the imbalance in firepower which is further expanding[7].

In this regard, the National Defense Industrial Strategy (NDIS) released by the US Department of Defense in January 2024 identifies the lack of US defense production supply chain resiliency as a major challenge as it has emphasized efficiency through “just-in-time production” without excess inventory. The NDIS also recommends an increase in the supply chain visibility, investment in excess production capacity, and international defense production cooperation[8]. The fact that the NDIS calls for cooperation with allies and partners in addition to its emphasis not only on the quality but also the quantity and redundancy of defense production represents in a sense an opportunity for Japan, a latecomer to exports, to participate in the US market. Such participation will not only contribute to the maintenance and strengthening of Japan’s defense industrial base but will also indirectly support Ukraine, which is being placed in a disadvantageous position due to the shortfalls of ammunition and equipment.

Furthermore, as the NDIS acknowledges, the US defense supply chain becomes more vulnerable to risks as it goes to lower tiers. If so, the possibility for Japan to participate in the US market at the component level may increase shortly. However, the international demand for defense production, including from Ukraine, is not limited to participation in the US supply chain. In particular, with the passage of the Ukraine assistance budget in the US Congress in jeopardy, Japan might be called upon to play a larger role, including in the export of finished products though it is realistic to assume a slow and incremental process.

War of Attrition as a Result of Stalemates of Technological Competitions

Secondly, the protracted conflict in the form of attrition indicates that it may not be limited to the specific characteristics of the war in Ukraine. For instance, in the CSIS report on the Taiwan war game published in January 2023, a shortage of standoff missile inventory in US forces was observed in the iterated games[9].

On this point, in the strategic studies literature, it is pointed out that when modern armies engage in combat, they need to balance the trade-off between projecting firepower and advancing to secure territory and increasing survivability by dispersal and concealment. Recent studies, however, have shown that the equilibrium of this trade-off is moving in the direction of more emphasis on ensuring survivability due to the evolution of defense technologies in this century which have improved precision and lethality of firepower[10].

As a result, troops need to be widely dispersed and ensure that they are not swiftly neutralized by the enemy’s missiles, drones, and other precision firepower. Conversely, however, this makes it more difficult than ever to penetrate the enemy’s defense lines and secure territory through the concentration of forces. In fact, in the Ukrainian war, it was pointed out from an early stage that the Ukrainian troops were dispersed more compared with the conventional Western standard to increase survivability[11]. Furthermore, against a dispersed enemy that is difficult to neutralize with concentrated firepower, extremely large quantities of ammunition will be required, and there will be huge risks of civilian casualties.

Based on these observations, if denial military technologies, such as missiles and drones, which can degrade enemy forces but do not directly contribute to holding territory, are developed and the dyad to the conflict has comparable capabilities in this regard, it would be inevitable to see a stalemate. If so, the unprecedented use of drones and missiles in the war in Ukraine would be by no means unrelated to the fact that war of attrition has become a common practice. If the United States and China were to balance similar asymmetric capabilities, the conflict would likely be prolonged, with the quantity of equipment and ammunition becoming decisively important. While it has been discussed so far that future warfare would involve the short and decisive war enabled by transformational technologies, hybrid warfare, or non-kinetic warfare which may not accompany physical destruction, the fact that wars of attrition are still being waged between parties with comparable capabilities indicates the need to review the current trends from a longer-term and historical perspective.

In any case, as long as it is recognized that the contemporary form of warfare demands the munition quantity, increasing redundancy in production capacity to prepare for a war of attrition will not be a temporary demand, but rather a medium-to-long-term requirement. Therefore, as Japan is located near the potential conflict zones of the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula, it will be necessary to respond to the international demand for such redundancy from a medium to long-term perspective.

The Need for Derisking in the Supply Chain

Thirdly, the concept of derisking concerning China discussed from an economic security perspective, will have a similar impact on the international defense supply chain in the future. The US NDIS cited above also points out a concern about dependence on potential adversaries for materials, technologies, components, and capital. The importance of supply chain visibility and defense production cooperation with allies and partners is also discussed from this perspective. Some of the critical minerals of which China accounts for a large supply share are also essential for the production of defense equipment, such as rare earth materials, and a situation in which the defense supply chain is bottlenecked by an adversary that the United States and its allies are attempting to deter would not be strategically favorable[12].

At the same time, the NDIS is also concerned about the tapering off of the skilled labor force involved in the defense industry, and it will not be easy to onshore the supply chain once it has gone offshore, even if the government rapidly invests money to strengthen the industrial base.

Of course, Japan is not immune to the problems of supply chain dependence on foreign sources and labor shortages. However, efforts to mutually complement each other’s vulnerable supply chains with allies and partners including the United States are likely to become even more required in the future.

In this regard, it would be most realistic to start derisking efforts in the defense supply chain with cooperation on component supply. On the other hand, it is also important not to exclude all options, including the export of finished products and local production in allied and partners. The first thing to do as a derisking measure in the area of defense equipment may not either be investment or subsidies, but to remove barriers that block opportunities to mutually eliminate vulnerabilities in their own countries and those of their allies. From this perspective, not only the transfer of equipment parts which was made possible by the revision of the Three Principles at the end of 2023, but also the export of components that are installed on large platforms such as aircraft and vessels (those that can independently perform their functions are not regarded as parts in the Three Principles) should be made fully possible. It will also be important for the Japanese government to encourage the United States to allow Japanese companies to participate flexibly in its government procurement programs involving sensitive information.

In the survey of 100 Japanese companies on economic security conducted by the Institute of Geoeconomics at the end of 2023, Japan (domestic return) as well as allies and friendly countries such as the United States, India, and the EU were listed as the most important countries as destinations for diversification of supply sources. In the context of the overseas transfer of defense equipment, there is a growing demand for such “onshoring” or “friend-shoring” from the same perspective. In addition, there is the unique circumstance that the effect of the revision of the Three Principles has been unprecedentedly strong for defense equipment, for which international demand is expected to grow over the medium-to-long term, even though the exports in this field have traditionally been extremely restrained in Japan. Responding to this situation swiftly will become an effective means of strengthening the defense industrial base, and at the same time, it will help fulfill its duty to take the initiative to shape and maintain a desirable international security order.

参考文献

- [1] SIPRI, SIPRI Yearbook 2023 (SIPRI, September 2023).

- [2] This is based on SIPRI’s trend index value (TIV) which measures the size of arms exports. SIPRI, Arms Transfers Database, https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers.

- [3] Department of State, “Fiscal Year 2023 U.S. Arms Transfers and Defense Trade” (January 29, 2024), https://www.state.gov/fiscal-year-2023-u-s-arms-transfers-and-defense-trade/.

- [4] Even under the Three Principles prior to the revision in 2023, there was no uniform ban of the transfer of finished products incorporating Japan-origin parts and technologies to a third country by the partners of joint development, and it was possible to give prior consent after deliberation. Especially in the case of participation in an international system of mutual supply of parts (e.g., the participation in the Automatic Logistics Global System (ALGS) for F-35 parts) or exports of parts to a licensor (export of F-100 engine parts for F-15 and F-16 fighters to the United States licensor), a simplified procedure has been adopted to allow third-country transfers by confirming the export control regulations of the destination country, instead of the individual prior consent procedures under the Defense Equipment Transfer Agreement. The revision at the end of 2023, in addition, allows for the direct export of such parts and technologies to third countries in consideration of the possibility that, when the partners of a joint development project transfer a finished product incorporating parts and technologies of Japanese origin to a third country, Japan will be required to export those parts and technologies directly to the third country for maintenance and servicing. Furthermore, these cases (except for cases involving highly sensitive technologies) are added to the list of cases in which the transfer to a third country is permitted under the simplified procedure by verifying the export control regulations of the destination country, without the prior consent process under the transfer agreement. In light of the above, for example, if the finished products of the Japan-UK-Italy jointly developed fighters under the GCAP are assembled as finished products at a factory in the UK or Italy, it is possible for the UK or Italy to export them to a third country with Japan’s prior consent or examination of the export control regulations of the third country. With this regard, however, since GCAP fighters are to be manufactured by a joint venture (JV) of Japanese, British, and Italian companies, a case can be envisioned in which, for exports to a third country, Japan is required to export finished products to it as they perform manufacturing sharing in the “spirit of equal partnership” (Japan-UK-Italy Summit Joint Statement in December 2022). Therefore, it is true that the revision at the end of 2023 still does not provide any measures for these cases, and the Three Principles remain a constraint on Japan’s leading role in discussions of production sharing in the GCAP.

- [5] John Ismay and Eric Lipton, “Pentagon Will Increase Artillery Production Sixfold for Ukraine”, The New York Times (January 24, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/24/us/politics/pentagon-ukraine-ammunition.html; Doug Cameron, “Why Ukraine Hasn’t Been a Boon to U.S. Defense Companies”, The Wall Street Journal (January 31, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-ukraine-hasnt-been-a-boon-to-u-s-defense-companies-11675176026.

- [6] “Europe needs a decade to build up arms stocks, says defence firm boss”, BBC News (February 13, 2024),https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68273449.

- [7] “Ukraine Uses Five Times Less Artillery Ammunition Than Russia – RUSI”, Defense Express (January 8, 2024), https://en.defence-ua.com/industries/ukraine_uses_five_times_less_artillery_ammunition_than_russia_rusi-9125.html.

- [8] Department of Defense, “National Defense Industrial Strategy 2023” (January 11, 2024), https://www.businessdefense.gov/docs/ndis/2023-NDIS.pdf.

- [9] Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan” (Washington DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 9 2023), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/230109_Cancian_FirstBattle_NextWar.pdf?VersionId=WdEUwJYWIySMPIr3ivhFolxC_gZQuSOQ.

- [10] Stephen Biddle, Nonstate Warfare: The Military Methods of Guerillas, Warlords, and Militias (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), chs. 3, 4, and 10.

- [11] Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi, et al., “Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: February–July 2022” (London: Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, November 30, 2022), 53, 62-63.

- [12] Hirohito Ogi, “De-risking Policy in the US Defense Industrial Base”, Journal of World Affairs 71, no.5 (September/October 2023): 51-68 (in Japanese).

Senior Research Fellow

Hirohito Ogi is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) studying military strategy and Japan’s defense policy. Before joining the IOG, Mr. Ogi had been a career government official at the Ministry of Defense (MOD) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) for 16 years. From 2021 to 2022, he served as the Principal Deputy Director for the Strategic Intelligence Analysis Office, the Defense Intelligence Division at the MOD, where he led the MOD’s defense intelligence. From 2019 to 2021, he served as a Deputy Director of the Defense Planning and Programming Division at the MOD. He holds a Master’s degree in international affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), Columbia University, and a Bachelor’s degree in arts and sciences from the University of Tokyo. He is the author of various publications including Comparative Study of Defense Industries: Autonomy, Priority, and Sustainability (co-authored, Institute of Geoeconomics, 2023).

View Profile-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

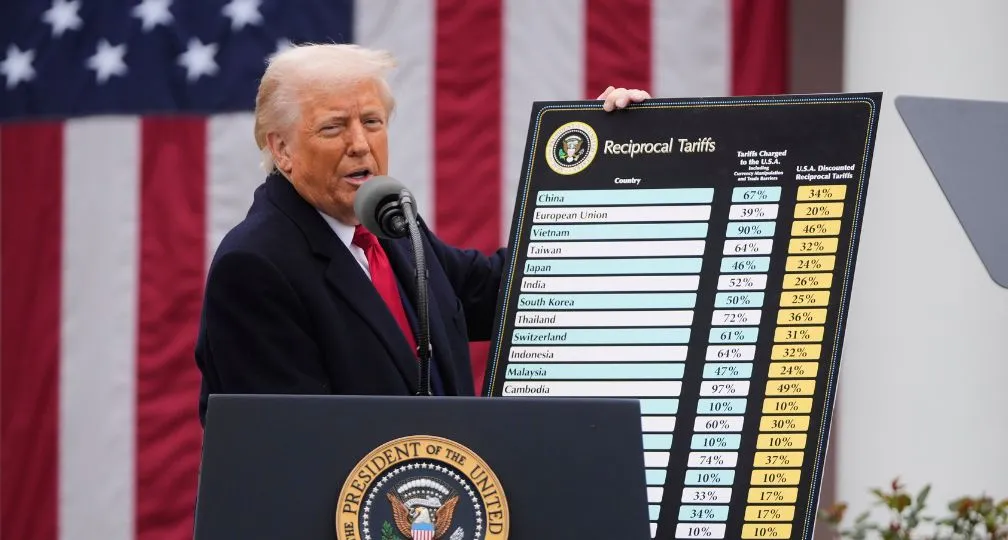

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 After tariffs: Is there a plan to restructure the global economic system?2025.04.03

After tariffs: Is there a plan to restructure the global economic system?2025.04.03