Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) amid US-China strategic competition: The Global South’s agency in era of geoeconomics

Extravagant Spending Amid Economic Challenges

In September 2024, China gathered leaders from all 53 African countries,[1] excluding Eswatini, with which it has no diplomatic ties, for the ninth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC 9) in Beijing—the largest “home-ground diplomacy”[2] event of the year. In his keynote speech, President Xi Jinping proudly declared that “the China-Africa relationship is currently at its best in its 70-year history.”[3] However, in stark contrast to the grandeur of the international conference, China’s economy remains in a slump, with sluggish production, consumption, and investment dragging on growth.[4] Despite these challenges, FOCAC 9 concluded with the adoption of two major agreements: the “Beijing Declaration on Jointly Building an All-Weather China-Africa Community with a Shared Future for the New Era” (hereafter referred to as the “Beijing Declaration”[5]) and the “FOCAC Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027)” (hereafter referred to as the “Beijing Action Plan”[6]). Importantly, the Beijing Declaration praises FOCAC as a model for “South-South Cooperation,” where countries of the Global South help each other achieve development, suggesting that China-Africa cooperation differs from the top-down, donor-driven approach taken by developed nations when engaging with Africa. The Chinese government hailed these as significant diplomatic achievements.

The world has long turned its attention to Africa, which makes up a significant part of the Global South. Many countries have held “Africa+1” summits[7]—such as FOCAC—as a means to strengthen relations with the continent. The trend began in 1993, when Japan took the initiative to launch the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD).[8] Today, numerous countries, including Western nations, Russia, Korea, India, and Indonesia, have followed suit, holding summits to enhance their ties with Africa.[9]

Since the first FOCAC was held in Beijing in 2000, China has hosted the summit every three years, alternating with an African host nation. As China’s presence in Africa surged in the mid-2000s, the international community began paying close attention to the scale and content of China’s aid plans for Africa announced at each FOCAC. At the mid-2010s FOCAC, China unveiled a massive aid package of 60 billion USD, showcasing its strong presence in Africa to both domestic and international audiences. However, in the pandemic-hit FOCAC 8, held online in 2021, China reduced its aid amount for the first time in the summit’s history, pledging 40 billion USD, which surprised both China watchers and those in the international development sector.[10]

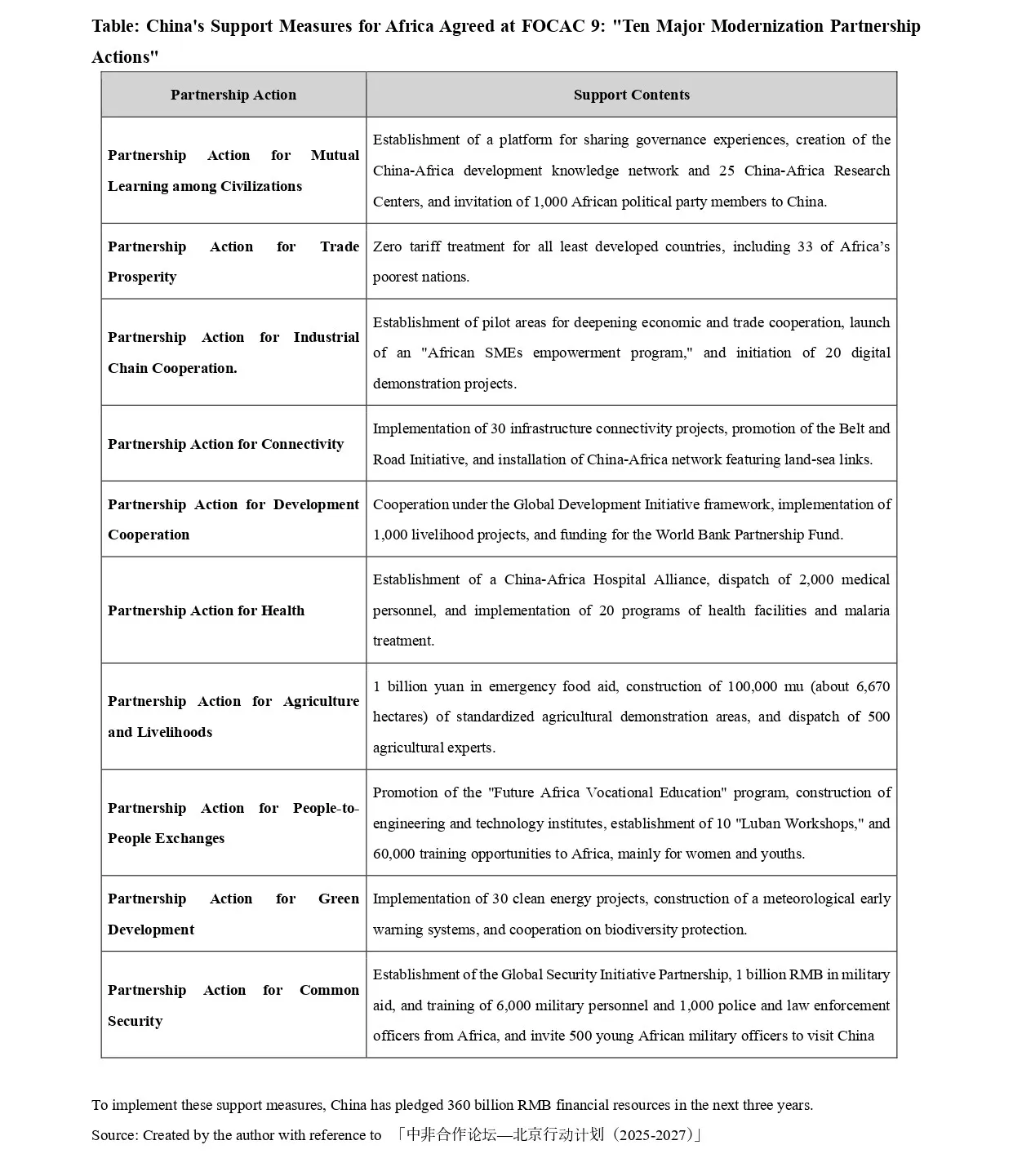

With this year’s FOCAC being the first in-person summit in the post-COVID era, attention again focused on the scale of China’s new commitments to Africa.[11] In the end, China pledged more than 360 billion RMB (about 50 billion USD), surpassing its commitment three years ago by 10 billion USD. However, this also signifies that China, now facing an economic slowdown, has taken on a substantial burden.

What exactly has China gained from this? This article seeks to answer this question from the perspective of geoeconomics,[12] which analyzes the relationship between economic statecraft and the achievement of a nation’s strategic objectives. In doing so, it draws on the “Aid-for-Policy Deal” theory,[13] which examines aid as a bargaining tool used by the donor to secure desirable policy concessions from the recipient. While economic benefits, such as resource rights, are often cited as China’s primary gains from cooperation with Africa, through a geoeconomic lens, this article explores the political gains China has secured through its commitment to massive investments pledged at FOCAC 9.

What Did China Gain from FOCAC 9?

Since the establishment of the Xi Jinping administration, the cooperative measures under FOCAC have incorporated various mechanisms aimed at enhancing China’s international influence both within Africa and globally. In this year’s FOCAC, China incorporated more political objectives into the FOCAC outcomes, particularly in the context of competition with the United States. The outcome documents of FOCAC 9 are filled with language challenging U.S. international leadership across various sectors, including currency, trade, peace and security, and global governance.

In terms of currency, much attention has been drawn to the sheer amount of “over $50 billion,” but what stands out in this year’s pledges is the use of “360 billion RMB.” Previous FOCAC pledges had been denominated in U.S. dollars, but this shift to the Chinese yuan could be interpreted as a move by China to hedge against foreign exchange risks and promote the internationalization of the yuan.[14] While this does not represent a direct challenge to U.S. dollar hegemony, it could at least reduce dependency on the dollar in economic cooperation-related transactions between China and Africa. Moreover, the “Beijing Declaration” condemns and calls for the removal of sanctions imposed by the U.S. and other Western countries on Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. In cooperating with these sanctioned countries, there is a strong need for transactions that do not rely on the dollar.

On the trade front, China promised zero tariffs on all imports from least developed countries (LDCs), including 33 African nations, and President Xi proudly declared that this move would turn China’s vast market into a significant opportunity for Africa.[15] The economic significance of this market opening for the target countries is substantial and is commendable from the perspective of promoting development in Africa’s LDCs. However, expanded access to China’s massive market could also lead to an asymmetrical dependency between the target countries and China, potentially increasing China’s influence over these countries, thus strengthening its geopolitical leverage.[16]

Regarding the multilateral trade system, the “Beijing Action Plan” advocates for “a universally beneficial, inclusive economic globalization.” In the document, China and Africa jointly reaffirmed their commitment to maintaining the core values and basic principles of the World Trade Organization (WTO), opposed decoupling and disruptions in supply chains, and stated their intention to resist unilateral actions and protectionism and shared aim to protect the legitimate interests of developing countries, including China and Africa, while enhancing the dynamism and driving force of global economic growth. As the expansion of global value chains has brought significant benefits to developing countries,[17] a narrative is being woven that it is China that protects the world’s free trade system, which Western powers, led by the U.S., are trying to distort for their own sake.

FOCAC 9 also served as a platform for China to project its political agenda onto the international stage. The “Beijing Declaration” and “Beijing Action Plan” repeatedly refer to “Chinese-style modernization,” a key theme highlighted at the 20th Central Committee’s Third Plenary Session of the Communist Party of China in July. Furthermore, slogans like “African modernization” and “modernization of the Global South” were prominently presented, seemingly elevating the Party’s ideas to international objectives.[18] Additionally, the “Beijing Action Plan” addresses the need for strengthening global governance in areas such as security, artificial intelligence, nuclear energy, biosecurity, economics, finance, anti-corruption measures, climate change, and maritime issues. This underscores China’s intent to advance its engagement in global governance with Africa’s support.

Particularly noteworthy is the contribution of FOCAC 9 in solidifying China’s global initiatives, especially in the security domain. China expressed its intention to establish regional cooperation models for the Global Security Initiative (GSI) in Africa and initiate early collaboration on the GSI. This is one of the global initiatives put forth by President Xi in recent years as part of China’s vision for building a “community of shared future for mankind.” The GSI presents a comprehensive concept of security, calling for global cooperation on security issues.[19] However, unlike other initiatives like the Global Development Initiative (GDI), which focuses on development cooperation and has gained some traction, China’s international influence in the security domain has remained limited, and the GSI lacks demonstrable results.[20] President Xi still wants the GSI to gain traction, particularly in the Global South, and FOCAC 9 provided a platform to demonstrate the practical application of this initiative.

Africa’s Position in the “Aid-for-Policy Deal”

In FOCAC 9, China successfully incorporated its own political goals, influenced by its competition with the U.S., into its cooperation with Africa. From the perspective of the “aid-for-policy deal” theory, it is important to note that China has managed to reduce the costs associated with securing “policy concessions” from the African side, while simultaneously offering large amounts of “aid.” The cooperation items in FOCAC 9, which are favorable to China, were likely easy for the African side to accept. For instance, China’s call to act together in making the current international order, which is led by developed countries, more equitable and just resonated well with African countries, which have a history of colonization and ongoing distrust toward Western countries. Although the narrative of solidarity among Global South countries was easily embraced, China’s cooperation with Africa is not without its challenges. This is framed not as charity from the wealthy, but rather based on the principles of “win-win” and “mutual benefit,” promoting the idea of assistance between developing nations. According to this principle, China is also expected to gain benefits from the cooperation projects, which ultimately leads to the implementation of development cooperation with highly unfavorable commercial loan conditions, setting it apart from the aid provided by developed countries.

That said, China did not achieve everything it wanted in FOCAC 9. In a press conference on September 5, Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated that “China and Africa have agreed to break free from the ‘Small Yard, High Fence’ policy”—a reference to the tightening U.S. export controls—and he emphasized solidarity with Africa in resisting American regulatory measures. However, there is no mention of the “Small Yard, High Fence” in the FOCAC 9 agreement documents, suggesting that the African side was reluctant to explicitly state opposition to a third country like the U.S. in official documents. Developing countries, including those in Africa, are generally reluctant to be drawn into competition between major powers.

The Growing African Agency

Discussions regarding Africa’s ability to assert its agency and fulfill its aspirations in international diplomacy and the global arena, referred to in the African studies literature as the concept of “African agency,”[21] have been ongoing for over a decade. In reality, Africa has increasingly demonstrated a more assertive stance in international negotiations, contrasting sharply with the traditional stereotype of being a weak entity constantly dictated by international organizations and powerful external actors. Now, Africa is leveraging the growing number of “Africa +1” summits to diversify its partnerships[22] and avoid dependence on specific countries, thereby enhancing its agency.[23] If China attempts to impose goals that do not align with Africa’s aspirations as it continues to “politicize” FOCAC, it will likely face difficulties.

The experiences from FOCAC 9 offer valuable lessons for engaging with Global South countries in a world moving towards multipolarity.[24] The U.S. is also pursuing “Africa +1” summit diplomacy through the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, aiming to strengthen relations with the continent, but at this stage it is difficult to claim that it has been more successful than China’s efforts. South African researcher Jana de Kluiver astutely observes that the U.S. strategy is perceived more as an anti-China policy than an Africa policy.[25] Similarly, when Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Japan sought to build a consensus among African nations during TICAD 8 that year to oppose Russia’s aggression.[26] However, many countries in Africa found it unacceptable to publicly condemn Russia, and this attempt was unsuccessful. In an era where Africa’s presence and agency are growing, it is more essential than ever to negotiate and reach agreements as “equal partners.” If a “+ 1” country wishes to extract strategic benefits from “Africa +1” summits, it must align its goals with Africa’s interests to succeed.

Analyzing the World Defined by the Rising Global South Through the Lens of Geoeconomics

This article surveyed how China has extracted political benefits from FOCAC 9 by promising large-scale economic cooperation, which has led to the promotion of the use of the yuan in African countries, increased trade dependence on China, and the propagation of political narratives favored by China. This phenomenon of utilizing economic cooperation as economic statecraft to achieve national strategic interests has been observed not only in China but in almost all donor countries. However, as mentioned earlier, FOCAC 9 witnessed an unprecedented level of “politicization,” which is influenced by the U.S.-China competition, as evidenced by the outcome documents. As Africa’s presence grows, the competition to strengthen relations with it has intensified, prompting countries to further politically leverage economic cooperation. However, African nations are enhancing their agency and are not merely acting in accordance with the intentions of donor countries. For this reason, the perspective of geoeconomics—which analyzes the economic statecraft of various countries and its effects—is becoming indispensable for assessing the increasing activity of “aid-for-policy deals” in diplomacy toward the Global South.

References

- [1] 王毅. 谱写新时代全天候中非命运共同体新篇章 2024-09-16 https://www.mfa.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202409/t20240916_11491690.shtml

- [2] 「ホーム・グランド外交」とは、中国語で「主场外交」で、自国で開催される国際会議等の外交活動を指す。

- [3] 习近平. 携手推进现代化,共筑命运共同体——在中非合作论坛北京峰会开幕式上的主旨讲话 (2024年9月5日 北京)https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202409/content_6972495.htm

- [4] Bloomberg News「中国経済、8月に失速-生産・消費・投資不調で成長目標達成に暗雲」『Bloomberg』2024年9月14日、https://www.bloomberg.co.jp/news/articles/2024-09-14/SJS6WXT1UM0W00(2024年9月14日閲覧)。

- [5] 关于共筑新时代全天候中非命运共同体的北京宣言(全文)来源:外交部 发布:2024-09-05 22:07

https://2024focacsummit.mfa.gov.cn/kms/202409/t20240905_11486048.htm - [6] 中非合作论坛—北京行动计划(2025-2027)来源:外交部 发布:2024-09-05 22:06

http://www.focac.org/chn/ttxx/202409/t20240905_11486047.htm - [7] Soulé, Folashadé. 2020. “‘Africa+1’ Summit Diplomacy and the ‘New Scramble’ Narrative: Recentering African Agency.” African Affairs 119 (477): 633–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adaa015.

- [8] 外務省「TICADの特徴」外務省ウェブサイト、2021年7月13日、https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/af/af1/page22_002577.html(2024年9月18日閲覧)

- [9] Soulé, Folashadé. 2021. “How Popular Are Africa+1 Summits Among the Continent’s Leaders?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 6, 2021. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2021/12/how-popular-are-africa1-summits-among-the-continents-leaders?lang=en.

- [10] Cichocka, Beata, and Mikaela Gavas. 2021. “Europe, Take Note: A New Course for China-Africa Relations Set Out at FOCAC 2021.” Center for Global Development, December 9, 2021. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/europe-take-note-new-course-china-africa-relations-set-out-focac-2021.

- [11] Leahy, Joe, Andres Schipani, and Joseph Cotterill. 2024. “China’s Xi Jinping Courts African Leaders to Ward Off Geopolitical Rivals.” Financial Times, September 5, 2024.

- [12] 鈴木一人『資源と経済の世界地図』PHP研究所、2024年、鈴木一人. 2024. 「経済安全保障から地経学へ」『地経学ブリーフィング』No.200 https://apinitiative.org/2024/04/17/57188/

- [13] 「援助・政策取引」論に依拠し、援助提供国と援助受入国の間の政治経済のやりとりを分析した論考として代表的なものに、Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. 2009. “A Political Economy of Aid.” International Organization 63 (2): 309-340.がある。また、中国の対アフリカ融資をエコノミック・ステイトクラフトの視点から分析した論考として、Zeitz, Alexandra O. 2019. “The Financial Statecraft of Debtors: The Political Economy of External Finance in Africa.” PhD diss., University of Oxford.が挙げられる。

- [14] 大矢伸『地経学の時代―米中対立と国家・企業・価値』実業之日本社、2022年。大矢伸「国際経済と経済安全保障 ―制裁、金融、通貨を中心に」国際文化会館地経学研究所編『経済安全保障とは何か』東洋経済新報社、2024年。

- [15] 习近平在中非合作论坛北京峰会开幕式上的主旨讲话(全文)https://2024focacsummit.mfa.gov.cn/kms/202409/t20240905_11485611.htm

- [16] Hirschman, Albert O. 1945. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- [17] 猪俣哲史『グローバル・バリューチェーンの地政学』日経BP、2023年。

- [18] 同様に、頻繁に国際文書に取り入れられ、国際目標のように言及されてきた中国共産党のスローガンとして、「運命共同体(a community with shared future)」がある。

- [19] 中華人民共和国外交部「全球安全倡议概念文件(全文)」2023年2月21日。https://www.mfa.gov.cn/wjbxw_new/202302/t20230221_11028322.shtml

- [20] 江藤名保子「日中関係の展望」『中国で何が起きているのか』(18)、日本記者クラブ、2024年9月12日、https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ofd-Bj2JsvA&t=1s(2024年9月18日閲覧)

- [21] Brown, William, and Sophie Harman, eds. 2013. African Agency in International Politics. 1st ed. London: Routledge. Mohan, Giles, and Ben Lampert. 2013. “Negotiating China: Reinserting African Agency into China–Africa Relations.” African Affairs 112 (446): 92-110.

- [22] Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. 2016. “Competition and Collaboration in Aid-for-Policy Deals.” International Studies Quarterly 60 (3): 413-426.は、実証分析により、ある途上国に複数の援助国が援助を提供する場合、競争メカニズムが働き、それにより、単数の援助国が援助を提供するよりも、「援助・政策取引」において、途上国側から望ましい政策を引き出すため、より多くの援助を提供せざるを得ないことを示した。

- [23] Soulé, Folashadé. 2020. “‘Africa+1’ Summit Diplomacy and the ‘New Scramble’ Narrative: Recentering African Agency.” African Affairs 119 (477): 633–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adaa015. Amare, T. and Vines, A. (2024) ‘China–Africa summit: Why the continent has more options than ever’, Chatham House, 13 September. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/09/china-africa-summit-why-continent-has-more-options-ever (Accessed: 24 September 2024).

- [24] 神保謙「多極化世界への準備ができない米国:米国と世界の潮流のミスマッチをどう克服するか」『地経学ブリーフィング』No.221、アジア・パシフィック・イニシアティブ、2024年9月19日、https://apinitiative.org/2024/09/19/59502/(2024年9月19日閲覧)。

- [25] Leahy, Joe, Andres Schipani, and Joseph Cotterill. 2024. “China’s Xi Jinping Courts African Leaders to Ward Off Geopolitical Rivals.” Financial Times, September 5, 2024.

- [26] 白戸圭一「転機を迎えたTICAD プロセス」『アフリカレポート』, 60, 32-38、2022年、白戸圭一「冷めたTICAD―アフリカは日本の『300億ドル拠出』に期待していない」『フォーサイト』2022年9月22日。金子七絵「TICADプロセスと日本のアフリカ開発協力」『立法と調査』第451号、2022年、66-82頁。

Senior Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow of the China Group at the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG). Doi specializes in China and the world (geoeconomic issues, such as development finance and emerging technologies), and global governance in the social development sectors, including education and health. He graduated from the University of Kitakyushu with a B.A. in International Relations (Contemporary China Studies) and a Master of Public Policy from the University of Tokyo. Doi joined the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 2008, where he worked on the implementation of the Japanese government’s foreign aid to China at the JICA Beijing Office and conducted financial investments in economic and social infrastructure, sovereign credit risk analysis and research on China’s development cooperation with the Global South at the Africa Department. In 2018, he began his doctoral studies in the Department of Education Economics at Peking University in China, where he received his PhD in Public Policy in 2022. Doi served as a senior researcher and advisor at Diinsider Co., Ltd, a China-based international development consultancy, and as an adjunct researcher at the Center for the Study of International Cooperation in Education, Waseda University, before being appointed to his current position in August 2024. His research has been published in books by international publishers, including Routledge and Springer Nature, as well as in international peer-reviewed journals such as Development Policy Review, Higher Education Research & Development, Public Health Action, and Compare. [Concurrent Positions] Adjunct Researcher, Center for the Study of International Cooperation in Education, Waseda University, Japan. (2023-Present) Visiting Lecturer, Department of International Business and Management, Kanagawa University, Japan. (2025-2026).

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09