Chapter 1 Hungary: Media Control and Disinformation

The Orbán Viktor [2] government has been steadily intensifying its grip on state-run, conservative, and independent media through legislative reform and buying ownership of these media,[3] which allows the government to more indirectly and strategically spread its own narrative including disinformation.[4] For example, the “Media Pluralism Monitor”, an annual report on European media published by the European University Institute accuses “the governing party” for having “a very strong influence over content production and editorial decision making” in both the public and private media in Hungary. [5] The European Commission’s “2023 Rule of Law Report” also expresses concern over the functional, editorial, and financial independence of the Hungarian media.[6]

Furthermore, in 2021, a report commissioned by the European Parliament argued that there has been evidence to suggest that the spread of disinformation in Hungary originate from “government-controlled media”.[7] This point is echoed in a 2020 report by the European Digital Media Observatory which argues that the Hungarian government is actively spreading disinformation, and the EU DisinfoLab’s report points to the Hungarian government as one of the sources of disinformation in Hungary. [8] Even while preparations are underway in the EU to enact and implement a comprehensive set of regulations against online platforms, [9] Hungarian anti-disinformation policy is far from functional. [10] In Hungary, disinformation is present even within articles from traditional media outlets, and such disinformation is actively spread by politicians in the central government.

Democratic Backsliding: Increased Control over Information Sources Through Media Acquisitions

This chapter discusses the issues of democratic backsliding and the proliferation of disinformation under the Orbán regime in Hungary. The first section reviews the historical process of state influence over the media amidst the erosion of democracy by the Orbán government. The second section introduces disinformation originating from Russia,[11] and disinformation and conspiracy theories that originate from Hungary that are spread by government officials and state- controlled media. This chapter presents a unique disinformation phenomenon in Hungary which is the “import” and “export” of disinformation. The third section provides an overview of the negative consequences of such disinformation. The European refugee crisis and the Russia-Ukraine war are presented as examples of large-scale disinformation campaigns in Hungary.[12]

“Between 2010 and 2020, only four anti- government media outlets disappeared [and the total] number had risen to 48 [from 33] by 2020”[13]

This quote from Bíró András, a researcher at the pro-government think tank, XXI. Század Intézet, attempts to portray the current state of media freedom in Hungary as being free and balanced. Emphasizing the point, Prime Minister Orbán himself once asserted in 2015 that “if you look at the Internet, you can easily see that there is freedom of the press”.[14] Yet, Hungary faces a major constraint to its media freedom. The following section will analyze the influence of the Hungarian political party Fidesz led by Orbán, and pro-government businessmen over the state-controlled, conservative, and independent media.[15]

Step One: Control of the Public Media

Prime Minister Orbán won his first term as prime minister in 1998 by defeating the Socialist Party, eight years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In his first term, Orbán critiqued the media for what he called its opposition-aligned reporting, arguing that “the media is doing the work of the opposition.”[16]

In response , Orbán sought to increase his party’s influence over the media during his first term by staffing the National Radio and Television Board (ORTT), the state-run media regulatory institution, exclusively with members of his party in 1999, in contradiction to the balanced representation required under the 1996 Media Law.[17] This attempt ultimately failed as Fidesz was kicked out of power in the 2002 general election when they narrowly lost to the Socialist Party. However, Fidesz solidified its control over the media shortly after forming a government for a second term in 2010. The media law was revised, leading to the appointment of the director of Magyar Távirati Iroda (MTI) as the head of the newly established Media Council (NMHH) which replaced the ORTT and it now oversees all funding allocations. [18]

Step Two: Consolidation and Establishment of Conservative Media

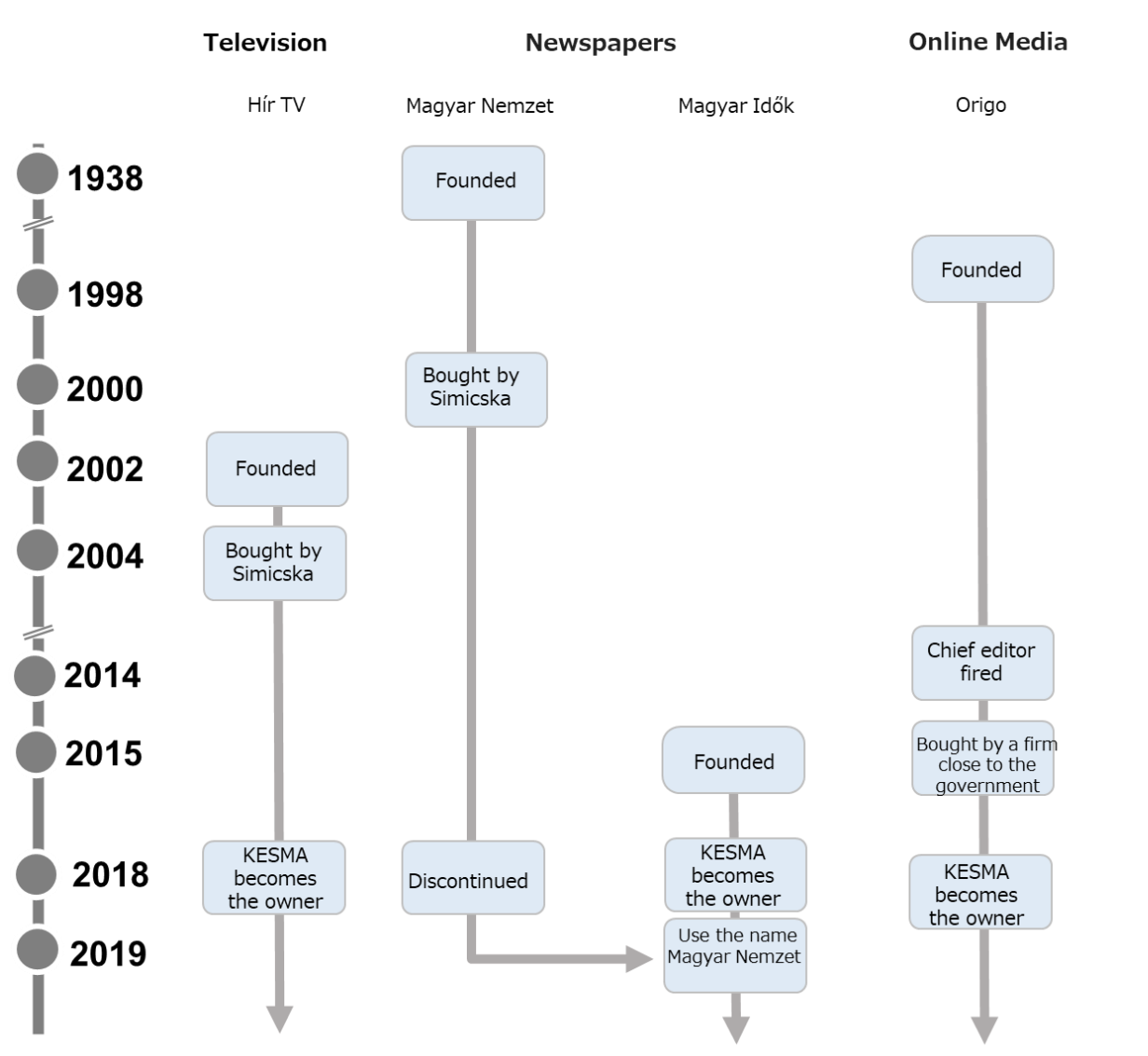

In addition to changing the Media Law, the Orbán government has used its financial power to buy out media firms. [19] The next section will discuss how the Hungarian government has been able to exert stronger control over Hír TV, a conservative outlet, as well as Origo, a formerly independent outlet.

Orbán attributed the narrow 2002 election defeat to “the concentration of media and money on the opposing candidate”, which deepened his concern of both traditional print and online media influence. [20]This led Orbán, Fidesz, and pro-government businessmen to strengthen their influence on the media through the establishment of conservative media and merging different media outlets.

Launched in late 2002, Hír TV was established as a conservative TV outlet under the leadership of Borókai Gábor, a government spokesperson during Orbán’s first term. By 2004, businessman Simicska Lajos, a key figure from Orbán’s first administration that had personal ties to Orbán having been the head of the internal revenue service of the first Orbán government as well as sharing the same dorm with Orbán at university, had acquired Hír TV. [21] This acquisition fortified Fidesz’s reliance on Hír TV, which was evident in its exclusive live coverage of substantial anti-Socialist Party government protests in 2006 and Orbán’s public speeches which they reported live on several occasions. [22] A Hungarian born journalist, Paul Lendvai argues that to strengthen Fidesz’s communication, the first Orbán administration decided to rely on the powerful conservative “media empire” created by Simicska who was personally close to Orbán. [23]

Despite the closeness between Simicska and the Orbán administration, he allowed articles critical of the government to be published. The same was true for Magyar Nemzet, a conservative daily newspaper first published back in 1938, [24] and multiple other conservative media outlets owned by Simicska. [25]

However, the close relationship between the Orbán administration and Simicska’s media enterprise began to fracture as the government sought ever-greater loyalty. [26] In the 2014 general election, Fidesz secured over two-thirds of the seats in Hungary’s unicameral national assembly with 52.73 per cent of the vote, a victory mainly thought to be secured through electoral gerrymandering. [27] The second Orbán government hinted at introducing a 5 per cent advertising tax on the media. The Hungarian media’s financial situation is fragile, and the media is often financially reliant on advertisement revenue. [28] An introduction of an advertisement tax presents considerable financial burden on the Hungarian media. [29] Simicska harshly criticized this as a “total media war” and “another attack on democracy”, [30] severely worsening the relationship between him and Orbán.

As a result, media owned by Simicska increasingly found themselves in considerable financial difficulties, presenting pressure on it as a media outlet. [31] They were labeled ‘fake news’ by Orbán and subsequently denied interviews with the government. [32]

Deprived of its political access and financial backing, Simicska’s outlets were ultimately consolidated under the Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA), established in 2018 by Orbán and the ruling Fidesz party. KESMA’s preamble to its Foundation’s Charter states that “the Hungarian written and electronic press has an indisputable role and responsibility in strengthening community cohesion and in laying the foundation for thinking about our common future”. [33] Not only Hír TV, but also Magyar Nemzet were ultimately shut down in 2018, and in the following year, Magyar Idők, a publication with strong links to Fidesz and under KESMA’s ownership, recaptured “Magyar Nemzet” as its new name. [34]

Designated as a “strategic” national asset, [35] KESMA is exempt from monopoly regulations. It now encompasses over 400 media entities, a monumental consolidation of pro-government media under a single entity. This strategic amalgamation represents a deliberate effort to homogenize media narratives, illustrating the Orbán administration’s unwavering commitment to controlling the public discourse. As Scott Griffin, the deputy director of the International Press Institute (IPI), points out,

“The bundling of pro-government media under one roof removed the risk of ‘runaway oligarchs’, and… facilitates a coordinated system of censorship and content control among the media involved”. [36]

Step Three: Pressure and Takeover of Independent Media

Takeovers to assure government control extended to outlets that were critical of the government as well, such as Origo. Launched in 1998, Origo was once among Hungary’s most popular and well-respected online journalism platforms. [37] The Orbán administration, at the cusp of its third term in 2014, started pressuring Origo through its parent company, Magyar Telekom, concerned about its critical coverage of the government. In 2013, amid discussions on new licensing, Lázár János, Secretary of State of the Prime Minister’s Office, proposed establishing a communication line between Origo’s editors and government officials to Magyar Telekom. That fall, while not explicitly requesting a quid pro quo arrangement, Patrick Kingsley, a New York Times journalist argued that a media consulting firm close to the Orbán administration signed a contract with Origo to make suggestions about government coverage, ostensibly creating a channel for the government to influence Origo’s reporting. [38]

Nevertheless, the press team continued to scrutinize the Orbán administration under the leadership of editor-in-chief Gergő Sáling. In the same year, they also exposed high overseas travel expenses incurred by Lázár János. [39] However, the Orbán administration found such critical coverage unacceptable, and as a result, the pressure on the parent company intensified, leading to the dismissal of Sáling, on June 3, 2014. [40] After his dismissal, according to journalist Orla Barry, there has been a shift in reporting which has become more pro-government. [41] Origo was subsequently acquired in 2015 by a company under the control of two banks aligned with the Orbán administration, [42] and in 2018, it became part of KESMA (Figure 1).

Disinformation Through the Media and Its Impact: The Refugee Crisis

The Orbán government, unlike Russia and China, does not censor its media, and does not apply such heavy-handed tactics. For outlets that are more critical of the government, they are prepared to use political pressure, economic “sanctions”, and even outright takeovers. It was precisely in the backdrop of the formation of a media landscape in which only opinions favorable to the government were being reported in the mid-2010’s that the refugee crisis started in Europe.

The spring 2015 influx of refugees and migrants from the Middle East and North Africa caused significant turmoil across Europe, with Hungary becoming a crucial transit point along the so-called “Balkan route” from Serbia to Germany. The Hungarian government viewed this to be a national threat and declared a state of emergency in September of 2015. [43]

Figure 1: Major Private Media in Hungary and Its Ownership throughout the Years (Source: Author)

(Source: Author)

Amidst this influx, various conspiracy theories and disinformation [44] were floating around regarding the refugees and migrants, [45] including many so-called attacks on Orbán’s political opponents such as George Soros who became one of the targets of conspiracy and disinformation attacks from the Hungarian media under the influence of the Hungarian government. [46]

George Soros is a prominent Hungarian- American investor of Jewish background and a vigorous advocate for democracy. He founded the Central European University and the Open Society Foundations, both initially based in Hungary, and both of which were compelled to relocate due to pressure from the Orbán administration. Many right-wing politicians and media in the United States, Russia, and beyond have propagated numerous conspiracy theories against Soros. However, according to journalist Patrick Stickland, to justify their arguments and shore up their support, the Orbán administration has actively leveraged these theories to undermine Soros, who they view as a political adversary due to his criticism against the government over democratic values and human rights issues. [47]

One illustration of this tactic is the peddling of the so-called “Soros Plan”, a conspiracy theory claiming that Soros aims to transport large numbers of migrants to Europe to further his economic interests and weaken national governments. Fidesz has been conducting national polling since 2005 when they were in opposition. Questionnaires are sent by post to all Hungarian households, and respondents are given the option to answer “yes” or “no” to the questions. While the aim of this poll is to gather public opinion, in reality it can be used to promote the government’s position as well as a way to justify government decisions and as a negative campaign tool against their opponents. [48] The “Soros Plan” was put before Hungarians in a government poll conducted in 2017, and in one of the explanations to the questions posed it stated that “Soros has been working for many years to change Europe and European societies. He wants to achieve his goal with the resettlement of masses of people from different cultural backgrounds”. [49] Researchers such as Ágnes Bátory et al. have argued that the Orbán government tried to justify their view that Soros is behind the European Union’s refugee and immigration policy to the public through such questionnaires. [50]

Regarding such campaigns against Soros by the Hungarian government, then President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker stated after a European Council meeting in 2018 that “[s]ome of the prime ministers sitting around the table, they are the origin of the fake news”, following this with a direct criticism against Orbán for being one of the spreaders of disinformation. [51]

In addition to conspiracy theories like this one, there was also the spread of disinformation on Soros. For instance, in 2018, Magyar Idők reported disinformation claiming that “the European Commission and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) distributed tens of thousands of anonymous bank cards to migrants”, implicating that Soros “participated in financing this”. [52] While it is true that there are programs to provide assistance to refugees via card-based systems, including a Soros-funded MasterCard initiative since 2011 aimed at supplying necessities through pre-loaded cards before the refugee crisis, these programs are unrelated. [53] Misrepresenting these separate efforts as connected served to discredit Soros by implying that EU funds are allowing migrants to help terrorism as its title implied (“A migránsoknak kibocsátott névtelen bankkártyák a terrorizmust segítik” which translates to “Anonymous bank cards issued to migrants help terrorism”). [54] This disinformation was reportedly sourced from Nova24, a conservative Slovenian news outlet. [55] The Orbán government after expanding its influence over domestic Hungarian news outlets has been turning its focus on helping Hungarian businesses to acquire foreign media, a move that is evident in Slovenia since 2017. Schatz Péter, the pro- Orbán former director of Hungary’s Danubius Radio, has been involved in the acquisition of Nova24. [56] The Slovenian conservatives, like the Orbán government are opposed to immigration, and have forged a close relationship with them as a result.

The idea that there is a “uniform negative bias” in the international media reporting that is creating a “long-lasting and unfavourable effect on Hungary’s international reputation” has been widely adopted among Hungarian conservatives such as Fidesz. [57] Márton Dunai, a former Reuter journalist argues that the Hungarian conservatives such as Fidesz is trying to heighten their international reputation by strengthening such views to be promoted abroad. [58]

The Russia-Ukraine War: The Import and Export of Disinformation

Europe faced several significant crises in the 2020s, starting with the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in 2020, followed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Despite the Orbán government’s official stance against Russia’s illegal and unprovoked aggression, which is repeatedly declared in UN general assemblies, the European Council meetings, and Council of the European meetings, its approach has been notably cautious to avoid deliberately provoking Russia since the onset of the conflict. This caution is reflected in the coverage by Hungary’s government-aligned media, where pro-Russian narratives and disinformation are notably prevalent. [59]

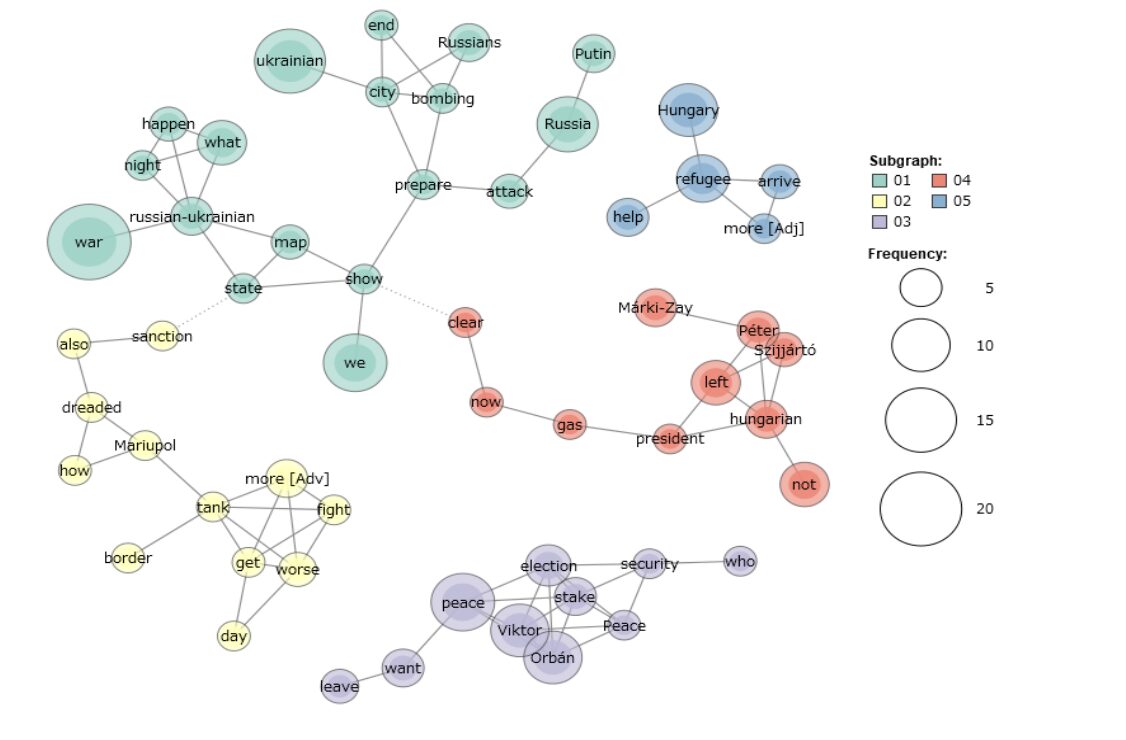

For example, an analysis of the co- occurrence network (a graphic textual analysis) of coverage from March 2022, prior to the Hungarian parliamentary elections

reveals that Origo, once known for its balanced reporting and now under KESMA since 2018, now tends to align with the Orbán administration’s narrative, often reporting phrases like “Orbán wants peace” (see Figure 2, Subgraph 3 which is in purple), indicating Origo’s transformation into a media outlet that is more aligned with the government.

Looking more closely at the themes that emerged from this analysis, it is clear that within reports from state-controlled media contain disinformation. For example, the criticism lodged by Minister of Foreign Affairs & Trade Péter Szijjártó against the prime ministerial candidate Péter Márki-Zay is being actively promoted (see Figure 2, Subgraph 4 which is in red), and contains disinformation such as “[t]he Left would send weapons and soldiers to Ukraine, thus dragging Hungary into war” or that “[t]he left would abolish the utility cost cuts”. [60]

In addition, on public television channel M1, one guest praised the actions of Russian soldiers as “professional” and stated they “calmly did their job”. This guest also compared the Zelensky’s administration to Nazi Germany and claimed that Ukraine was developing nuclear weapons, without any evidence. [61] The guest in question was Georg Spöttle, a former West German police officer and a security expert who has become a regular figure on media outlets like Hír TV and Magyar Nemzet in recent years. He was also a former analyst at a pro-government think tank, Nézőpont Intézet. The comment by Spöttle illustrates how conservative Hungarian “experts” are spreading Russian government disinformation. While not exclusive to Hungary [62] – the EUDisinfo Lab highlights that the widespread dissemination of such disinformation, especially through state-owned or government-leaning media – it is a phenomenon that is particularly prominent in Hungary. [63]

Figure 2: Ukraine Coverage by Origo from March to April 2022 elections (Source: Author)

(Source: Author)

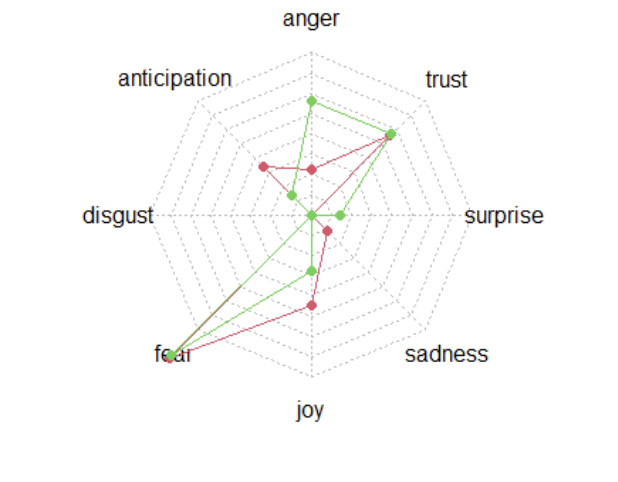

A notable aspect of disinformation in Hungary involves the “export” of disinformation to Russian media, thereby adding Hungarian-made veneer of credibility to Russian narratives. An example of this is the unfounded claim of “forced recruitment” of the Hungarian minorities in Ukraine’s western Transcarpathian region. In January 2023, the conservative media outlet Pesti Srácok (which, while not part of KESMA, supports the Orbán government) published an alleged fabricated story, falsely reporting that a significant number of Ukrainian soldiers and police officers had descended upon the Transcarpathian region, engaging in widespread forced recruitment (called “kényszersorozás” in Hungarian) of the region’s Hungarian minority population. The report was based on the unsubstantiated rumor that “the operation aimed to conscript tens of thousands from regions untouched by the war’s immediate impacts”. [64] In response to this report, Ukraine’s Espreso TV unequivocally identified it as a disinformation campaign, highlighting that the store, where Pesti Srácok claimed the alleged police and military activities occurred, does not exist in the Berehove area mentioned. They furthermore noted that the backgrounds of the individuals interviewed by Pesti Srácok were not verified, and their statements were overly emotional, placing doubt on their credibility. [65] Yet this fabricated report was also cited by multiple Hungarian media such as Magyar Nemzet, Origo, and the state-run media outlet M1, further sensationalizing fear and anger among the Hungarian public [66] (see Figure 3).

Furthermore, Russian media (such as TASS) have echoed the report, replicating the narrative set forth by Hungarian outlets. Dorka Takácsy, a Marcin Król Fellow at the Warsaw-based platform Visegrad Insight, commented on the dissemination of the Pesti Srácok article, noting its impact and the broader implications for media representation and how disinformation can spread.

Figure 3: Emotion analysis of headlines (data collected between January 22, 2023, when the “forced recruitment” theory was first reported, to February 4, 2023) of Mager Nemzet (red) and Origo (green). [67] (Source: Author)

(Source: Author)

This fabricated story was then picked up by the leading Russian news agency TASS. Interestingly, they took over the novel wording as well, using “принудительный призыв” (“forceful conscription”) instead of мобилизация (mobilisation) in Russian. From TASS, this news was republished by many Russian news portals, including the largest ones. Hence, Ukraine was presented to Russian readers as an aggressor and emphasised that ethnic Hungarians, not just ethnic Russians, are victims of their repression (as popular Russian disinformation narratives claim). [68]

The coverage of the Pesti Srácok article by the TASS news agency had a notable impact, with Russia Today (now RT) reporting on it on January 27, 2023, [69] and Infobrics, the official BRICS information website, describing the “forced recruitment” theory on February 2, 2023. [70] It was also observed that Rossiya Segodnya, another Russian state- owned entity that oversees the Novosti and Sputnik news agencies, contemplated hiring a

Hungarian-speaking editor in the fall of 2022, [71] indicating a significant likelihood that disinformation originating from Hungary could be utilized by Russian outlets in the future.

The Negative Impact of Disinformation These two examples of disinformation campaigns – the refugee crisis and the war in Ukraine – reflect the significant impact of disinformation in Hungary in two important ways.

One, disinformation in Hungary has helped diminish public trust in the media and contributed to worsening political polarization. In 2016, public trust towards the media declined to 31 percent, and it continued to decline under the Orbán administration so that by 2022, it sunk to 25 percent, [72] even more than the other two case studies considered in the report, the United States [73] (32 percent) and the United Kingdom [74] (33 percent). At the same time, among voters who support the Orbán administration (or to be more precise, those who lean conservative), a slightly higher proportion trust the media at 33 percent. [75] Furthermore, in regards to political polarization, only a quarter of Hungarians agreed with the statement that “politics is ultimately a fight between good and evil” in 2014, but by 2022 this figure increased to 39 percent, strongly suggesting a broader pull towards polarization. [76]

Additionally, the spread of propaganda favorable to Russia and outright disinformation during the Russia-Ukraine war led to greater support of authoritarian regimes such as Russia, while at the same time reducing support for democratic western states such as the United States and EU member states that tried to uphold the rule of law. [77] Fidesz, which prioritizes relations with Russia over the United States, succeeded in increasing their support from 39 percent to 55 percent, while opposition parties which took the opposite view saw their support decline from 39 percent to 24 percent in 2022. [78]

Conclusion

There has been a gradual but steady tightening of media freedom in Hungary since the Orbán administration first assumed office in1998. The Orbán administration intensified its control at the onset of their return to power in 2010, and recent years have witnessed attempts to extend influence over media both domestically and internationally. These trends continue, and the spread of pro-government narratives that can be viewed as disinformation by the Hungarian government and government- leaning media regarding immigrants and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been made an issue in the European parliamentary election 2024. [79]

This presents an important warning to countries such as Japan to not blindly trust reporting by foreign media. In countries that experience democratic backsliding, there is no guarantee that formerly independent media have maintained their independence, and there may also be nominally independent media that are subject to government control. When disinformation is disseminated from multiple sources, as in the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the example of Hungary strengthens the need to account for the political and economic context, as well as the degree of independence of the media.

This chapter has provided an overview of disinformation in Hungary, a country that faces democratic backsliding. The next chapters will explore the potential impact and responses to disinformation in democracies at risk.

Footnote

- [1] Vanessa A. Boese et al., Autocratization Changing Nature? Democracy Report 2022 (Göteborg: Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2022), https://v-dem.net/media/publications/dr_2022.pdf.

- [2] Konard Bleyer-Simon, Gabor Polyak, and Agnes Urban, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era – Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia & Turkey in the year 2022 – Country report – Hungary (Florence: European University Institute, 2023), 26, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75725/Hungary_results_mpm_2023_cmpf.pdf.

- [3] European Commission, 2023 Rule of Law Report Country Chapter on the rule of law situation in Hungary (Brussels: European Commission, 2023), https://commission.europa.eu/publications/2023-rule-law-report-communication-and-country-chapters_en.

- [4] Judit Bayer et al., Disinformation and propaganda: impact on the functioning of the rule of law and democratic processes in the EU and its Member States (Brussels: European Parliament, April 2021), 46, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/653633/EXPO_STU(2021)653633_EN.pdf.

- [5] Bleyer-Simon et al., Monitoring media pluralism.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] Bayer et al., Disinformation and propaganda, 46.

- [8] European Digital Media Observatory, Policies to tackle disinformation in EU member states – part 2 (Florence: Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, European University Institute, 15), https://edmo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Policies-to-tackle-disinformation-in-EU-member-states-%E2%80%93-Part-II.pdf; Konrad Bleyer-Simon, The disinformation landscape in Hungary (Brussels: EU DisinfoLab, 2023), https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/disinformation-landscape-in-hungary/.

- [9] For further information on the EU’s regulatory trends on disinformation for various social media providers, please refer to Takashi Kawaguchi, 民主主義国家とデジタルプラットフォーム規制 [Democracies and online platform regulation], Geoeconomic Briefing, https://instituteofgeoeconomics.org/research/2024041057049/.

- [10] European Digital Media Observatory, Policies to tackle disinformation in EU member states – part 1 (Florence: Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, European University Institute), https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/74325/Policies-to-tackle-disinformation-in-EU-member-states-during-elections-Report.pdf?sequence=1%26isAllowed=y.

- [11] For a more general explanation of Russian disinformation, please refer to: Global Engagement Center, Pillars of Russia’s Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State, 2023), https://www.state.gov/russias-pillars-of-disinformation-and-propaganda-report/.

- [12] Political Capital, “The Building of Hungarian Political Influence – The Orbán Regime’s Efforts to Export Illiberalism,” Political Capital, December 20, 2022, https://politicalcapital.hu/news.php?article_read=1&article_id=3311.

- [13] András Bíró, “The Rule of Law Witch Hunt against Hungary and Poland Should Stop,” Hungarian Conservatism 2, no. 3 (2022): 60-67, 63, https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/33541164.

- [14] Mainichi Shimbun, “Hungary, fighter’s ‘change’ / 4 Government accelerates media domination,” Mainichi Shimbun Online, December 28, 2019, https://mainichi.jp/articles/20191228/ddm/007/030/093000c.

- [15] Eileen Culloty and Jane Suiter, “Media control and post-truth communication,” in Routledge Handbook of Illiberalism, ed. András Sajó et. al. (New York: Routledge, 2021), 365-383.

- [16] Daniel Langenkamp, “Hungary’s media war raises eyebrows in West,” The Christian Science Monitor, April 20, 2000, https://www.csmonitor.com/2000/0420/p11s2.html.

- [17] Ibid.

- [18] Amy Brouillette et al. eds., Hungarian Media Laws in Europe (Vienna: Center for Media and Communication Studies, Central European University, 2012), https://www.eui.eu/Documents/General/DebatingtheHungarianConstitution/HungarianMediaLawsinEurope.pdf; For more information on the Media Council and the ad tax discussed below, see Gábor Polyák, “Media in Hungary: Three Pillars of an Illiberal Democracy,” in Public Service Broadcasting and Media Systems in Troubled European Democracies, eds. Eva Połońska and Charlie Beckett (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 279-303, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02710-0_13.

- [19] Culloty and Suiter, “Media control and post-truth communication.”

- [20] Zsuzsanna Szelényi, Tainted Democracy: Viktor Orbán and the Subversion of Hungary (London: Hurst Publishers, 2022, Kindle), p. 27; Attila Bátorfy,

“How did the Orbán-Simicska media empire function,” Kreatív Online, April 07, 2015, https://kreativ.hu/cikk/how_did_the_orban_simicska_media_empire_function. - [21] Csatári Flóra Dóra and Fábián Tamás, “The shredding of the free press in Hungary,” Telex, November 25, 2021, https://telex.hu/english/2021/11/25/the-shredding-of-the-free-press-in-hungary.

- [22] Anna Szilágyi and András Bozóki, “Playing it again in post-communism: the revolutionary rhetoric of Viktor Orbán in Hungary,” Advances in the History of Rhetoric 18, no. sup1 (April 2015): S153-S166, https://doi.org/10.1080/15362426.2015.1010872.

- [23] Rényi Pál Dániel, “The Rise and Fall of the Man Who Created Viktor Orbán’s System,” 444.hu, April 22, 2019, https://444.hu/tldr/2019/04/22/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-man-who-created-viktor-orbans-system.

- [24] Magyar Nemzet was bought by Simicska in 2000.

- [25] Rényi Pál Dániel, “The Rise and Fall of the Man Who Created Viktor Orbán’s System,” 444.hu, April 22, 2019, https://444.hu/tldr/2019/04/22/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-man-who-created-viktor-orbans-system.

- [26] HVG, “Az út a ‘Simicska a legokosabb’-tól az ‘Orbán egy geci’-ig [The road from “Simicska is the smartest” to “Orbán is a dick”], HVG, February 04, 2015, https://hvg.hu/itthon/20150206_Igy_juttottunk_el_a_Simicska_a_legokosabb.

- [27] Kim Lane Scheppele, “How Viktor Orbán Wins,” Journal of Democracy 33, no. 3 (July 2022): 45-61, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2022.0039.

- [28] Transparency International Magyarország, Korrupciós kockázatok Magyarországon 2011 (Budapest: Transparency International Magyarország, 2012), https://transparency.hu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Korrupci%C3%B3s-kock%C3%A1zatok-Magyarorsz%C3%A1gon-2011-Nemzeti-Integrit%C3%A1s-Tanulm%C3%A1ny.pdf.

- [29] Népszavá, “Simicska: akkor totális háború lesz [Simicska: then it will be total war],” Népszavá, February 05, 2015, https://nepszava.hu/1047595_simicska-akkor-totalis-haboru-lesz.

- [30] Ibid.

- [31] HVG, “Az út a ‘Simicska a legokosabb’-tól az ‘Orbán egy geci’-ig [The road from “Simicska is the smartest” to “Orbán is a dick”],” HVG, February 04, 2015, https://hvg.hu/itthon/20150206_Igy_juttottunk_el_a_Simicska_a_legokosabb.

- [32] Hír TV, “Trumpi diskurzus: Orbán Viktor szerint fake newst gyárt a Hír TV [Trump discourse: According to Viktor Orbán, Hír TV produces fake news],”

Hír TV, March 10, 2018, https://hirtv.hu/ahirtvhirei_adattar/trumpi-diskurzus-orban-viktor-szerint-fake-newst-gyart-a-hir-tv-2452743. - [33] “Az Alapítvány Alapító okiratának Preambuluma [Preamble to the Foundation’s Articles of Association],” Közép Európai Sajtó és Média Alapítvány, last accessed October 24, 2024, https://cepmf.hu/.

- [34] Budapest Business Journal, “Government recaptures Magyar Nemzet brand,” Budapest Business Journal, February 06, 2019, https://bbj.hu/budapest/culture/history/government-recaptures-magyar-nemzet-brand/.

- [35] Scott Griffen, “Hungary: a lesson in media control,” British Journalism Review 31, no. 1 (February 2020): 57-62, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956474820910071.

- [36] Ibid, 59.

- [37] Origo’s role as a news journalism outlet is evidenced by the fact that former Origo editor-in-chief Shirling launched Direkt36, a website dedicated to news journalism, with her former colleagues in 2015. For more information, see Caroline Lees, “Hungary: Investigative Journalism Start-up,” European Journalism Observatory, January 09, 2015,

https://en.ejo.ch/media-politics/hungary-investigative-journalism-startup. - [38] Patrick Kingsley and Benjamin Novak, “The Website That Shows How a Free Press Can Die,” New York Times, November 23, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/24/world/europe/hungary-viktor-orban-media.html.

- [39] Lydia Gall, “Hungary’s Insidious Media Clampdown,” Human Rights Watch, June 13, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/06/13/hungarys-insidious-media-clampdown.

- [40] Orla Barry, “As Orbán rises, Hungary’s free press falls,” The World, February 12, 2019, https://theworld.org/stories/2019/02/12/placeholder-hungary-day-2.

- [41] Magyar Telekom was subject to a “crisis tax” imposed on the telecommunications (and retail and energy) industry in 2010 as a measure of financial recovery from the Great Recession.

- [42] This has been renewed every six months since 2016, even as the influx has subsided almost nine years later.

- [43] Judit Szakács and Éva Bognár, The impact of disinformation campaigns about migrants and minority groups in the EU (Brussels: European Parliament, June 2021), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2021/653641/EXPO_IDA(2021)653641_EN.pdf.

- [44] Refugees and immigrants have been driven into Europe due to turmoil in Central and North Africa, notably the Syrian civil war sparked by the Arab Spring, Germany’s welcoming policy towards refugees, and the decisions by southern European countries outside the Schengen Agreement to allow refugees and immigrants to transit through their territories to pass to northern EU countries and alleviate their own burdens. See Inui Endo, “The European Refugee Crisis,” in Europe Complex Crisis: Anguished EU, Shaken World (Tokyo: Chuko Shinsho, 2016).

- [45] Patrick Strickland, “What’s behind Hungary’s campaign against George Soros?” Al Jazeera, November 22, 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/22/whats-behind-hungarys-campaign-against-george-soros; Peter Plenta, “Conspiracy theories as a political instrument: utilization of anti-Soros narratives in Central Europe,”

Contemporary Politics 26, no.5 (2020), 512-530, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2020.1781332. - [46] Ibid.

- [47] Ákos Bocskor, “Anti-Immigration Discourses in Hungary during the ‘Crisis’ Year: The Orbán Government’s ‘National Consultation’ Campaign of 2015,” Sociology 52, no.3 (2018), 551-568, https://doi.org/10.1177/003803851876208; Daniel Oross and Paul Tap, “Using Deliberation for Partisan Purposes: Evidence from the Hungarian National Consultation,” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 34, no.5 (2021), 803–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2021.1995335.

- [48] Nagy Bálint, “They are calling it a consultation, but the questions are worded to get the answers they want,” Telex, November 30, 2023, https://telex.hu/english/2023/11/30/they-are-calling-it-a-consultation-but-the-questions-are-worded-to-get-the-answer-they-want.

- [49] “Here’s the questionnaire that allows the people to have their say on the Soros Plan,” About Hungary, September 29, 2017, https://abouthungary.hu/news-in-brief/national-consultation-on-the-soros-plan.

- [50] Ágnes Bátory, “(e-)Participation and propaganda: The mix of old and new technology in Hungarian national consultations,” in Engaging Citizens in Policy Making, eds. Tiina Randma-Liiv and Veiko Lember (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2024), 56–70, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02710-0_13.

- [51] Reuters, “EU’s Juncker takes aim at Hungary’s Orban over fake news,” Reuters, December 15, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/eus-juncker-takes-aim-at-hungarys-orban-over-fake-news-idUSKBN1OD1QM.

- [52] Magyar Idők, “Kósa Lajos: A migránsoknak kibocsátott névtelen bankkártyák a terrorizmust segítik [Lajos Kósa: Anonymous bank cards issued to migrants help terrorism],”

Magyar Idők, November 06, 2018, https://www.magyaridok.hu/belfold/kosa-lajos-fel-kell-lepni-a-migransoknak-kibocsatott-nevtelen-bankkartyak-ellen-3644153/. - [53] Arturo Garcia, “Is George Soros Funding U.N.-Distributed Debit Cards to Refugees?” Snopes, November 6, 2018, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/soros-refugee-debit-cards/; Gene Emery, “Claim that George Soros is giving migrants debit cards has no collateral,” Politifact, November 13, 2018, https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2018/nov/13/blog-posting/claim-george-soros-giving-migrants-debit-cards-has/.

- [54] Magyar Idők, “Kósa Lajos.”

- [55] Bence Horváth, “Habony szlovén lapjából indult az összeesküvés-elmélet, amit ma már tényként mondott vissza Kósa Lajos [The conspiracy theory started from Habony’s Slovenian paper, which Lajos Kósa has now refuted as fact],” 444.hu, November 07, 2018, https://444.hu/2018/11/07/habony-szloven-lapjabol-indult-az-osszeeskuves-elmelet-amit-ma-mar-tenykent-mondott-vissza-kosa-lajos.

- [56] Blanka Zöldi et al., “Orbán’s media machine in the Balkans investigated for suspicious transactions,” Direkt 36, February 28, 2020, https://www.direkt36.hu/en/egymilliardot-pumpaltak-at-az-orbanek-altal-epitett-balkani-mediaba-gruevszki-ellenfelei-vizsgalni-kezdtek-a-gyanus-penzmozgast/.

- [57] Lili Zemplényi, “International Media Bias Damages Hungary’s Reputation,” Hungarian Conservative, October 12, 2022, https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/international-media-bias-damages-hungarys-reputation/.

- [58] Marton Dunai, “Hungarians start European news agency with pro-Orban content,” Reuters, April 10, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-media-news-agency/hungarians-start-european-news-agency-with-pro-orban-content-idUSKCN1RL15X/.

- [59] Yusuke Ishikawa, “The Victory of ‘Putin in Hungary’: The Era of U.S.-China ‘Competition for Inclusion’ over ‘Heretics’ Begins,” Foresight, April 15, 2022, https://www.fsight.jp/articles/-/48793.

- [60] Political Capital, “Disinformation in the election campaign – Hungary 2022,” Political Capital, May 10, 2022, https://politicalcapital.hu/news.php?article_read=1&article_id=3004.

- [61] Dániel Pál Rényi, “Kezdődik az elmebaj a közmédiában: Zelenszkij mint Hitler, higgadt oroszok, ukrán világháborús fenyegetés [The madness begins in the public media: Zelensky like Hitler, calm Russians, the threat of a world war in Ukraine],” 444.hu, February 25, 2022, https://444.hu/2022/02/25/kezdodik-az-elmebaj-a-kozmediaban-zelenszkij-mint-hitler-higgadt-oroszok-ukran-vilaghaborus-fenyegetes.

- [62] Zalán Zubor, “Invasion of Ukraine: Russian propaganda claims appear in Hungarian state media,” Atlatszo, February 28, 2022, https://english.atlatszo.hu/2022/02/28/invasion-of-ukraine-russian-propaganda-claims-appear-in-hungarian-state-media/.

- [63] Takashi Hirano, “Japanese ‘Experts’ Disseminate Russian Propaganda,” JBpress, February 05, 2022, https://jbpress.ismedia.jp/articles/-/68729.

- [64] Konrad Bleyer-Simon and Péter Krekó, The disinformation landscape in Hungary (Brussels: EU DisinfoLab, 2023), https://www.disinfo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/20230521_HU_DisinfoFS.pdf.

- [65] Füssy Angéla, “Ha ez így megy tovább, tényleg nem marad magyar Kárpátalján” – Füssy Angéla helyszíni riportja a brutális kényszersorozásokról és elnyomásról [“If this continues like this, Hungarians really won’t stay in Subcarpathia” – Angéla Füssy’s on-the-spot report on the brutal conscription and repression],” Pesti Srácok, January 22, 2022, https://pestisracok.hu/ha-ez-egy-megy-tovabb-tenyleg-nem-marad-magyar-karpataljan-fussy-angela-helyszini-riportja-a-brutalis-kenyszersorozasokrol-es-elnyomasrol/.

- [66] Espreso TV, “Hungary’s disinformation campaign plays into Kremlin’s hands in its war on Ukraine,” Espreso TV, February 02, 2023, https://global.espreso.tv/hungarys-disinformation-campaign-plays-into-kremlins-hands-in-its-war-on-ukraine.

- [67] Magyar Nemzet, “Kényszersorozások és magyarellenesség Kárpátalján [Forced conscription and anti-Hungarianism in Transcarpathia],” Magyar Nemzet, January 22, 2023, https://magyarnemzet.hu/kulfold/2023/01/kenyszersorozasok-es-magyarellenesseg-karpataljan.

- [68] In addition to analyzing the headlines, I also analyzed the text of articles that focused on the “forced recruitment” theory, but the trend of spreading the story in a way that emphasized fear was unchanged.

- [69] The brackets are as it appears on the original source. Dorka Takacsy, “Hungarian Disinformation in Russia” – Füssy Angéla helyszíni riportja a brutális kényszersorozásokról és elnyomásról [Hungarian Disinformation in Russia: How Moscow utilizes tropes from Budapest to villainize Ukraine],” Visegrad Insight, May 03, 2023, https://visegradinsight.eu/hungarian-disinformation-in-russia/.

- [70] Russian Today, “EU state slams Kiev over ‘brutal’ military draft from ethnic minority,” RT, January 27, 2023, https://www.rt.com/news/570553-ukraine-mobilization-hungarian-minority/.

- [71] Ahmed Adel, “Ukraine forcibly mobilizes citizens as Russian offensive looms and casualties mount,” Infobrics, February 03, 2023, https://infobrics.org/post/37654.

- [72] Dorka Takacsy, “Illiberal Disinformation is No One-Way Street: Russian and Hungarian Domestic Propaganda at Each Other’s Service,” AuthLib, May 04, 2023, https://www.authlib.eu/illiberal-disinformation-russian-hungarian-domestic-propaganda/.

- [73] Judit Szakács, and Éva Bognar, “Hungary – Digital News Report 2023,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, June 14, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/hungary.

- [74] Joy Jenkins and Lucas Graves, “United States,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, June 14, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/united-states.

- [75] Nic Newman, “United Kingdom,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, June 14, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/united-kingdom.

- [76] Zea Szebeni, Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti, Jan-Erik Lönnqvist, and Zsolt Péter Szabó. “The price of (dis)trust – profiling believers of (dis)information in the Hungarian context,”

Social Influence 18, no. 1 (2023): 2279662, https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2023.2279662. - [77] Péter Krekó, “The Birth of an Illiberal Informational Autocracy in Europe: A Case Study on Hungary,” Journal of Illiberalism Studies 2, no. 1 (2022): 55-72, https://doi.org/10.53483/WCJW3538.

- [78] Richárd Demény, Ráchel Surányi, Péter Krekó, Disinformation blitz during the Hungarian EP election campaign (Budapest: Political Capital, 2024), https://politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/HDMO_WP4_PC_Tanulmany_5_240731.pdf.

(Photo Credit: Shutterstock)

A dangerous confluence: The intertwined crises of disinformation and democracies: Contents

Introduction

The Definition and Purpose of Disinformation / Democratic Backsliding / Why Should We Care About Disinformation in an Era of Democratic Crisis? / Three Risks of the Spread of Disinformation and Democratic Backsliding / Report Structure

Chapter 1 Hungary: Media Control and Disinformation

Democratic Backsliding: Increased Control over Information Sources Through Media Acquisitions / Disinformation Through the Media and Its Impact: The Refugee Crisis / The Russia-Ukraine War: The Import and Export of Disinformation / The Negative Impact of Disinformation

Chapter 2 Disinformation in the United States: When Distrust Trumps Facts

The Early Years of American Disinformation: / The American Context: Distrust, Past and Present / The Challenge for Newsrooms / Managing Disinformation Through the Spreader & Consumer

Chapter 3 The Engagement Trap and Disinformation in the United Kingdom

Dragging Their Feet: Initial Slow Response to the Disinformation Threat / The Engagement Trap / A New Level of Threat to Democracy / Combatting Disinformation

Conclusion: Disinformation in Japan and How to Deal with It

Disinformation During Elections and Natural Disasters in Japan / Disinformation Policies During Crises: The 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election as Case Study / Disinformation During Crises: The Noto Peninsula Earthquake and Typhoon Jebi / Policy Recommendations

Disclaimer: Please note that the contents and opinions expressed in this report are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the International House of Japan or the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG), to which the authors belong. Unauthorized reproduction or reprinting of the article is prohibited.

Research Fellow,

Digital Communications Officer

Yusuke Ishikawa is Research Fellow and Digital Communications Officer at Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG). His research focuses on European comparative politics, democratic backsliding, and anti-corruption. He also serves as External Contributor for Transparency International’s Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, as Associate Research Fellow at the EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, and as Part-time Lecturer in European Affairs at the Department of Economics and Business Management, Saitama Gakuen University. Prior to his current roles, Research Associate at IOG and API, contributing to its translation project of Critical Review of the Abe Administration into English and Chinese. Previously, he has worked as Research Assistant for API's CPTPP program and interned with its Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Abe Administration projects. His other experience includes serving as a visiting research fellow at EUEOPEUM Institute, a full-time research intern at Transparency International Hungary, and as a part-time consultant with Transparency International Defence & Security in the UK. His publications include "NGOs, Advocacy, and Anti-Corruption" (In Routledge Handbook of Anti-Corruption Research and Practice, 2025) and A Dangerous Confluence: The Intertwined Crises of Disinformation and Democracies (Institute of Geoeconomics, 2024). He has been featured in national and international media outlets including Japan Times, NHK, TV Asahi, Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), Handelsblatt, Expresso, and E-International Relations (E-IR). He received his BA in Political Science from Meiji University, MA in Corruption and Governance (with Distinction) from the University of Sussex, and another MA in Political Science from Central European University. During his BA and MAs, he also acquired teacher’s licenses in social studies in secondary education and a TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Language) certificate. [Concurrent Positions] Associate Research Fellow, EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, Czechia External Contributor Consultant, Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, Transparency International Secretariat (TI-S), Germany Part-time Lecturer, Department of Economics and Business Management, Saitama Gakuen University, Japan

View Profile-

Analysis: Ready for a (Tariff) Refund?2025.12.24

Analysis: Ready for a (Tariff) Refund?2025.12.24 -

China, Rare Earths and ‘Weaponized Interdependence’2025.12.23

China, Rare Earths and ‘Weaponized Interdependence’2025.12.23 -

Are Firms Ready for Economic Security? Insights from Japan and the Netherlands2025.12.22

Are Firms Ready for Economic Security? Insights from Japan and the Netherlands2025.12.22 -

Is China Guardian of the ‘Postwar International Order’?2025.12.17

Is China Guardian of the ‘Postwar International Order’?2025.12.17 -

Japan-India Defense in a Fragmenting Indo-Pacific2025.12.10

Japan-India Defense in a Fragmenting Indo-Pacific2025.12.10

The “Economic Security is National Security” Strategy2025.12.09

The “Economic Security is National Security” Strategy2025.12.09 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 Event Report: The Trump Tariffs and Their Impact on the Japanese Economy2025.11.25

Event Report: The Trump Tariffs and Their Impact on the Japanese Economy2025.11.25 The Real Significance of Trump’s Asia Trip2025.11.14

The Real Significance of Trump’s Asia Trip2025.11.14 Trump’s Tariffs Might Be Here to Stay – No Matter Who’s in Power2025.11.28

Trump’s Tariffs Might Be Here to Stay – No Matter Who’s in Power2025.11.28