How Japan is building on U.S. policy for economic security

The law is made up of four pillars: strengthening supply chains for critical materials; ensuring the security of core infrastructure; promoting the development of key advanced technologies; and keeping patents on sensitive technologies that could be used for military purposes undisclosed.

The government had been implementing economic security-related policies under the framework of the security export control system based on the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law.

The framework, which originated from export controls against Communist countries centering on the Soviet Union during the Cold War era, is designed to prevent cargo containing high-performance tools and technologies from industrialized nations falling into the hands of terrorists or countries of concern that are involved in the development and production of weapons of mass destruction.

Moreover, Japan, as a major trading nation, has promoted public-private cooperation to secure a stable supply of energy sources such as oil and natural gas and mineral resources such as iron, steel, coal and rare metals, as well as other materials and food.

The country’s efforts included strengthening the free trade system and market access to secure its share, diversifying sources of supply, conducting independent development and boosting reserves, all of which had been implemented at the same time.

However, today’s geoeconomic macro trends are showing structural changes that do not allow Japan to maintain its industrial competitiveness and security only through existing policies.

The biggest change is the rise of emerging countries centering on China backed by state capitalism.

In such emerging countries, state-run companies and flagship firms strongly influenced by the state are achieving exponential growth in such sectors as energy resources, finance, information technology and telecommunications.

Many such countries have set up sovereign wealth funds using surplus reserves, intervened in financial markets without hesitation and pushed state-run firms to make strategic investments abroad.

Such state capitalism increasingly conflicted with the liberal economic order promoted by major industrialized countries.

The next key point is the fact that the global economy is seeing growing technological competition and division.

It is said that the key to creating a next-generation industry is to fuse the digital and physical worlds — through data accumulation of human movements, large-scale high-speed communication and artificial intelligence — and transform the concepts of production, labor, services and daily lives.

The problem is that technologies that serve as the platform of such transformation are increasingly fragmented in the world.

Particularly, the United States and China are experiencing fierce competition in the areas of calculation and mass data processing hardware, IT infrastructure, electronic transaction services and in the development of emerging technologies.

Such technological foundations have a great impact on the fields of life science, full automation technologies and the development of next-generation weapons.

Even more importantly, there have been more cases of countries taking advantage of the possession of sensitive technologies or supply chains to conduct coercive diplomacy — what political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman have called “weaponized interdependence.”

Such cases include China’s restriction of rare earths exports to Japan following Tokyo’s arrest of the captain of a Chinese fishing boat that collided with Japan Coast Guard vessels near the Senkaku Islands in 2010, and Beijing imposing anti-dumping duties on Australian wine in 2021.

Addressing a meeting of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission in April 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping said, “We must tighten international production chains’ dependence on China, forming a powerful countermeasure and deterrent capability against foreigners who would artificially cut off supply (to China).” This is a typical example of weaponized interdependence.

The more asymmetric the interdependence with China is — meaning the more a country is unilaterally dependent on China — the more likely it is for the country to fall prey to Beijing’s coercive diplomacy.

This is how the rise of state capitalism in the international economic order, technological competition and division, and weaponized interdependence became challenges in geoeconomic macro trends that we have to face.

U.S. economic security

The U.S. government has been the first to work comprehensively with such changes in geoeconomic macro trends.

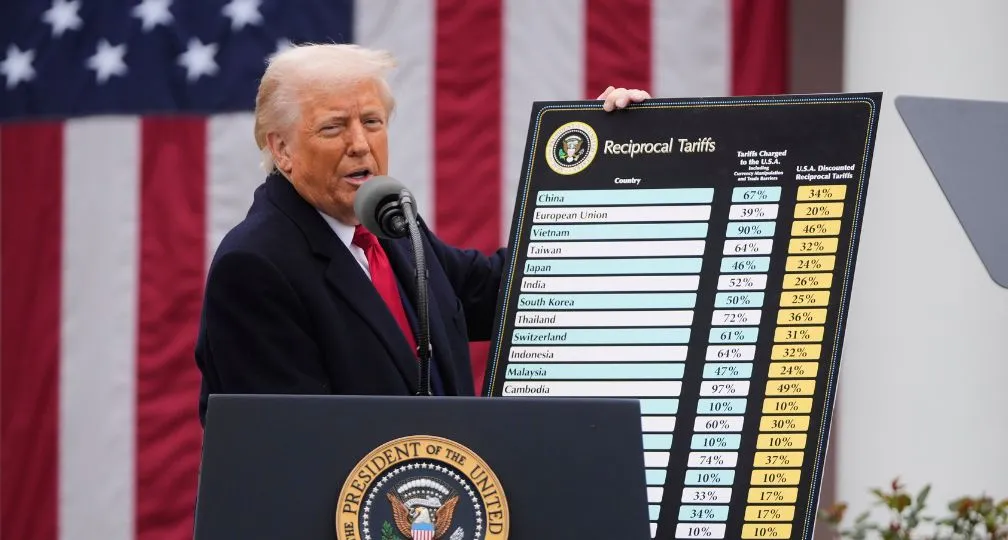

In 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration said in the National Security Strategy that “economic security is national security.”

“We welcome all economic relationships rooted in fairness, reciprocity, and faithful adherence to the rules,” the strategy document said. “But the United States will no longer turn a blind eye to violations, cheating, or economic aggression.”

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for the 2019 fiscal year that followed listed comprehensive policies on investments by foreign firms, strengthening control on China-bound exports, restrictions on federal procurements, promotion of development of advanced technologies and control on the outflow of technologies.

In August 2018, U.S. Congress enacted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act, which strengthens the authority of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to review certain transactions involving foreign investment.

The law broadens the scope of transactions subject to CFIUS review to prevent foreign firms’ involvement in investments on critical technologies and key infrastructure, as well as their exploitation of sensitive personal data.

The U.S. also introduced the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) in 2018 to restrict exports of 14 emerging and foundational technologies that can potentially be used for civilian and military purposes. These include biotechnology; artificial intelligence and machine learning technology; position, navigation and timing technology; microprocessor technology; advanced computing technology; data analytics technology; and quantum information and sensing technology.

The Export Administration Regulations (EAR) under the ECRA contain the “entity list” — a list of names of foreign people or entities engaging in activities that are contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.

Those on the list, determined by the end-user review committee composed of representatives of U.S. departments and agencies, are subject to specific license requirements for the export of specified items — and applications for such license requirements are usually denied.

Procurement of telecommunications equipment

The U.S. further tightened regulations for transactions of items subject to EAR by utilizing the system of re-export control, by which U.S. laws are effectively applied to items of U.S. origin that are shipped from a country outside of the U.S. to a third country.

In 2020, it added a new “military end user list” to restrict exports and re-exports of items subject to EAR to those determined by the U.S. government to be military end users in countries of concern.

Under this rule, if a firm is identified as a military end user in a country of concern, exports, re-exports or transfer of any covered item to that user requires a license issued by the U.S. Department of Commerce, even if the item is destined for civilian end-use.

Moreover, regarding federal procurement, section 889 of the 2019 NDAA prohibits government agencies from procuring telecommunications or video surveillance equipment, systems or services provided by certain companies that are deemed to pose risks.

U.S. government agencies stopped using such equipment and services from five Chinese firms listed in section 889: Huawei Technologies, ZTE, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, Dahua Technology and Hytera Communications.

Meanwhile, in 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration conducted comprehensive supply chain assessments for four critical products: semiconductors, large-capacity batteries, pharmaceuticals, and critical minerals and materials.

In February, the U.S. government released six additional supply chain reports in the following areas: defense; public health and biological preparedness; information and communications technology; energy; transportation; agricultural commodities and food products ecosystem.

The moves are aimed at breaking away from dependence on China regarding those sensitive technologies and key industries by boosting domestic production and cooperating with allies that have major companies in the fields.

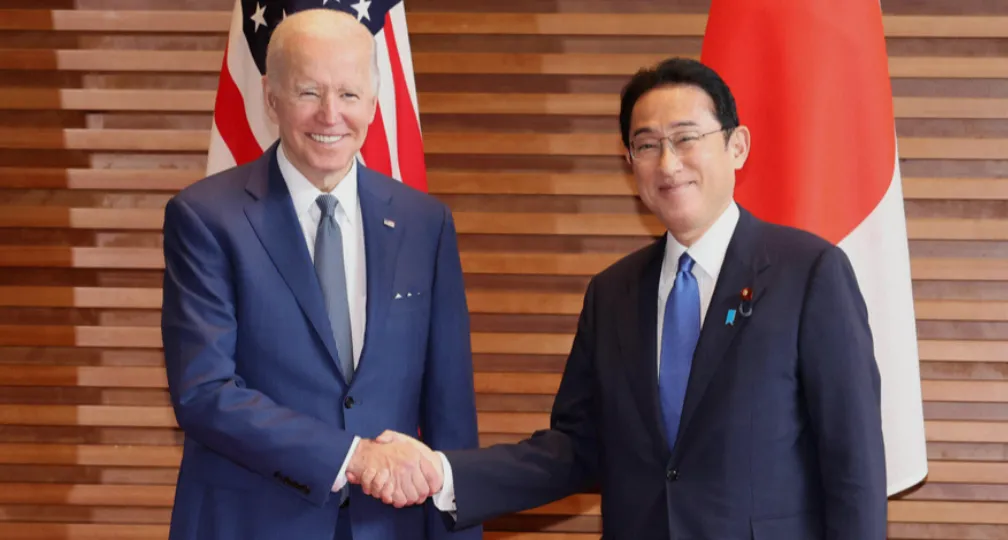

U.S.-Japan cooperation

Japan’s economic security framework is being designed in line with economic security policies that have been implemented by the U.S. government.

As for funding the development of cutting-edge technologies, the key part of the economic security promotion law, it has been reported that the government plans to focus on 20 priority technology fields.

The 20 fields mostly match the 14 emerging and foundational technologies listed by the U.S. under the ECRA.

The sectors that are unique to Japan’s list are: advanced energy; energy storage; chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear materials.

This indicates Japan’s intention to coordinate policies with Washington over development of key advanced technologies while making clear its own priorities.

Policy coordination with the U.S. concerning supply chains and export control is particularly important.

Efforts should be made to strengthen control on supply chains not only in Japan and the U.S. but also among the “Quad” framework of Japan, the U.S., Australia and India, as well as among Japan, the U.S. and South Korea, and among the Group of Seven members.

On the other hand, Japanese industries have criticized the U.S. for applying its export control measures on re-exports.

Japan and the U.S. must regularly exchange information on the designation of emerging technologies and end users of concern.

U.S. export control measures, including the entity list and the military end user list, should not be determined unilaterally by the U.S. but through negotiations with its allies.

In order for that to happen, it is essential to make high-level negotiations under the framework of the economic “two-plus-two” meeting of ministers a place for policy coordination.

At the same time, Japan should fundamentally boost the domestic development and use of civil technologies also from the perspective of strategic inevitability.

It is vital to thoroughly identify materials, underlying technologies, basic research and fundamental technologies held by Japanese industries and nurture emerging technologies that contribute to Japan’s defense.

(Photo Credit: The Mainichi / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Managing Director (Representative Director), International House of Japan,

President, Asia Pacific Initiative

JIMBO Ken is Professor at the Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University. He served as a Special Advisor to the Minister of Defense, Japan Ministry of Defense (2020) and a Senior Advisor, The National Security Secretariat (2018-20). His main research fields are in International Security, Japan-US Security Relations, Japanese Foreign and Defense Policy, Multilateral Security in Asia-Pacific, and Regionalism in East Asia. He has been a policy advisor for various Japanese governmental commissions and research groups including for the National Security Secretariat, the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His policy writings have appeared in NBR, The RAND Corporation, Stimson Center, Pacific Forum CSIS, Japan Times, Nikkei, Yomiuri, Asahi and Sankei Shimbun. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University

View Profile-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

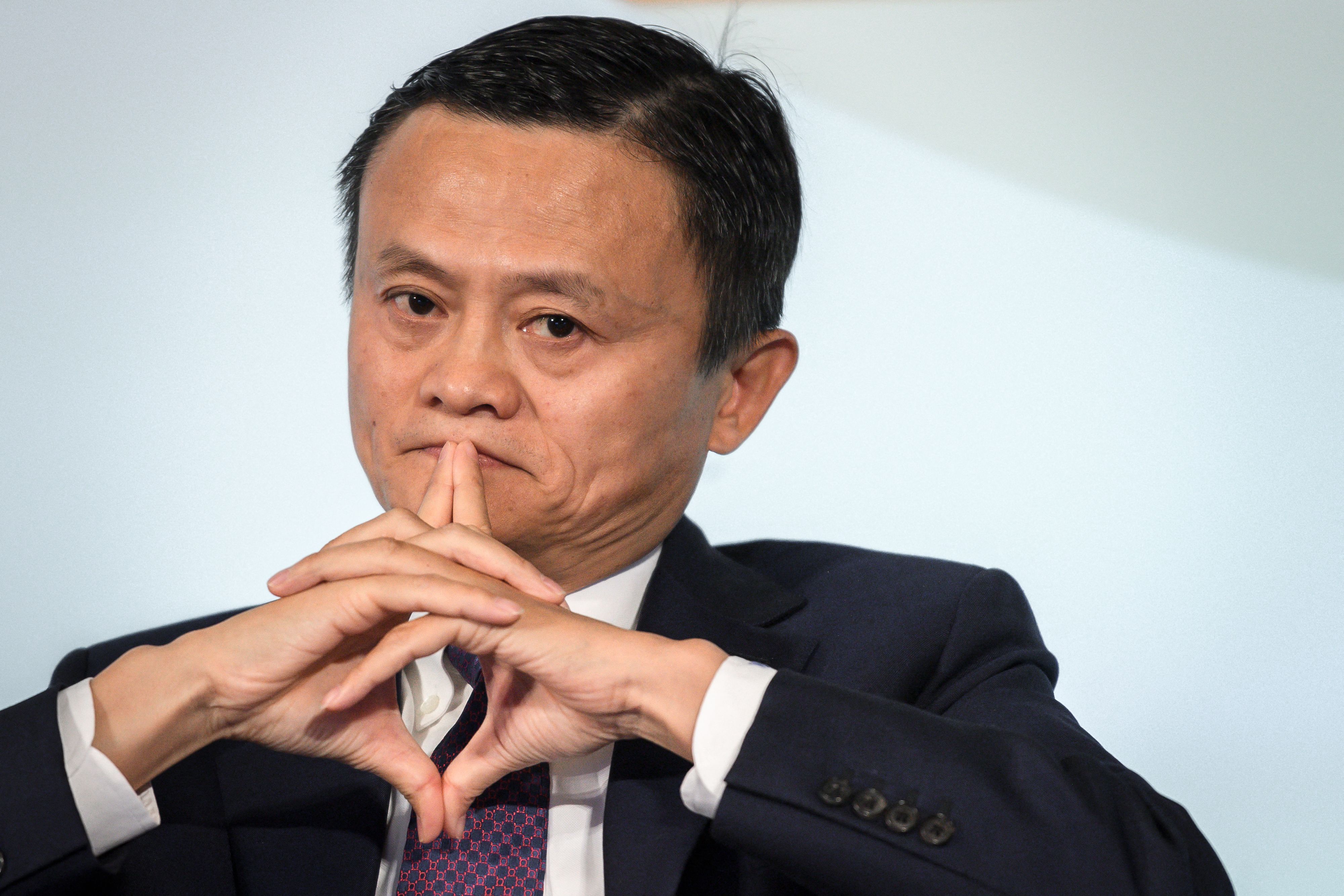

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06

Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25