Japan needs to take measures against China’s geoeconomic strategy

The international situation changed drastically after Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24 and when China conducted large-scale military drills in the waters around Taiwan in early August.

Facing such military threats, European and Asian countries are quickly moving to strengthen their own defense capabilities and step up institutional security cooperation.

What is making things more complicated is that along with such military tensions there are growing economic security concerns.

Countries are gaining stronger motives to implement so-called partial decoupling — economically decoupling from China and Russia for supply chains and trade in areas involving national security. Such moves are further pushing structural changes in the global economy.

Under such circumstances, geoeconomics is a useful approach to analyze any situation where politics and economics are closely linked.

Looking back at the history of geoeconomics in China-Japan relations, separating political issues from economic cooperation had been the mainstream for a long period of time.

This was a result of both countries recognizing their geographical proximity as an advantage while political options were limited under the Cold War structure.

Before normalizing diplomatic ties in 1972, the main point of Japan’s policy of separating politics from economics had been to expand economic exchanges with mainland China while maintaining a political relationship with Taiwan.

In other words, the separation of politics from economics had been Tokyo’s pragmatic approach to combining its substantial exchanges with China and official relationship with Taiwan.

Even after historical disputes emerged between Japan and China in the 1980s and territorial concerns over the Senkaku Islands caused friction in the late 2000s, the two countries maintained their economic ties interdependently. Keeping economic activities at a distance from politics worked for the benefit of both parties.

Needless to say, such a relationship was built against a backdrop of globalization, blurring national borders in the economic arena.

Today, 50 years after the normalization of diplomatic relations, efficiency-oriented neoliberalism is receding and politics and economics are again becoming indivisible.

The global economic slowdown is prompting more governments to become protectionist, symbolized by policies putting their own countries first.

Nevertheless, the Japanese economy cannot be sustained without China.

How should Japan’s future China strategy look?

Geoeconomics in China

The analytical perspective of geoeconomics, which has now taken root in Japan, was introduced in China in the 1990s, becoming one of the buzzwords in the field of international politics.

In China, geoeconomics is basically defined as a research area that integrates geography and economics.

There is no fixed definition for the term in the country, with many recognizing it as a concept of describing political and economic relationships between countries and some using it simply to discuss economic partnerships in certain regions.

It is notable that researchers of geoeconomics in China have applied the analytical perspective of the core-periphery model of commodity chain research.

Researches widely share the understanding that the regional economy in East Asia has created a supply network centered in China and that the centricity of China is continuing to increase within the network.

Such a view is not incorrect, considering that in the research of so-called global value chains examining international value sharing, international production systems are regarded as being made up of three regional value chains comprising the tripolar network of Asia, North America and Europe. Global value chains refer to when the different stages of the production process are located in different countries.

However, we need to pay attention to the fact that Chinese researchers often bring up this issue in the context of a strategy and set a goal of raising the country’s global discourse power — increasing China’s standing on the world stage by promoting China-led narratives — and obtaining the power to lead global governance through geographically expanding its centricity.

For instance, discussions on the Belt and Road Initiative that increased in the 2010s tended to focus on estimating the economic effects of connections brought about by the initiative’s projects and emphasize the global spread of the initiative beyond regional boundaries.

Also, in assessing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, China tends to stress the regional broadness of the framework.

A recognition of the global situation based on such geoeconomic theory also has an affinity with the Hua-Yi order, an international state system from hundreds of years ago, centered on China. Amid intensifying competition between the United States and China, such a recognition is also spreading in the form of Beijing’s moves to further take in the so-called Global South.

‘Unity and cooperation’

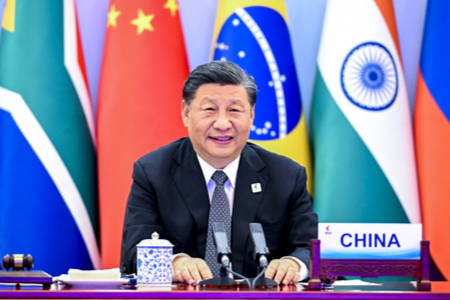

As Chinese President Xi Jinping’s administration boosts economic policies with other countries, the key policy that we should pay attention to is the Global Development Initiative (GDI).

Xi himself proposed the GDI at the U.N. General Assembly in September 2021, basically aiming to accelerate the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that includes Sustainable Development Goals.

China has been working to promote the initiative within the U.N., hosting a high-level meeting of the Group of Friends of the GDI at the U.N. headquarters in New York on May 9, attended remotely by 53 countries.

Beijing is trying to win the support of the international community by using the keyword “development.”

Taking the global economic slowdown as an opportunity, China is steadily getting developing countries on its side. In doing so, in addition to the U.N., the Xi administration is focusing on the emerging BRICS — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) initially comprising China, Russia and Central Asian states.

During a telephone call between Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin on June 15, Xi said that “China is willing to strengthen communication and coordination in such important international and regional organizations as the U.N., the BRICS and the SCO, promote unity and cooperation with emerging markets and developing countries, and push for the development of the international order and global governance towards a further fair and rational direction.”

Economic assistance

China’s emphasis on BRICS and the SCO implies its willingness to step up cooperation with Russia, a member of both frameworks.

Currently, India is the only other country that is a member of both mechanisms. But Iran, which officially joined the SCO in September 2021, filed an application on June 28 along with Argentina in a bid to join BRICS, a clear indication of the country approaching China and Russia.

The High-level Dialogue on Global Development, held on June 24 on the margins of a BRICS summit meeting held a day before, was attended by BRICS members and 13 other countries including Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

At the opening of the dialogue, Xi stressed that China “has always been a member of the big family of developing countries.”

He said China will upgrade the South-South Cooperation Assistance Fund to become the Global Development and South-South Cooperation Fund, add $1 billion to the fund on top of $3 billion already committed and increase aid to China’s U.N. Peace and Development Trust Fund to further support cooperation under the GDI.

At the same time, Xi called on emerging and developing countries to cooperate to “shape a global governance system and institutional environment that are more fair and rational.”

Thus, Xi’s remarks indicate that behind his administration’s economic assistance lies the goal of altering the existing international order.

Sphere of influence

The Xi administration is trying to increase its sphere of influence by obtaining support from developing and emerging countries.

The effort is aimed both at forming a buffer zone in competition with industrialized countries centered on the U.S. and shifting to a competitive paradigm by raising its international discourse power through converting its economic attractiveness to political influence.

The Xi administration’s blueprint is to materialize China’s dual circulation strategy — expanding domestic demand, reducing dependence on foreign markets and, at the same time, remaining open to the outside world — by making emerging and developing countries economically dependent on China and to take leadership in forming new rules at international institutions such as the U.N. based on the power of the majority.

And what comes beyond that probably is gaining structural hegemony.

Japan should make use of China’s economic power to spur growth in Asia, and at the same time it needs to disable Beijing’s political influence.

In doing so, it is beneficial to take the geoeconomic perspective that momentum cannot be decided only in terms of the size of an economy.

For instance, China has applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, signed in 2018, which means it has to present measures that follow CPTPP rules and negotiate with current member countries.

In other words, it is possible to control China’s unrestrained influence to some extent through the filter of rules.

One way to avoid being engulfed in the Chinese-style order would be to draw multilayered lines of multilateral frameworks to hamper Beijing’s attempt to exercise influence in the economic arena beyond national borders.

On the other hand, Beijing has a point in asserting that the existing international order should be changed based on demands from emerging and developing countries, and this is actually a cohesive argument.

It is necessary for Japan to work with other industrialized countries to build an international order that matches the current international situation and incorporates diverse values.

Visiting Senior Fellow

Naoko Eto is a professor in the Department of Political Science at Gakushuin University. Her main research interests include East Asian affairs and Japan-China relations. She is a member of the Expert Committee on Industrial and Technological Infrastructure Strengthening for Economic Security at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Industrial Structure Council, METI and the Customs and Foreign Exchange Council at the Ministry of Finance (MOF). She was also a visiting research fellow at the School of International Studies, Peking University, the East Asian Institute, Singapore National University, and a visiting senior fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Department of Political Science, Gakushuin University

View Profile Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07