Ukraine war highlights private sector’s role in conflict

While relatively new, 21st century-style factors can be observed in this war, such as the use of drones and satellite information as well as cyberattacks, 20th century-style technologies and operations are being used at the same time, including besieging cities with heavy armaments and airborne troops conducting occupation operations.

Needless to say, it is not rare for new and old technologies to be used in a mixed manner in warfare. Such a case was seen even in 1991 in the Gulf War, which triggered debate over a revolution in military affairs.

Outside the battlefield

What is notable in the latest war is that private corporations and citizens have been more involved.

This is also deeply linked to the characteristics of today’s technological innovations — the omnipresent spread of emerging technologies in the private sector.

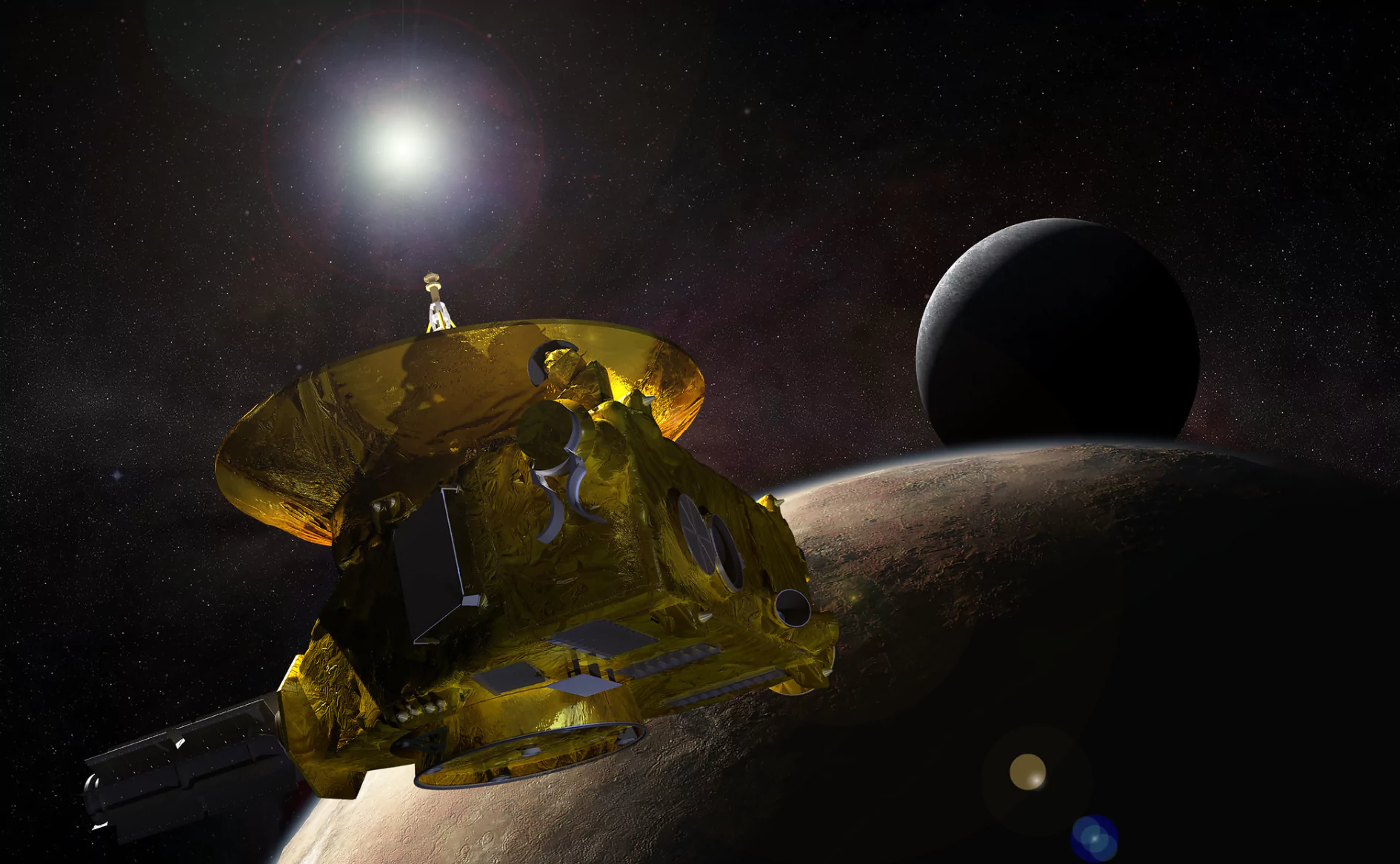

For instance, U.S.-based firm SpaceX is providing the Ukrainian government with its Starlink satellite internet service to operate drones. Although the use of drones is not necessarily a new form of warfare, it is noteworthy that a foreign private firm directly offered the platform for operation.

It is difficult to ignore the fact that today an environment has been created for more people — not only prominent power-players like SpaceX founder Elon Musk, but also ordinary citizens — to take part in warfare in a timely manner.

Following the start of the Russia-Ukraine war in late February, Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s digital transformation minister, called for the creation of an “IT army” through his Twitter account, encouraging people to launch distributed denial of service cyberattacks on Russian companies and organizations.

In addition to hacker groups such as Anonymous, it is believed that a large number of unidentified individuals heeded Ukraine’s call and launched cyberattacks against Russia.

Maxar Technologies, a satellite images provider, is also supporting the Ukrainian troops by offering information, representing one of the outcomes of the spread of technologies in the private sector.

Moreover, experts in the private sector across the world are conducting open source intelligence, carefully analyzing publicly available information including that released by governments or data collected from social media and satellites.

By releasing the results of the investigations widely via media organizations and social networks, they are playing an important role in forming a cognitive framework for warfare.

Through making the course of the war and the wretched situation widely known, they are also helping form public opinion against Russia. This means how the justice of war is discussed is becoming more strongly connected with the improvement of the private sector’s ability to grasp the situation at the battlefield.

Ever since the 2014 Crimea crisis, focus has been on Russia’s hybrid warfare, and in the latest war in Ukraine, people were on high alert over Moscow’s skillful war operations, including high-level information and cyberwarfare.

However, as the war went on, what became clear was the aspect of the government losing control over the subject of intervention and information due to the spread of technologies.

Private-sector participation

If the spread of emerging technologies in both military and industry arenas is becoming an irreversible trend, such changes can have a lasting influence on the world for years to come.

The impact would be more than case-by-case changes on battlefields.

Obviously, issues concerning the use of emerging technologies across the border between military and civilian applications have already been discussed on various occasions. But the bigger problem is that the private sector — especially entities, or even individuals at times, from countries that are not directly involved in war — is beginning to directly affect battle.

Aside from the issue of technological innovations, the governments fighting a war taking in the abilities of the private sector are, in part, adopting a structure close to the issue of private military companies (PMCs), which came under the spotlight after the 2003 Iraq War.

That is to say there is the problem of states actively utilizing the “military power” within the private sector and that it comes with an adverse effect of states becoming unable to control it.

Looking from the standpoint of governments — particularly the United States, which has been conducting such military operations since the early 2000s — signing contracts with PMCs has been part of the trend of increasing military efficiency.

As its military size shrank with the end of the Cold War, the U.S. government worked on how to make the military structure more cost-efficient.

At the same time, however, legal systems to manage PMCs have not been mature enough, leading to lawless acts on battlefields becoming a serious problem.

In the Russia-Ukraine war, the Ukrainian government asked both foreign governments and citizens for support.

Such a request in itself is nothing unusual. But the latest war indicates a new issue arising as ordinary citizens in other countries are responding by not only calling on their government’s to take more action, but also by taking steps to directly participate in the war themselves.

Technologies such as cyber or space communications take ordinary citizens closer to battlefields, as they are not monopolized by states but are freely accessible and widely used by the private sector.

New tools of war

When such private sector power is used to support Ukraine, it tends to receive a lot of applause.

However, under current international rules, it cannot necessarily be determined as favorable that the private sector is conducting “support” closer to military action — different from moves like humanitarian assistance — that is not controlled by states.

There are at least two issues related to such assistance by the private sector.

First, if the private sector provides resources to a country involved in war — Ukraine in this case — in a form different from the diplomatic intentions of the government that is offering support, that might make the supporting government’s diplomatic message unclear.

Secondly, if the private sector exercises its power outside the chain of command of the government fighting a war, there arises an issue of who will be ultimately responsible for the management of the total power.

In any case, if there exist “weapons” that are not managed by public entities and the chances increase for such weapons to be used in state-to-state conflicts, it will further complicate the process of war escalation.

Even if Ukraine succeeds in defending itself and the private sector cooperation in war is recognized as an effective means to do that, the question remains whether such a mechanism is favorable for maintaining international order.

This, however, can be regarded as part of the wider issue today on regulations failing to catch up with the speed of the development and spread of emerging technologies.

Moreover, it is open to argument whether the tools of intervention in war discussed here should be regarded as “weapons” in the first place.

Whatever the case, if today’s wars are increasingly fought in the gray zone with the spread of such technologies, and the trend is irreversible, it becomes important to construct an international framework to control the effects of such a trend.

National security

Such an awareness gained through the Russia-Ukraine war is giving Japan the opportunity to think about what policies to take concerning dual-use technologies.

As attention is focused on efforts to put together specific policies related to economic security, it is not enough to only discuss the relationship between advanced technologies and businesses and academia.

There is also an urgent need to work on the issue of using and protecting cutting-edge technologies by taking their military applications into account.

Nevertheless, although the situation is gradually changing, there are still arguments in Japan that the military and civilian use of technologies should be separated and that the way to maintain peace is to restrict the military use of technologies as much as possible.

While such arguments have a point, it should be noted that the Russia-Ukraine war revealed one aspect of emerging technologies — how those intended for civilian purposes impacted battlefields through their use by ordinary people who are not enlisted in the armed forces.

In other words, even if certain technologies are widely available in the civilian market, there is still the possibility that it may affect the battlefield.

If that is the case, in thinking about the issue of dual-use technologies, it is becoming ever more important to refer to specific cases in battlefield conflict, like the Russia-Ukraine war, and consider how to use and regulate technologies without being bound to the dichotomy of military and civilian applications.

(Photo Credit: picture alliance / Getty Images)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

SAITOU Kousuke is a professor at the Faculty of Global Studies, Sophia University, Japan. He received his Ph.D. in International Political Economy from the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Japan. Prior to joining Sophia University to teach international security studies, he was an associate professor at Yokohama National University, Japan. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Faculty of Global Studies, Sophia University

View Profile-

Lessons for Japan from Russia’s war in Ukraine2026.03.05

Lessons for Japan from Russia’s war in Ukraine2026.03.05 -

U.S. Supreme Court Decision to Block IEEPA Tariffs2026.03.05

U.S. Supreme Court Decision to Block IEEPA Tariffs2026.03.05 -

U.S. LNG and Japan's Sea Lanes: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.03.03

U.S. LNG and Japan's Sea Lanes: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.03.03 -

Dependence and Diversification: Canada’s Middle-Power Strategy2026.03.02

Dependence and Diversification: Canada’s Middle-Power Strategy2026.03.02 -

Attack on Iran: What Comes Next for the Gulf & The Oil Crisis?2026.03.02

Attack on Iran: What Comes Next for the Gulf & The Oil Crisis?2026.03.02

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08