The populism trap that is throwing U.K. politics into chaos

It is extremely rare for the country to see such a turnover of the prime minister in a short period of time. Five people have served as prime minister in the six years since 2016.

What is happening in British politics?

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the U.K. led by Johnson and Truss, who served as foreign minister in the former’s administration, imposed the harshest sanctions on Russia among the Group of Seven countries and advocated the need to fully support Ukraine.

However, there are concerns that U.K. policies in support of Ukraine might change, with Sunak having had little experience in foreign affairs and national security, and having been accused of being weak on China.

To begin with, what are the factors behind such frequent changes of prime minister in the U.K.?

The first reason is Brexit.

The U.K.’s decision to withdraw from the European Union based on the results of a national referendum, held in June 2016, is continuing to give instability and uncertainty to its politics six years on.

Johnson became prime minister in July 2019 with the slogan “Get Brexit done,” and completed the process on the last day of 2020.

However, the U.K. government showed an intention to unilaterally change the post-Brexit deal on Northern Ireland that it signed with the EU, leading to a worsening of relations between them.

Furthermore, labor shortages brought about by Brexit are putting the brakes on the country’s economic growth.

The second reason is the confusion among the U.K. government regarding COVID-19.

Johnson initially did not take the pandemic seriously enough and failed to take necessary measures.

Even worse, Johnson and some other senior officials from the administration were found to have attended several parties held in Downing Street during the COVID-19 lockdown. The breaching of laws in the so-called “Partygate” scandal increased distrust in politics.

The third reason is the soaring energy prices, triggered by sanctions against Russia, pressuring people’s livelihoods, resulting in dissatisfaction toward the government.

People’s criticism over the scandal around the Johnson administration was fueled, in part, by their anger over the rising costs of living.

According to the world economic outlook released by the International Monetary Fund on April 19, the U.K. economy is expected to grow 1.2% in 2023, which means it is set to have the slowest growth among G7 members next year.

The economic growth rate in the U.K. will also be the second lowest among the Group of 20 countries — after heavily sanctioned Russia.

While the U.K. economy is already on the verge of serious crisis, the British public is worried of deeper damage due to political confusion. Behind such concern is the spread of populism in British politics.

Populist politics

As the home of parliamentary democracy, the U.K.’s political system has been regarded as a model by many democracies around the world.

Thanks to the two-party system that enabled stable change in administrations, reforms were conducted in politics, bringing new political waves to the global community, including the establishment of a welfare state after World War II and a political tide of neoliberalism since the 1980s.

However, the country is now being engulfed in a serious wave of populist politics.

In July 2019, Conservative Party members chose Johnson, who had repeatedly made populist remarks, to head the party instead of Jeremy Hunt, who employed a more rational and practical approach to politics.

After becoming prime minister, Johnson often made light of laws, acted provocatively toward countries on the European continent and overplayed the perceived greatness of the U.K.

Through such remarks, he led the public to become enraptured with words sweet to the ears and to face away from difficult realities.

In September of this year, Truss, who was seen as catering to both the wealthy and the poor, was elected in the party leadership race instead of Sunak, who was highly praised for his fiscal policy.

The financial markets, however, quickly lost trust in Truss during her extremely short-lived term, bringing about declines in the pound and stocks.

Hunt, who replaced Kwasi Kwarteng, a very short-serving chancellor of the exchequer, reversed most of Truss’ tax-cutting plans, in a bid to rescue the U.K. economy from turmoil.

Truss, who lost the trust of the markets, her party and the public, was forced to step down, earning the embarrassing title of the shortest-serving prime minister in the history of U.K. politics.

During the six years following the referendum on Brexit, the U.K. has constantly faced challenges — including Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic and the imposing of economic sanctions on Russia — resulting in the country suffering economic downturn.

The public came to be more fascinated by populist claims repeatedly praising the country rather than making efforts to overcome the difficulties through realistic policies.

Looking away from difficulties

In the December 2019 U.K. general election, the Conservative Party led by Johnson secured a big win, and his administration gained the confidence of the public.

But this meant the public looked away from economic and political hardships the country was facing.

Sunak, who became the new prime minister in October of this year, is advocating more practical economic policies compared with his two predecessors, showing a stance of sincerely facing the country’s difficulties.

Three months before that, even, when he was running in the party leadership election against Truss after Johnson announced his resignation, Sunak harshly criticized Truss’ unrealistic fiscal policy plans as “a fairy tale.”

Embarking on a spree of public borrowing — without a clear plan for how to finance it — in order to appeal to all classes of people will bring about serious inflation and the collapse of the U.K. economy.

Sunak won deep trust from Conservative Party members as he steered the economy through the COVID-19 pandemic as chancellor of the exchequer under Johnson.

However, the U.K.’s challenges are not simple enough to let Sunak handle the government stably.

With the coming of winter, the people need to consume more energy such as electricity and gas for heating.

But the rise in energy prices, partly triggered by the war in Ukraine, has already been placing a heavy burden on people and companies in the U.K. and Europe.

The new Winter of Discontent

In 1978 and 1979, a wave of strikes erupted across the U.K. as workers rejected the attempt by the James Callaghan administration led by the Labour Party to impose wage limits in the face of rising inflation. The period of economic and social confusion came to be known as the Winter of Discontent.

This winter could possibly become the new Winter of Discontent, although the factors behind it differ from the previous one.

It is possible that the nightmares of low growth and inflation will torment people’s lives again.

The Sunak administration is facing the challenge of how to find the best equilibrium of helping impoverished people while maintaining strict fiscal discipline.

If the administration fails to meet the challenge, mutual distrust and frictions between the government and the public will intensify.

In a speech delivered on the day he became prime minister, Sunak said, “I will place economic stability and confidence at the heart of this government’s agenda.”

“I will unite our country, not with words, but with action,” he said, indicating a breakaway from the populist politics of Johnson and Truss.

But can Sunak overcome the threat of a new Winter of Discontent?

The war in Ukraine is posing a huge challenge to democratic countries: What level of costs can people bear in order to follow international norms?

Japan is no exception.

As the war continues, Japanese people and firms will also be heavily burdened with soaring energy prices.

In such a situation, will people avoid paying high costs and be attracted to populist claims? Or will they squarely face structural problems and work sincerely and patiently to solve them?

As many point to the emergence of ideological confrontation between democratic and authoritarian regimes, the people’s choice will have a great impact on the future of democracy.

(Photo Credit: AP / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Director, International House of Japan

Group Head, Europe & Americas,

Director of Research, Asia Pacific Initiative

Director, International House of Japan

Yuichi Hosoya is professor of international politics at Keio University, Tokyo. Professor Hosoya was a member of the Advisory Board at Japan’s National Security Council (NSC) (2014-2016). He was also a member of Prime Minister’s Advisory Panel on Reconstruction of the Legal Basis for Security (2013-14), and Prime Minister’s Advisory Panel on National Security and Defense Capabilities (2013). Professor Hosoya studied international politics at Rikkyo (BA), Birmingham (MIS), and Keio (Ph.D.). He was a visiting professor and Japan Chair (2009–2010) at Sciences-Po in Paris (Institut d’Études Politiques) and a visiting fellow (Fulbright Fellow, 2008–2009) at Princeton University. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Faculty of Law, Keio University

View Profile-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

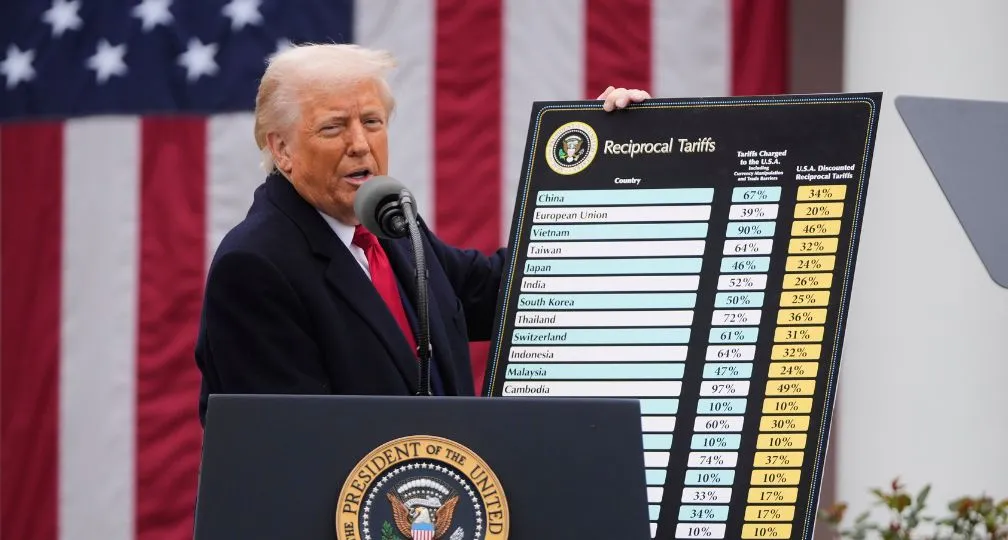

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06

Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25