Why the semiconductor competition between the U.S. and China is significant

This illustrates how extremely significant the event is, representing a turn of the tide in U.S.-China relations. To explore this issue, we can focus on how U.S. economic security is situated in the framework of confrontations with China.

Economic security

The term “economic security” has been used frequently in Japan, with the country having enacted a law in May to promote the issue.

However, the term is not clearly defined in the U.S., where economic security is sometimes used to describe social security or job security, often indicating protectionist policies.

To avoid confusion, the articles in this series, when discussing economic security, will focus on issues included in Japan’s concept of economic security, such as strengthening the resilience of supply chains and preventing leaks of sensitive technological information.

Another point to take into account in discussing economic security in the U.S. is that its purpose is different from that of Japan.

When we talk about economic security in Japan, we think about measures to avert the coercive efforts by other countries deliberately suspending exports of certain goods or embedding malicious software in key infrastructure.

But when the U.S. says it is strengthening supply chains, it means preparing not only for intentional disruptions of supplies by other countries but also for supply cuts brought about by natural disasters or COVID-19 lockdowns.

In that sense, achieving economic security in the U.S. means ensuring a stable supply of goods through supply chains at all times regardless of whether the country is hit by intentional attacks by other countries or unintentional disturbances by natural disasters.

Economic security in the U.S. is much more broadly defined than in Japan, and Japanese officials must be aware that if they don’t recognize such differences, they may not be on the same page with their U.S. counterparts when conducting dialogues and negotiations.

The Thucydides trap

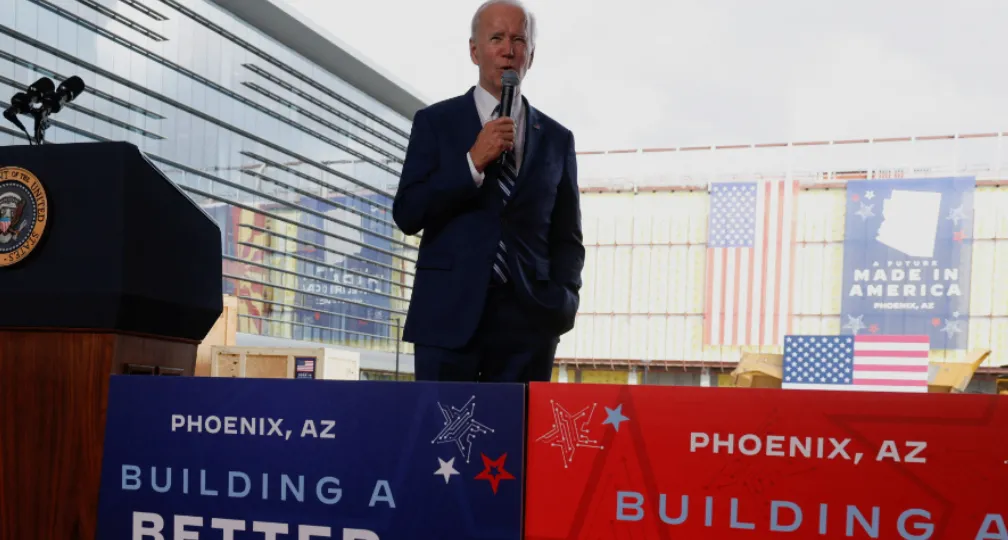

The issue of economic security, namely strengthening the resilience of supply chains, started to be taken up widely in the U.S. after President Joe Biden took office. But several related incidents occurred even before that, although they were not specifically termed as economic security issues.

An economic slump in the Rust Belt — the Great Lakes states with their long history as an industrial area that brought victory for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election — prompted the U.S. to put stronger pressure on China and aim to decouple the two countries’ markets. Believing that the industrial decline had been brought about by Chinese exports, the Trump administration imposed tariffs on imports from China under Section 301 of the U.S. Trade Act.

However, Washington’s dependence on Beijing did not change so easily, resulting in an increase in the U.S. trade deficit with China.

The Trump administration also found it problematic that many Chinese-made components were used in key U.S. infrastructure, and moved to exclude products made by Chinese companies such as Huawei Technologies, particularly from the next-generation 5G mobile network.

In this way, Washington has been implementing so-called economic statecraft — the use of economic tools to achieve foreign policy objectives — to put pressure on Beijing. Then the U.S. began to recognize the vulnerability of supply chains, as the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic since 2020 led to a global economic slowdown coupled with labor shortages in production and distribution, bringing about chip shortages.

Biden, immediately after taking office in January 2021, signed an executive order to review supply chains used by four sectors — semiconductors, large-capacity batteries, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals.

In parallel to the reviews, the executive order mandated a comprehensive review and risk assessment of the industrial bases relevant to seven federal departments. Particular focus was placed on assessing how much they were dependent on China.

As the U.S. had been recognizing China as “a strategic competitor,” Washington being dependent on Beijing means it is strategically vulnerable, and the Biden administration was concerned that Beijing could hold control over strategic chokepoints — critical goods that affect the entire supply chains.

The China trade policy of the U.S., including the Trump administration’s decoupling policy and the Biden administration’s strengthening of supply chains, represents a fierce competitive relationship.

The U.S., which has regarded free trade as the basic principle of international economic order since World War II, is trying to survive the competition with China, even if it means distorting the principle.

Such policies focusing on China can be interpreted as the “Thucydides trap” — a term coined by political scientist Graham Allison to refer to the likelihood of conflict to erupt when a dominant power is challenged by a growing power — occurring in the economic sector.

The U.S. dependence on China — the country that threatens Washington’s position in the global community — will create more vulnerabilities in the Thucydides trap, and the U.S.’ top priority is to avoid such a situation.

Why semiconductors?

The Thucydides trap is most apparent in the U.S.-China competition over semiconductors.

In regards to the new export controls on semiconductors announced by the U.S. in October, it must be noted that the situation surrounding chips differs largely from other sectors subject to U.S.-China confrontations, such as storage batteries, pharmaceuticals and rare earths.

China-made storage batteries occupy one third of the global market, and China also holds 70% of the market for materials, including lithium, to produce the batteries. The U.S. depends greatly on China also for active pharmaceutical ingredients.

It is estimated that China holds 80% of the global rare earths market.

However, the U.S. does not rely on China for semiconductors.

Taiwan and South Korea have strength in manufacturing advanced chips, while the U.S. is superior in designing such products. Japan, the U.S. and the Netherlands hold a dominant position in semiconductor production equipment.

China falls behind in all of these areas. The country imports high-end semiconductors from Taiwan and depends on Western countries for the design data and equipment used by its chip industry.

Even so, the U.S. is strengthening controls on the exports of semiconductors to China with the apparent aim of suppressing the growth of China’s chip industry and, in the meantime, cooperate with other Western countries to advance development of higher-end chips and widen the technological gap with China.

That is to say Washington is trying to strengthen the superiority of the U.S. and other Western countries so that it becomes difficult for China to catch up, therefore preventing Beijing from pushing growth in areas that require advanced semiconductors, such as smartphones and data-center servers, and, even more importantly, artificial intelligence, supercomputers and quantum technology.

Nevertheless, we must note the fact that the U.S.’ strengthened control over exports to China is restricted to advanced semiconductors and is not used for other chip products.

The U.S. is trying to maintain technological superiority and prevent the emergence of China because AI and quantum technology are significant as next-generation military technologies, and it is believed that having technological superiority in these areas is directly linked to maintaining military superiority.

That is why, although the U.S. doesn’t rely on China to supply the products, semiconductors are listed along with other areas such as batteries as a sector whose supply chain needs to be strengthened, and as a sector subject to working on partial decoupling from China.

Pressure on Japan and the Netherlands

Through the export control measures announced in October, the U.S. is attempting to maintain its military superiority by keeping semiconductor technology within Western countries and retaining the technological gap with China.

Japan and the Netherlands, which are globally competitive particularly in chip manufacturing equipment, were called on to introduce similar restrictions, to help stop China from developing technologies.

The U.S. put pressure on Japan and the Netherlands, urging the two countries to choose between their economic interests and Washington’s strategic objectives.

In other words, the U.S. was testing the two countries’ determination as its allies to strive to break the momentum of a rising power challenging a dominant power, avoid getting caught in the Thucydides trap and prevent China from challenging the U.S.

The Netherlands and Japan agreed to the measures on Friday, sources have said.

(Photo Credit: Reuters / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Director & Group Head, Economic Security

Kazuto Suzuki is Professor of Science and Technology Policy at the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, Japan. He graduated from the Department of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, and received his Ph.D. from Sussex European Institute, University of Sussex, England. He has worked for the Fondation pour la recherche stratégique in Paris, France as an assistant researcher, as an Associate Professor at the University of Tsukuba from 2000 to 2008, and served as Professor of International Politics at Hokkaido University until 2020. He also spent one year at the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University from 2012 to 2013 as a visiting researcher. He served as an expert in the Panel of Experts for Iranian Sanction Committee under the United Nations Security Council from 2013 to July 2015. He has been the President of the Japan Association of International Security and Trade. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09