New risks emerge as Xi administration moves ahead toward a dead end

Project Professor, Global Center for Asian and Regional Research, University of Shizuoka

China, which has been walking a path of reform and opening up since 1978, achieved high economic growth in the 2000s and played a role as the driving force of the global economy. But for democratic countries, China under Xi Jinping’s administration appears to have become a troublemaker in the global community.

To understand what lies behind Xi’s actions, it is necessary to look back to the era when Mao Zedong was leading the country.

Backtracking

In 1970, Mao jokingly said to American journalist Edgar Snow who visited Beijing that he cared about neither God nor law.

During China’s Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976, intellectuals were persecuted and hundreds of thousands of people are said to have been killed.

Some junior high and senior high school students, known as Red Guards, were the ones directly involved in persecuting intellectuals at the time.

All of the people who served in the Chinese Communist Party’s all-powerful seven-member Politburo Standing Committee in the first and second Xi administrations were of the same generation as the Red Guards, and most of them were former Red Guards.

The committee in the current Xi administration is also made up of members of the Red Guards generation.

Red Guards were the main players of the Cultural Revolution, shouting slogans like “To rebel is justified” and relentlessly attacking intellectuals and the wealthy class labeled as counter-revolutionaries.

In 1978, veteran politicians such as Deng Xiaoping returned to power, after falling into disgrace during the Cultural Revolution, and began to pursue a reform and opening-up policy, in part denying Mao and the Cultural Revolution.

As a result, the Chinese economy achieved a high rate of growth, becoming the world’s second largest.

Meanwhile, Xi, also of the Red Guards generation, does not deny Mao’s era but has dubbed it a time of difficult exploration.

Xi’s leadership team of the Red Guards generation fears that while liberalization led to economic development, it could make China deviate from Mao’s revolutionary track, possibly causing the Communist Party’s leadership to collapse.

In his speech at the party’s 20th National Congress in the fall of 2022, Xi used the term “uphold” 107 times — the second most used word — indicating his determination to maintain socialist policies and the Communist Party leadership.

On the other hand, “reform and opening up” was not ranked among the top 20 most frequently used words in the speech. This is a message that the Xi administration is shifting away from the reform and opening-up policy.

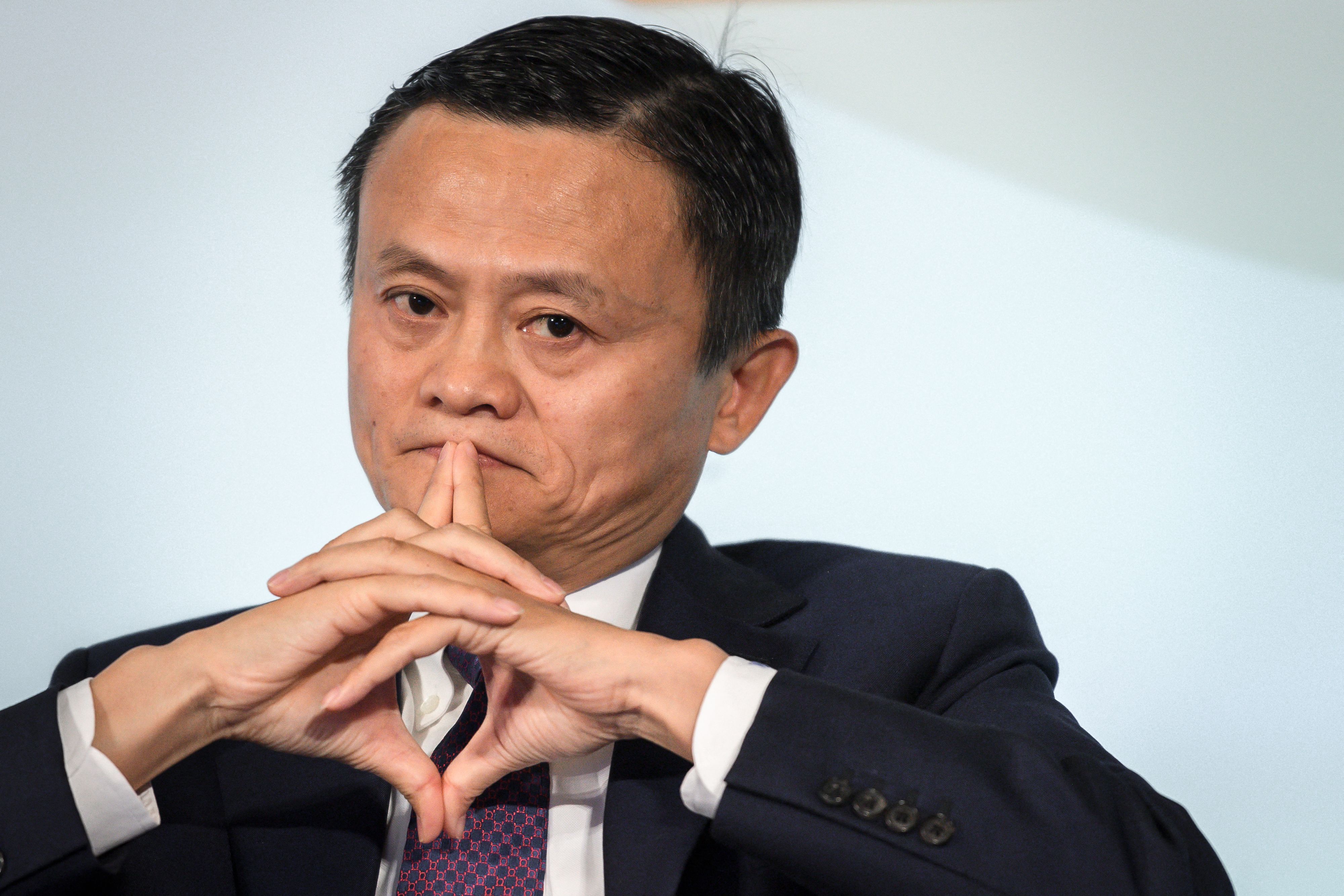

The Xi administration put an end to economic liberalization and tightened its grip on major private companies such as Alibaba. At the same time it made clear it was putting focus on state-owned companies.

During a meeting on state-owned enterprises (SOEs) held in 2016, Xi urged deepening the reform of SOEs to make them stronger, bigger and better. He has been making similar remarks repeatedly in his speeches since.

The Chinese government and the Communist Party may be able to make SOEs bigger through mergers and acquisitions, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they can make them stronger.

‘Chinese Dream’

Consequently, the stable growth of the Chinese economy was largely hampered by the Xi administration’s “Chinese Dream” of rejuvenating the country as a great power, and the Chinese society was thrown into confusion.

The Chinese government’s “zero-COVID” policy further fueled the economic downturn.

To overcome the situation, Xi appears to think it necessary to be on a par with past leaders like Mao and Deng in terms of ideology in order to take a firm grip on power.

The Communist Party’s leadership upholds the narratives that Mao created the People’s Republic of China and liberated the people, Deng made the people wealthier than in Mao’s era and Xi’s historic mission is to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and transform China into a global superpower.

Then how is the Xi administration trying to make China stronger?

So far, what it is doing is to restore a planned economy during Mao’s era, in which the state designates priority areas and concentrates all the resources on these areas.

However, in reality, allocation of resources by the government does not lead to efficiency.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s pursuit of the Chinese Dream provoked the United States, the world’s most powerful hegemony, triggering a fierce confrontation between the two countries.

The Xi administration’s miscalculation is that it is attempting to achieve a contradictory goal of realizing the rejuvenation of a strong China while taking its society and economy back to those of Mao’s era.

The Xi administration is apparently aiming for long-term rule.

It amended the Chinese Constitution to scrap the two-consecutive-term limit on China’s presidency, which enables Xi to remain in office beyond two terms, or 10 years.

To justify this amendment to the constitution, the Xi administration needs to make certain achievements.

But in reality, the administration has exposed its lack of governance, bringing about chaos in politics, society and the economy.

As dissatisfaction for the administration grew within the country, authorities had no choice but to exercise greater control over society, including restrictions on freedom of speech.

And, as such, the question arises over whether a country can become stronger when its society is under strict control.

The Xi administration’s policies are decided under a complete top-down system, exactly the same as during Mao’s era, with no bottom-up approach whatsoever.

On the other hand, it was significant for the Xi administration that, unlike in Mao’s time, there were various convenient surveillance tools, including artificial intelligence that censors internet content and facial recognition using security cameras installed all over the country.

It appears that the Xi administration is solidifying its power base, but is it really becoming stronger?

Rather, it looks like China’s national strength is weakening under the Xi administration, as the country eats into what had been accumulated during the period of reform and opening up that lasted for more than 30 years up until the administration of Hu Jintao between 2003 and 2012.

Most of China’s tech giants, such as Alibaba and Tencent, were established in the 1990s when Jiang Zemin was China’s leader. Such firms have now stopped growing and new leading companies have not emerged.

Wolf warrior diplomacy

The Xi administration, while strengthening control inside the country, has adopted an aggressive so-called wolf warrior diplomacy approach externally.

Although diplomacy is supposed to be aimed at increasing the number of allies in a game of making and breaking alliances, the number of China’s allies has been largely reduced under the Xi administration, as the country confronts democratic countries that have been supporting its economic development.

But why does the Xi administration take irrational actions that could lead to increasing its enemies?

That is because it fears that Western countries are attempting to democratize China.

We should also take note of the fact that the Xi administration does not follow the existing rules in the global community as it tries to achieve rejuvenation of its country.

What lies behind such actions is the notion of ignoring the rules — reflected in such slogans as “to rebel is justified” — the most important idea passed down from Mao to the current Chinese leadership of the Red Guards generation.

Such thinking leads to cases including easy amendment of the constitution in the country and the infringement of the intellectual property rights of multinational corporations.

Looking from the perspective of the Xi administration’s leadership, it seems that the leaders of the Red Guards generation worship power and believe in the idea that only the strong survive.

In other words, the Xi administration appears to think that since China has already become strong enough, it will not be a big problem even if it ignores existing international rules.

New risks

Looking back to China before Xi took power, there were political and social uncertainties as well as classic business risks such as Chinese companies not meeting delivery deadlines.

Today, under the Xi administration, China poses new risks as it fiercely confronts the world’s major economies with the aim of rejuvenating itself.

Such new risks not only disturb the international society, but also put China itself in a difficult situation.

The recent concerns worldwide over a possible Taiwan contingency are, in a broader sense, a part of such new risks.

There is a possibility that the lack of governance among the leaders of the Red Guards generation inheriting Mao’s spirit and the social and economic confusion caused as a result will accelerate in the future.

It is quite obvious that tightened social control and economic prosperity cannot coexist.

The U.S. and its allies, which have so far been most cooperative in pushing China’s economic development, will further raise the guard against China and distance themselves from the country.

If the Chinese economy stops developing, the Xi administration is highly likely to fall into a vicious cycle of being further forced into a corner.

The new members of the State Council under the third Xi administration were officially decided at the National People’s Congress held earlier this month, and most of them are Xi loyalists.

I’m quite certain I’m not the only one who is worried that the excessive concentration of power could force them to pay a heavy price.

(Photo Credit: AFP / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

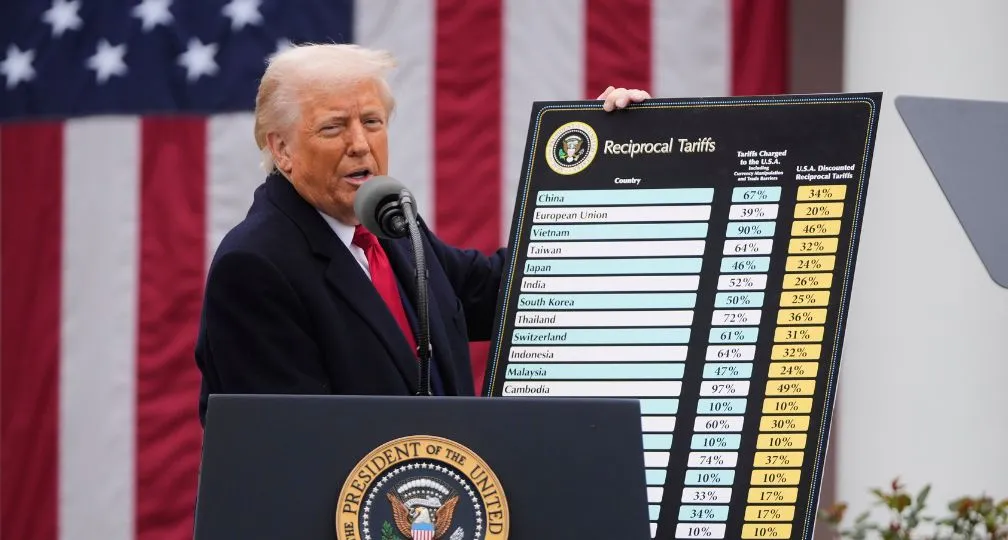

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 After tariffs: Is there a plan to restructure the global economic system?2025.04.03

After tariffs: Is there a plan to restructure the global economic system?2025.04.03