The future lies in helping to make China a responsible superpower

The G7 leaders’ communique stated that they stand prepared to build constructive and stable relations with China. And, while saying they don’t seek to thwart China’s economic progress and development, the leaders urged Beijing to play by international rules, addressed the challenges posed by its nonmarket policies and human rights situation, and called for the peaceful resolution of China-Taiwan issues.

But why is it important for G7 countries to make China play by international rules? And what do international rules mean for Beijing?

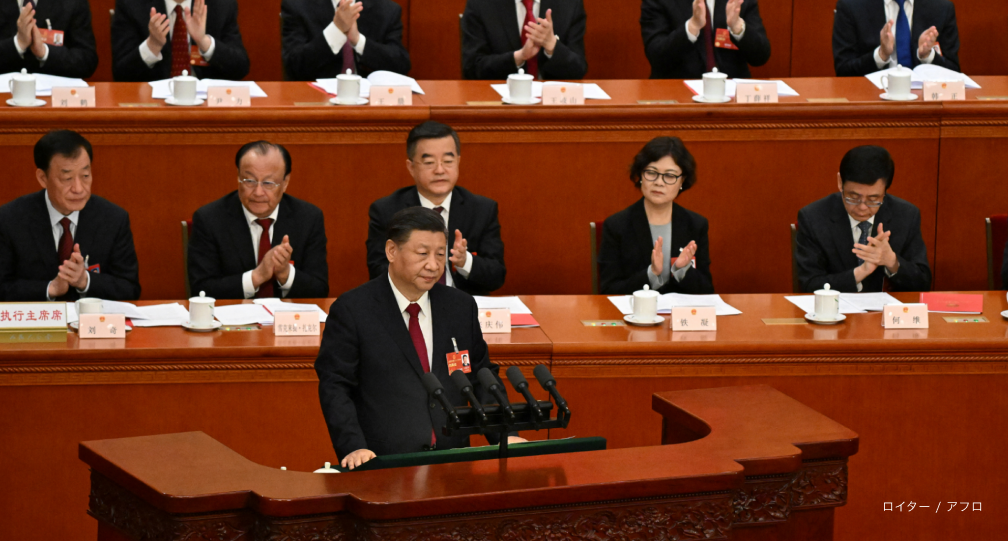

This article will focus on a “community with a shared future for mankind” — one of the key terms for Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s diplomacy — to look into the relationship between China and the international order.

Vision-driven policy

There is no clear-cut definition for a “community with a shared future for mankind.”

The term first appeared in 2012 in then-Chinese leader Hu Jintao’s report to the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, but there was no explanation as to its meaning. Supposedly the term serves to say that mankind has only one Earth to live on and should share a sense of community and common future, and that mankind needs to cooperate for peace, development and prosperity.

It is often the case for China to first table its vision and then follow it with actions connected to it. A typical example is the Belt and Road initiative proposed in 2013.

The initiative was proposed as a plan to develop and strengthen China’s economic ties with countries along the old Silk Road, the ancient land and sea trade routes that connected China and Europe. However, the criteria or the geographical scope of the projects subject to the initiative were not or have not been made clear.

Yet, following the submission of the initiative, Chinese government officials and companies actively promoted the idea, mentioning it repeatedly and labeling one project after another as being under the initiative.

It is said that more than 3,000 projects were launched and nearly $1 trillion of investments have been made under the initiative, but the precise details of the amounts are not made clear.

Around 2017, China began pushing forward a “community with a shared future for mankind,” without clear explanation of the term. U.N. Security Council Resolution 2344 on Afghanistan was adopted in March 2017 with mention of the term.

The phrase “a shared future, based upon our common humanity” was also included in a resolution on Africa’s development adopted by the U.N. Economic and Social Council in June the same year.

Chinese media outlets reported at the time that the Chinese concept of “community with a shared future for mankind” was incorporated into a U.N. resolution for the first time.

In March 2018, China’s National People’s Congress adopted an amendment to the country’s constitution to add the language to its preamble as the country’s goal.

It is now explained that “community with a shared future for mankind” proposed in 2012 should be brought into shape by the Belt and Road initiative announced by Xi in 2013 as well as the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI), which were all proposed by Xi after 2021.

The GDI, proposed in September 2021, focuses on the significance of economic development through practicing economic assistance and international cooperation, aiming for favorable reactions from developing countries.

The lack of details on the GDI, however, prompted cautious reactions from developing countries wondering if China is trying to rehash the U.N. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The GSI, presented in April 2022, seeks to uphold world peace and security by opposing unilateral sanctions and long-arm jurisdiction, committing to respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries and calling on all countries to practice “true multilateralism.” The initiative apparently is an antithesis of U.S. diplomacy.

The GCI, proposed in March of this year, calls for the diversity of civilizations instead of imposing certain values or models on others and seeks to spread the common values of humanity, including peace, democracy and freedom.

It is a message saying that the existing Western values should not be the only values accepted by the global community.

Goals of the vision

Why has Beijing begun emphasizing “a community with a shared future for mankind”?

In his speech on the occasion of the general debate of the U.N. General Assembly in 2015, Xi said China will continue to uphold the international order and firmly support the effort of increasing the representation and voice of developing countries.

Fu Ying, former Chinese ambassador to the United Kingdom, said in a speech in London in 2016 that international order is not exactly the same as the world order led by the U.S.

China has a strong sense of belonging to the U.N.-led order system, including the principles of international law, and is never fully embraced by the U.S.-led order system, she said.

Ever since its reform and opening-up, China has achieved high economic growth under the Western postwar international order.

However, following the 2008 global financial crisis and after becoming the world’s No. 2 economic superpower after the U.S., Beijing grew increasingly confident and became more assertive in its diplomacy.

China also began providing “international public goods” through proposing the Belt and Road initiative and launching the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in 2013.

Around the same time, the U.S. started to decrease its commitment to global issues, with then-U.S. President Barack Obama saying the U.S. was not “the world’s policeman” any more.

Still, the U.S. continued to criticize China, claiming it lacked human rights and freedoms, began to take up the issue of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and refused to accept China as an equal partner.

Beijing believed that the U.S. began hindering China’s development using international rules and values because its hegemonic position had been threatened by China’s growth.

Beijing wants to put a stop to Washington’s attempts to block its development and achieve continuous growth, its top priority goal.

To do so, it needs to counter the U.S. by gaining support from developing countries that have not benefited from the existing international order.

Moreover, China is aiming to propose new international initiatives and spread them by winning the approval of developing countries so as to divert U.S. pressure based on international rules.

Developing countries also have antipathy toward Western countries that interfere in their internal affairs by pointing out issues of human rights and lack of democracy.

Through “community with a shared future,” China is trying to present to the international community its own narrative to replace the Western-led international order.

Although “community with a shared future for mankind” is supposed to be an inclusive vision for all people sharing a common destiny, GSI and GCI — initiatives presented under the vision — contradict with the concept as they are an apparent offense against Western countries.

Moreover, Beijing has consistently said that China, as a responsible power, strongly supports the international system with the U.N. at its core and firmly upholds the international order underpinned by international law. However, it continues to ignore a ruling, unfavorable to China, handed down on a case filed under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. China’s behavior contradicts what it states.

Even so, the vision is increasingly included in China’s bilateral agreements with neighboring countries. Bilateral and regional versions of the concept are also being coined, including “a China-Kyrgyzstan community with a shared future” and “a China-Central Asia community with a shared future.”

Developing countries are accepting the idea, as they need China’s assistance to develop their economies.

China maintains that it upholds the U.N.-centered international system, and therefore it is likely that Beijing will keep on promoting its initiatives under the U.N system.

Because “community with a shared future for mankind” is ambiguous, it can be easily connected with a variety of behaviors so that China can say that it is promoting its initiatives.

In January last year, China launched the Group of Friends of GDI at the United Nations, joined by delegations from more than 100 countries and international organizations.

In September, then-Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi hosted a ministerial meeting for the group and said that China’s joint production of COVID-19 vaccines with other countries and its capacity-building and training programs are carried out under the GDI. He called on developed countries to participate in the initiative.

Beijing is using the initiative to show itself as a contributor to world peace and an advocate of the international order.

In February this year, China released a document describing its position on a political settlement for the Ukraine crisis. While it was only a position paper, China treated it as if it were a peace plan and sent a special envoy to visit Ukraine and Russia in May.

An agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia reached in March to restore diplomatic relations is touted as a good example of the GSI being put into practice, although it is still unclear to what degree China actually contributed to the deal.

Through such moves taken under its initiative, China is aiming at increasing its influence by weakening the Western order.

Dealing with Chinese initiatives

In response to China’s attempts to expand its influence, Japan and the G7 must protect the international order by presenting a clear vision to promote the peace and development of the international community.

It is particularly important to cooperate and make joint proposals for resolving urgent issues faced by the developing countries of the so-called Global South, including economic development, food security, energy and climate change. And G7 countries should fully implement their proposals without delay.

At the same time, we should be aware that, under “community for a shared future,” China is increasing its involvement in international issues such as assistance for developing countries and mediation of international conflicts.

Rather than simply denying all Chinese behaviors because they fall under the initiative, Japan should carefully watch each behavior and judge whether it is in line with international rules and whether it really contributes to the stability and prosperity of the international community.

In case we find self-righteousness or contradiction between words and behaviors, Japan can point this out to China and call on Beijing to improve its behaviors.

What Japan and the G7 should do is to fulfill their own responsibility in the international community in a more coherent way and at the same time engage more with China and lead the country to become a truly responsible power.

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

MACHIDA Hotaka is a visiting senior research fellow in Institute of Geoeconomics at International House of Japan. He joined the Institute in October, 2022. Prior to leaving his role in government, he served as a career diplomat in Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2001 to 2022, focusing on Japan-China relations. He studied at Nanjing University in China and Harvard University in the United States, followed by working at Embassy of Japan in China as second secretary from 2006-2008. After that, he was posted in China-Mongolia division in the Ministry and completed the negotiations with China over the issues of launching the “High-Level Consultation on Maritime Affairs” as well as finalizing the “Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR)” agreement. He also worked in Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) division in the North America Bureau in the Ministry leading the negotiations with the US on SOFA-related issues. He was counsellor in the Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations (2017-2020) and Embassy of Japan in China (2020-2022) covering the Security Council reform and Japan-China economic relations respectively. He holds a M.A from the Graduate School of Arts and Science at Harvard University, and a Bachelor from Law Faculty at Tokyo University.

View Profile-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

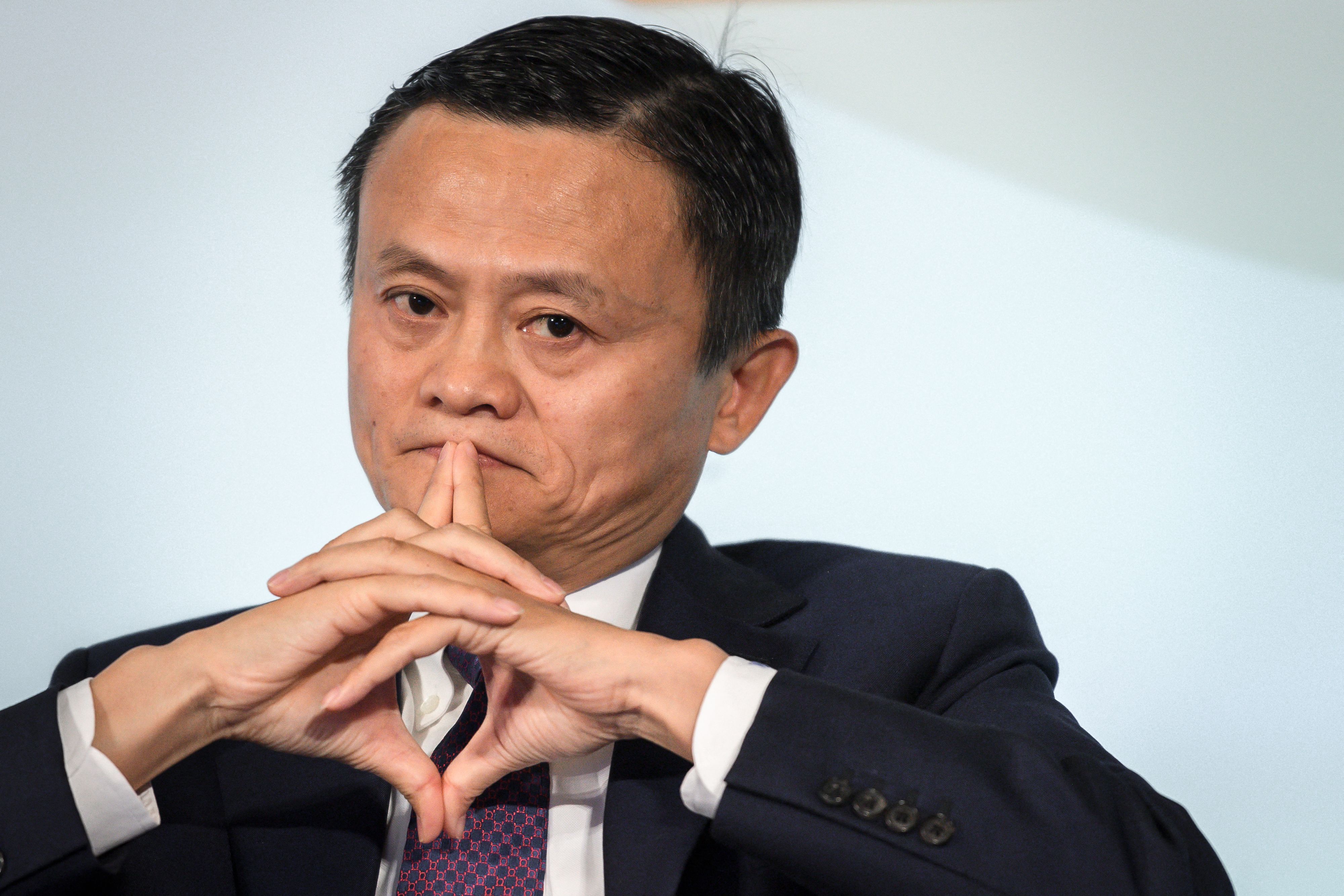

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

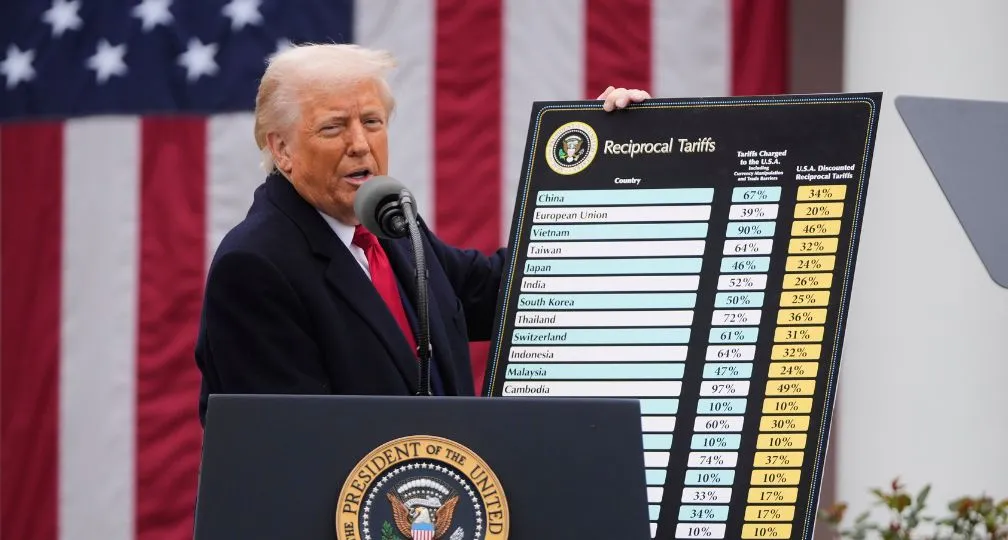

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06

Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25