A new tide of weapons imports, production and development

At the core of this defense capability is the defense equipment that guarantees the fundamental functions of national defense — including preventing, deterring, coercing and countering national security threats — and solidifies diplomacy to create a desirable national security environment for a country.

In 1901, weeks before becoming U.S. president, Theodore Roosevelt outlined his ideal foreign policy in a speech using the phrase “speak softly and carry a big stick,” indicating the idea that active diplomacy would be possible only through carefully mediated negotiation supported by the ultimate guarantee of defense power.

Weapons imports

Underlying technologies necessary to develop and produce defense equipment that serves as the core of defense capability are available worldwide, but the defense industrial base to enable the production of cutting-edge equipment is concentrated in a limited number of countries.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s data on the world’s top 100 companies in the military-related industry released in December, U.S. firms had the largest presence in terms of total arms sales in 2021, accounting 51%, followed by companies in China with 18%, the United Kingdom with 6.8%, France with 4.9% and Russia with 3%.

Except for the United States and Russia, it is difficult even for major economies to form a self-sufficient defense power only with domestically-produced weapons.

Most countries depend on overseas weapons markets to procure finished products. Even when they manufacture defense equipment at home, they often develop them jointly with foreign companies or through licensed production.

The focal point in thinking about today’s national security is how much each country depends on specific nations to maintain its defense capability.

While alliances that guarantee collective defense represent systematic relationships of dependence, the ratio of weapons imports including licensed production can be described as a hidden relationship of dependence with a certain country.

This is because if a country relies too much on imports from another nation in procuring weapons to build up its defense capability, it becomes difficult to conduct diplomacy with the exporting country without giving it consideration.

In the Indo-Pacific region, countries that import 50% or more of their weapons, and with 50% or more of the imports coming from their respective top supplier, are Australia (with its top supplier being the U.S.); India (Russia); South Korea (the U.S.); and Vietnam (Russia), according to data from SIPRI.

Meanwhile, countries that import 50% or more of their weapons but with their respective top supplier providing less than 50% of their imports are Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, indicating that the member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are acting cautiously in forming their relationships with certain superpowers.

On the other hand, only two countries in the region have sufficient domestic defense industrial bases and a weapons import ratio of 30% or less — China with 8.4% and Japan with 26.2%.

Suppliers’ bargaining power

A national strategy is not entirely bound by the percentage of imported weapons or the dependence on a certain country.

Countries ending up being attacked by the very weapons they exported are not rare, historically, as can be seen in the case of Central and Eastern European countries becoming NATO members while maintaining defense forces armed with Soviet-made weapons, and the fact that the countries are providing Ukraine with Soviet-made weapons to fight a war against Russia.

This is even more true for versatile small arms.

However, when a country relies on another power to acquire major defense equipment — fighter jets, tanks, war vessels and air defense systems — including training, maintenance and updating, the supplying country gains massive bargaining ability.

This is because it will become possible for the supplying country to ultimately threaten the national security of the importing country by coercing it to restrict or cut off exports.

Such restraint of a dependent relationship became most apparent in India following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Based on its close relationship with the Soviet Union during the Cold War era, India built up its defense system mainly with Soviet-made weapons.

As much as 66.5% of the weapons India obtained from foreign countries between 2000 and 2020 were made in Russia, and the country has been dependent on Moscow for most of its parts and ammunition replenishment.

Despite India’s recent efforts to reduce its reliance on Russian-made weapons, Moscow remained its top supplier in the five years between 2017 and 2021, accounting for 46% of its arms imports, far larger than 27% from France and 12% from the U.S.

The Indian army’s main tanks continue to be Soviet-made T-72 and T-90 models, and the Indian air force’s main fighter jet is the Russian Su-30MKI.

Only years ago, India procured S-400 surface-to-air missiles from Russia, with Turkey taking a similar move, much to the annoyance of Washington.

India’s dependence on Russia was the main reason it couldn’t make its stance clear in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

India abstained from voting on all of the six resolutions at the U.N. General Assembly in 2022 and 2023 that condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

New Delhi’s neutrality stood out as Western countries and their allies implemented strict economic sanctions against Russia.

It’s no wonder that questions arose over whether India shares the same values as Western countries and whether it can lead order as a regional superpower.

Escaping dependence on Russia

While India didn’t resonate with the Western-centric view of the world and trumpeted a narrative aimed at a multipolar world, it also recognized that its strategic autonomy is restricted by its excessive reliance on Russia.

Such a perspective was behind Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s moves to visit the U.S. in June and reach an agreement with U.S. President Joe Biden to strengthen bilateral defense cooperation.

The defense cooperation — a rare agreement between Washington and a country that is not a U.S. ally — includes coproduction of engines for the Indian Air Force’s next-generation fighter jets, India’s plans to procure MQ-9B SeaGuardian unmanned aerial vehicles, the repair by Indian shipyards of U.S. Navy warships and cooperation in the fields of semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

Washington apparently attaches importance to forming a strategic relationship with India. It hopes that increasing India’s dependence on the U.S. in the military sector will lead to building a long-term relationship with New Delhi.

India is determined to diversify its defense procurements, thinking this is what brings about strategic autonomy.

India’s case shows that a national strategy is greatly affected by the domestic production and import ratios of defense procurement and which country a state depends on to obtain specific equipment and technologies.

It is also essential to note that the three trends — promotion of international joint development of advanced defense equipment and technologies, the rise of emerging exporting countries and the “spinning on” of commercial technologies to the defense sector — provide nations with new options for international defense cooperation.

Many of today’s leading-edge defense equipment and technologies are developed under international joint initiatives to streamline technological transfers and research, development and production costs.

For instance, nine countries — Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Turkey, the U.K. and the U.S. — were involved in developing the F-35, the latest fifth-generation fighter jet.

U.S. partner countries in the international codevelopment program are classified into three levels according to the amount of investment and the degree of contribution, and the levels reflect the priority order given to the countries to subcontract manufacturing and procure the aircraft.

A new security model

International joint development of defense equipment has become a new strategic cooperation model between countries.

A typical example of such cooperation is AUKUS, a trilateral security partnership between Australia, the U.K. and the U.S. that agreed to provide Australia with U.S. Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines in the early 2030s and jointly work to design and build the next-generation nuclear-powered submarines.

Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines means that the Royal Australian Navy’s scope of operations will extend to a wide area in the Indo-Pacific region. It also represents its cooperation with the U.S. in the undersea domain and the U.K.’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific region.

Furthermore, we are seeing the rise of new weapons exporters that have not been major players in the international arms market until now. The leading country in this regard is South Korea.

In 2022, Seoul signed arms deals totaling $13.7 billion with Poland to supply military equipment, including 980 K2 battle tanks, 648 K9 howitzers, 48 FA-50 jets and 288 artillery rocket launchers.

It is said that South Korean weapons are highly competitive in terms of price and delivery time, as well as their ability to be customized according to the requests of different countries.

They have a high affinity with Western-made arms and their guarantee of high quality makes them a good second option, leading to expectations that their share in the international weapons market will increase.

South Korea’s arms exports in the 2017-21 period rose 2.8 times from the preceding five-year period, and the country emerged as the world’s eighth-largest weapons exporter, up from 14th, according to SIPRI.

The scope of international technological cooperation greatly expands if emerging consumer-use technologies are included.

Following the adoption of the three principles of transfer of defense equipment and technology in 2014, the Japanese government has also been deepening cooperation with countries aside from the U.S., such as the U.K., Italy, France, Israel, Australia and India.

Particularly in the areas of unmanned systems, robotics, directed energy, artificial intelligence, space and cyber, the horizons of international technological cooperation aimed at spinning on consumer technologies are broadening more than ever before.

Strategy for Japan

Amid such new tides regarding defense equipment and technological cooperation, Tokyo must make its big step forward to build a desirable national security order.

Japan, which has relied on the U.S. for almost all of the joint development programs of major defense equipment, decided to develop a next-generation fighter aircraft jointly with the U.K. and Italy to replace the Air Self-Defense Force’s F-2 jet.

The move is significant as it is a step away from one-sided dependence on the U.S. arms industry and offers a path for Japan to secure autonomy.

However, amid the increasingly severe national security environment brought about by China’s rise as a military power and intensifying competition between the U.S. and China over the application of advanced technologies to defense equipment, it is also true that Japan and the U.S. are facing an urgent need to strengthen cooperation in defense procurement and technologies and ensure the Japan-U.S. alliance’s technological superiority.

Japan should implement a comprehensive strategy of gaining superiority over China in developing emerging technologies and their application to defense equipment, and at the same time, share the technologies and equipment with its allies. It is also necessary to utilize them to form partnerships with developing countries, including helping those nations to escape from being excessively dependent on a particular nation and build their capabilities.

(Photo Credit: Reuters / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Managing Director (Representative Director), International House of Japan,

President, Asia Pacific Initiative

JIMBO Ken is Professor at the Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University. He served as a Special Advisor to the Minister of Defense, Japan Ministry of Defense (2020) and a Senior Advisor, The National Security Secretariat (2018-20). His main research fields are in International Security, Japan-US Security Relations, Japanese Foreign and Defense Policy, Multilateral Security in Asia-Pacific, and Regionalism in East Asia. He has been a policy advisor for various Japanese governmental commissions and research groups including for the National Security Secretariat, the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His policy writings have appeared in NBR, The RAND Corporation, Stimson Center, Pacific Forum CSIS, Japan Times, Nikkei, Yomiuri, Asahi and Sankei Shimbun. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University

View Profile-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

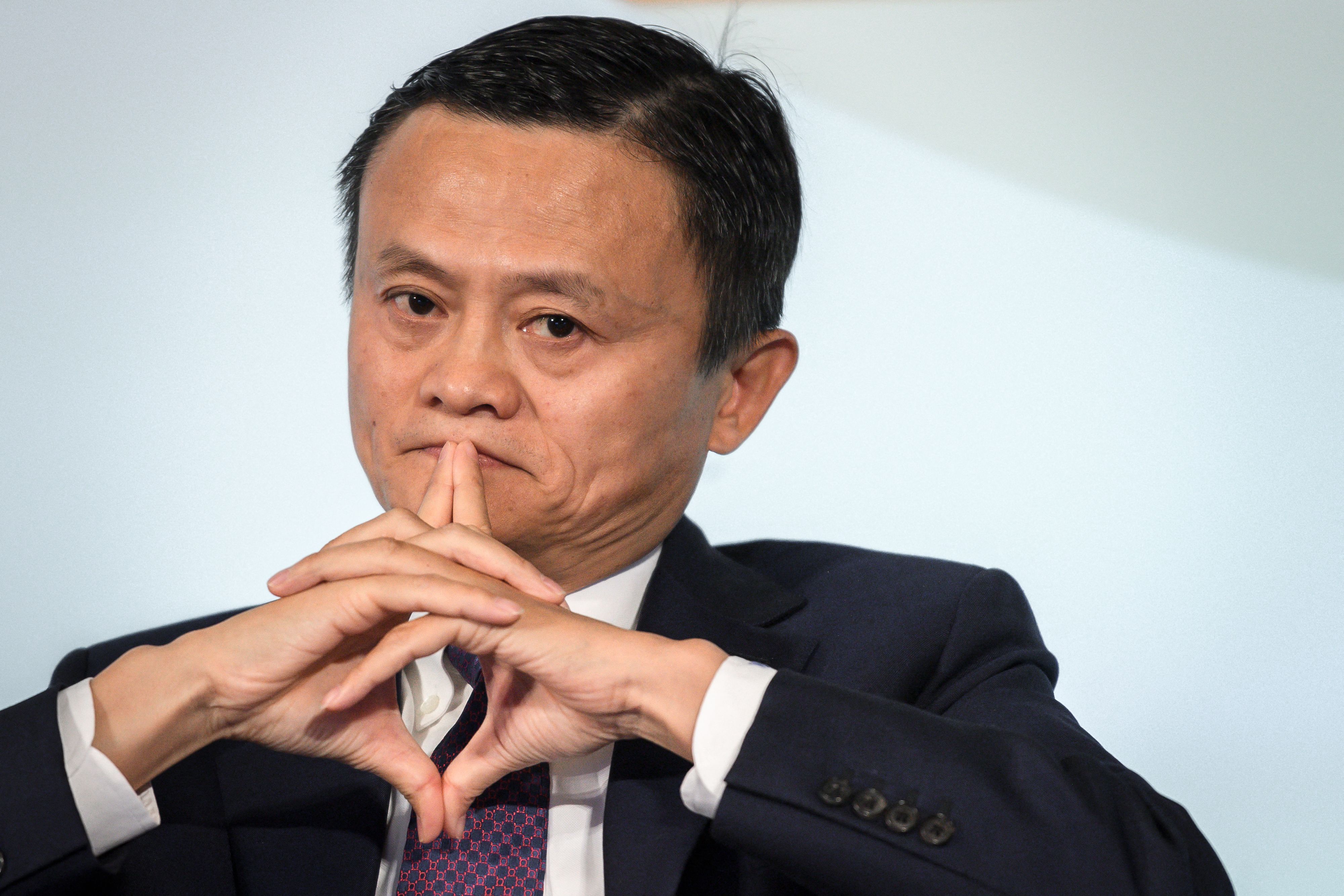

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

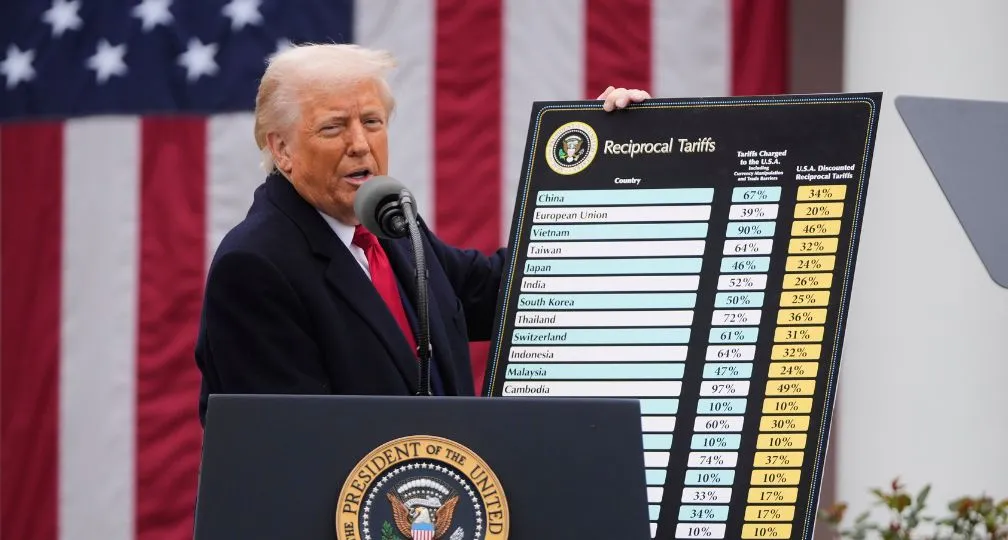

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 After tariffs: Is there a plan to restructure the global economic system?2025.04.03

After tariffs: Is there a plan to restructure the global economic system?2025.04.03