How emerging technologies can bring power to states

While the technologies are anticipated to largely change how militaries, economies and societies are operated, many of their social impacts remain unclear, prompting governments to consider what it means to own and use such technologies.

In such circumstances, the United States has been quick to reconstruct its national security and industry policies based on the advance of a series of emerging technologies, exercising power over countries of concern at times and even over allies and friends in certain cases.

There are a number of ways to convert such technologies into power. To offer one perspective on the issue, this article will focus on the use of technologies as hard power and the influence of imaginative power in doing so.

Imaginative power is defined here as the capacity to generate unprecedented systems and strategies within the realm of emerging science and technology, creating a platform for competitive scenarios that stimulate the imagination of other nations and compel them to respond with actions.

Needless to say, it is important that the power is backed with a strong science and technological base to make the systems and strategies feasible.

Looking from such a perspective, in what way have U.S. efforts regarding emerging technologies acted as power in international relations?

U.S. technology strategy

One of the factors that drew people’s attention to American emerging technologies in strategic terms was the Third Offset Strategy advocated by then-U.S. President Barack Obama’s administration from 2014.

The strategy aimed to create asymmetric advantages over adversaries and maintain an overall strategic advantage by concentrating investments on technological fields where the U.S. had seemed overwhelmingly superior — AI, robotics, autonomous systems, cyber, big-data analytics and advanced manufacturing like 3D printing — and adopting a new operational concept based on such technologies.

Such efforts to wield influence over relations with other countries by converting emerging technologies into military power can be seen as the clearest way to utilize technologies.

At the same time, in the field of economy and industry, emerging technologies have been regarded as something that can create new markets or bring reform to market structures.

The Strategy for American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, announced by the U.S. government in October 2018, stated that emerging markets will be driven by advances in a wide range of technologies, including smart and digital manufacturing systems, industrial robotics, artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing, high-performance materials, semiconductor and hybrid electronics, photonics, advanced textiles, biomanufacturing, food and agriculture manufacturing, among others.

Converting such technologies into economic and industrial competitiveness will lead to the formation of hard power just like military applications.

Imagination

It is important to note that the technologies include those that are gradually being applied to society and those that are still in a conceptual stage.

Even AI, whose social application has been advancing dramatically, was included in the Obama administration’s strategy as strategically important technology while it was not sufficiently in practical use, with the U.S. recognizing that not only general AI but also narrow AI remained immature.

On the military front, AI is increasingly expected to make weapons more autonomous and improve the efficiency of operations and organizational management. On the economic and social fronts, it is now expected to change corporate management and administrative structures significantly. Based on such recognitions, not only the U.S. but others countries worldwide began to invest resources competitively in acquiring such capabilities.

QIS is another issue that is quickly coming under the spotlight. Research and development in the QIS field have been focusing on quantum sensing, quantum computing and quantum networks, but they are not in the stage of affecting international politics as hard power. Some government officers have argued that caution should be exercised when making decisions on the practical applications of QIS, especially in the military sector.

However, as the U.S. began to deal with QIS more strategically after the National Quantum Initiative Act took effect in December 2018, and with China already having been focusing on QIS, competition between Washington and Beijing on the use of QIS accelerated.

The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden began multifaceted cooperation with its allies to advance research on the technology.

The U.S. took the lead also in the field of QIS to show future images of military and industrial applications, effectively forcing other countries to join the new stage of technological competition and cooperation.

Reality and image

As a matter of fact, there have been many cases of a state with new technology gaining a first-mover advantage and other countries catching up.

However, when examining past patterns of technological competitions, it becomes evident that competitions centered on strategic imaginative power differ from those revolving around proven technology.

An example of competition over proven technology is nuclear weapons. After the U.S., which preceded others in developing nuclear bombs, dropped those bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, other countries became strongly aware of the significance of nuclear weapons, resulting in an accelerated nuclear arms race.

Another competition came after it was proved in the Gulf War that the networking of U.S. forces backed by the development of information technology brought about significant improvement in military strength, and other countries moved to imitate the strategy.

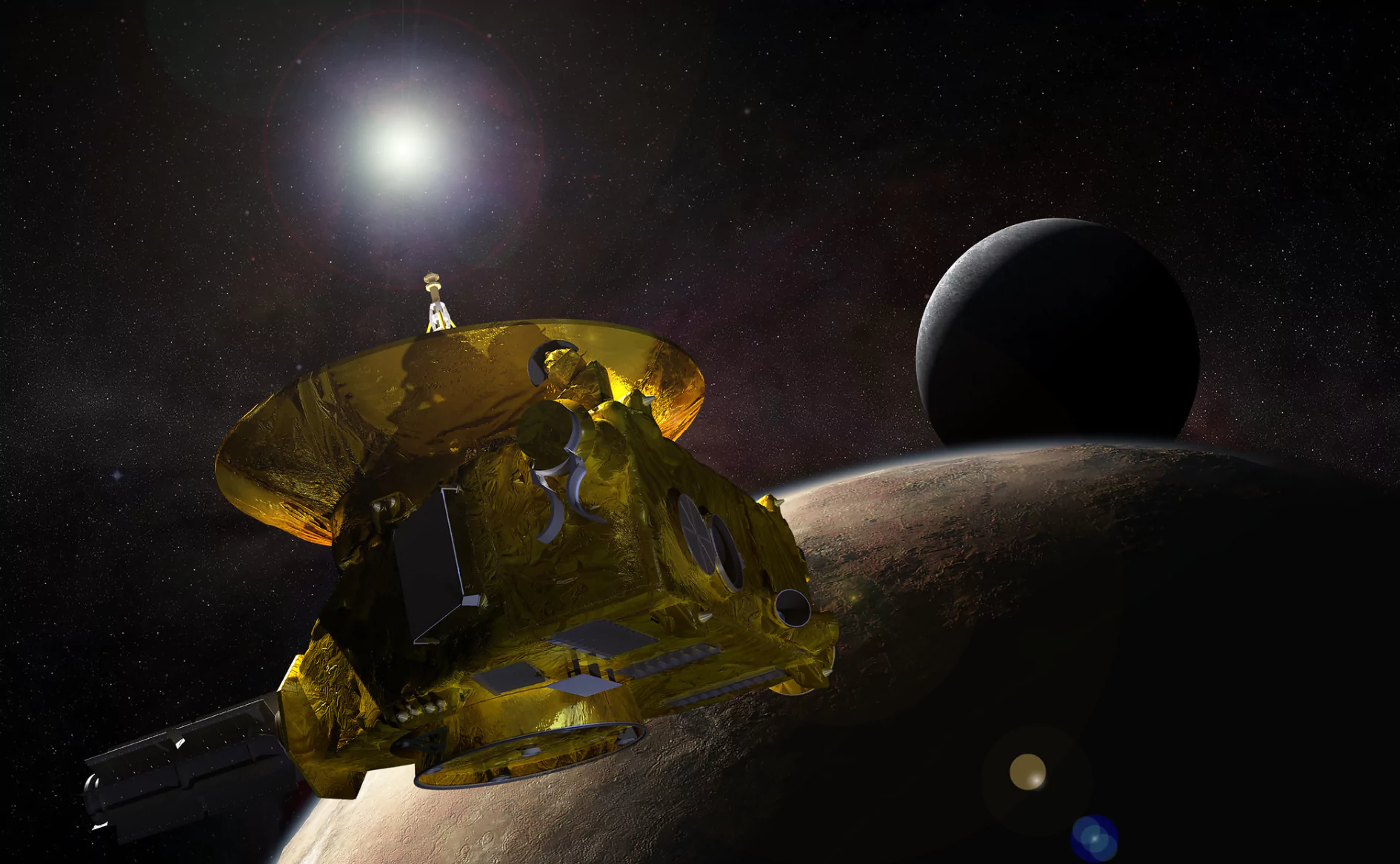

On the other hand, a past example of a state affecting other countries by using technology and imaginative power is the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) announced in 1983 by then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

The SDI, a program that was designed to shoot down intercontinental ballistic missiles with missiles and lasers deployed in space, was nicknamed the Star Wars program, with many physicists, and even officials, casting strong doubt over its feasibility.

Even so, the SDI is said to have led to a backlash as well as a change in the diplomatic stance of the Soviet Union, and had considerable effects on other countries by encouraging allies to join the program through initiatives such as joint research projects.

Today’s race over emerging technologies resembles the SDI in a way that competition is escalating without the practicality of the technologies being clearly established.

However, the U.S. strategy deriving from imaginative power doesn’t necessarily influence other countries as intended.

As for the Third Offset Strategy, the U.S. apparently aimed to maintain an asymmetrical technological advantage in such areas as AI and space.

But while the strategy worked to stir other countries’ imaginative power, forcing them to respond by imposing costs, it actually led China to swiftly catch up on technological development, making the U.S.-China competition increasingly symmetrical.

Exercising imaginative power doesn’t always lead to results that match what was imagined, as they are also affected by power balance among countries and their interests.

Strategic imagination

The U.S.’ strategic imagination over emerging technologies was often regarded as being unclear on how to use them. Sometimes basic research and social applications are conducted simultaneously, and such characteristics of emerging technologies force other countries to take responsive measures.

When considering today’s international relations with such technological circumstances, the next question is whether such imagination can become a power for other countries as well.

As international competition over emerging technologies becomes increasingly symmetric, it is important to focus on how countries like China and Russia will or can move from the stage of catching up to one of trying to influence other countries through innovative ideas.

Yet, it is widely recognized that Washington’s political systems and liberal culture are behind its imaginative power, and the U.S. has a plan to materialize imagination, like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

If that is the case, it would not be easy for authoritarian regimes like China and Russia to exercise imaginative power over technologies, as the U.S. has done, and construct initiatives to be accepted by other countries.

On the other hand, if China is to have imaginative power regarding emerging technologies, it would not be something similar to that of the U.S. It is necessary to closely watch the unique political, cultural and systematic effects it brings about.

What Japan needs to do

Then what can or should Japan do?

The first thing to note is that the importance of technological strategy to create new markets has often been discussed in Japan as well.

The Cabinet Office adopted the management model of DARPA, which led to the implementation of the Impulsing Paradigm Change through Disruptive Technologies (ImPACT) program.

However, ImPACT failed to bring sufficient achievements and has received much criticism.

If the failure of the program is attributable to Japan’s cultural and social structure, there may be many challenges to overcome.

Still, Tokyo needs to continue working to identify fields in which it can exercise imaginative power and areas in which it can’t, based on its strategy.

Efforts to predict other countries’ imagination and build a basis to catch up won’t be wasted, at least.

In order to do so, Japan must keep on exploring the source of its own imaginative power.

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

SAITOU Kousuke is a professor at the Faculty of Global Studies, Sophia University, Japan. He received his Ph.D. in International Political Economy from the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Japan. Prior to joining Sophia University to teach international security studies, he was an associate professor at Yokohama National University, Japan. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Faculty of Global Studies, Sophia University

View Profile-

U.S. LNG and Japan's Sea Lanes: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.03.03

U.S. LNG and Japan's Sea Lanes: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.03.03 -

Attack on Iran: What Comes Next for the Gulf & The Oil Crisis?2026.03.02

Attack on Iran: What Comes Next for the Gulf & The Oil Crisis?2026.03.02 -

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27 -

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29