‘Offensive’ and ‘defensive’ diplomacy: Managing ties with China

In October, China hosted the third round of the Belt and Road Forum. Leaders from many developing countries participated, but there were fewer heads of state from Europe in attendance. Also, the total number of participating leaders had dropped from the previous rounds.

Turning our eyes to the Japan-China relationship, this has been stagnant for the last year, shadowed by issues including the arrest of a Japanese businessman and the release of treated radioactive water from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

Bilateral ties have stalled, with few visits and little communication between high-level officials from the two countries.

What is happening regarding Chinese diplomacy? How can Japan respond to it?

Xi’s diplomatic offensive

After the 20th National Congress of the CCP, in October last year, Chinese diplomacy became even more focused on balancing between “offensive” and “defensive.”

“Offensive” diplomacy refers to China competing against the United States and trying to take its place as a superpower in the global community. This form of Chinese diplomacy seeks to exert influence — by using coercive measures at times — and make other countries accept Chinese values.

In 2017, Xi said, “The Chinese nation has stood up, grown rich and is becoming strong.” His remark indicated that the CCP rule would be able to make China a “strong country.”

Its diplomacy also became “offensive,” strongly pursuing strength in foreign relations.

Under the Belt and Road initiative launched in 2013, China provided assistance to many developing countries without any political conditions, and created friendly ties with them.

Beijing managed to include the phrase “building a community of shared future for mankind” — Xi’s signature concept — in bilateral documents with developing countries and United Nations resolutions, in an effort to give the impression that the Chinese terminology was accepted in the international community.

China proposed its global initiatives on development, security and civilization, and called for “true multilateralism” in an attempt to replace the U.S. in the world’s leadership position.

Such aggressive diplomacy continued this year.

In March, an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia to normalize their ties was made in Beijing, indicating China’s rising influence in the Middle East.

The country sent a special envoy to Europe in May to show its willingness to help reach a political settlement to the Ukraine crisis.

Xi attended a summit of the BRICS countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — in August, where the leaders agreed on expanding the group’s members. In his statement at the summit, Xi advocated reform of global governance.

These activities are listed as achievements of Chinese diplomacy and contributions to realizing the concept in China’s white paper “A Global Community of Shared Future” issued in late September.

Diplomacy on the defensive

On the other hand, China is facing the need to be on the defensive, managing its relationship with advanced economies like Japan, the U.S. and Europe so as to maintain economic growth.

After Beijing adopted reform and opening-up policies in the 1980s, the role of diplomacy was defined to create favorable international relations so that China could focus on growing its economy steadily.

However, the National Congress of the CCP in October last year did not mention that China’s diplomacy in the past five years had produced circumstances favorable for economic growth.

Chinese diplomacy in recent years, dubbed “wolf-warrior diplomacy,” has led to deterioration of ties with industrialized countries.

Chinese products and companies were excluded from the European markets, and science and technology exchanges between China and Western countries began to be restricted.

It has become hard to say that Chinese diplomacy is providing an environment favorable for economic development.

The CCP has suffered from a dilemma that the more the economy grows, the more political and social system reforms are necessary. It also felt that its status as the ruling party was being threatened.

Xi has put more emphasis on security, even if it sacrifices economic development somewhat. However, China still needs economic development, and Xi also repeatedly stresses the need to balance between this development and security.

Boosting economic ties with the U.S. and other advanced economies and gaining access to their technologies are necessary for the Chinese economy to continue to grow. This means that Beijing needs to be defensive about its diplomatic relations to prevent the ties from deteriorating.

Immediately following the party congress last year, Xi attended the Group of 20 summit and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) leaders’ meeting, where he spoke with participating leaders including U.S. President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, all with smiles.

China’s relationship with Australia, which became strained after Canberra called for an international investigation into the origins and spread of COVID-19, began to improve last fall as ministerial-level talks between the two restarted.

Communications continue

While Beijing is trying to balance between “offensive” and “defensive,” Washington continues to communicate with officials there.

The two countries’ relations cooled down after a U.S. military fighter jet shot down a suspected Chinese spy balloon over the Atlantic in February. In May, however, Wang Yi, CCP politburo member and China’s top diplomat, held talks with U.S. national security adviser Jake Sullivan in Vienna, and Chinese Commerce Minister Wang Wentao visited the U.S just after.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken traveled to Beijing in June, followed by U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s visit in July.

In the U.S. domestic context, U.S. Congress is dominated by a tough stance toward China, with Beijing described as “the only punching bag” for U.S. lawmakers.

It is also difficult for Washington to make compromises regarding China ahead of the U.S. presidential election next year.

Washington has never stopped criticizing Beijing over human rights issues and Taiwan, and it is strengthening economic sanctions against China, including semiconductor-related export restrictions.

Still, it has not terminated communications with Beijing.

Blinken had phone talks with Wang, now foreign minister, immediately following Hamas’ attack on Israel last month.

Beijing is also maintaining communications with Washington while taking into consideration a growing domestic sentiment of seeing the U.S. as a rival on an equal footing.

When Blinken visited Beijing in June, his meeting with Xi saw a seating arrangement that was quite unusual in terms of diplomatic protocol, with Xi at the head of the table and Blinken and Wang sitting on both sides facing each other.

Beijing set a stage for dialogue by deliberately stressing that Wang is Blinken’s counterpart and that China stands shoulder to shoulder with the U.S.

The U.S. and China are trying to manage their relationship by continuing to communicate while acknowledging that their relationship will not improve dramatically in the near future.

On Nov. 15, Biden and Xi held four hours of talks just outside San Francisco on the sidelines of the APEC summit.

Japan-China relations

Then how does Beijing see its relationship with Tokyo?

Japan and China also began working to improve their ties following the Kishida-Xi meeting in November last year in Bangkok on the sidelines of the APEC summit.

In February, then-Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi held telephone talks with then-Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang, which were followed by a meeting between Hayashi and Wang during their visit to Germany a few weeks later.

In the same month, Japan and China held their first security dialogue in four years, which discussed sensitive issues between the two countries.

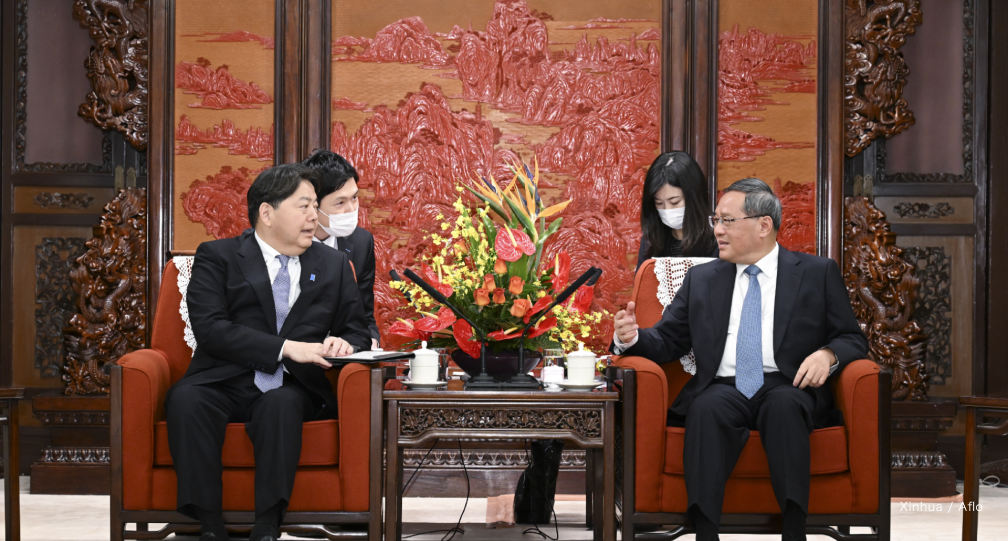

In April, Hayashi visited Beijing, the first time for a Japanese foreign minister to travel to the country in roughly 3½ years.

China lodged a protest against Japan, which chaired the Group of Seven summit in May, over references to Taiwan and other issues related to the country in joint statements issued during the meeting.

However, Beijing must have felt relieved to see that the G7 leaders’ communique referred to the importance of engagement and cooperation with China and expressed an intention not to seek to thwart China’s economic progress and development.

Soon after the G7 summit, Japan and China held a director-general meeting between foreign affairs departments in June. In July, a delegation from the Japanese Association for the Promotion of International Trade met with Chinese Premier Li Qiang, No.2 in the CCP, in Beijing.

The bilateral ties appeared to improve, but a planned visit by Natsuo Yamaguchi — head of Komeito, the junior party in Japan’s ruling coalition — was postponed by Beijing in its response to Japan releasing treated radioactive water in August.

Even after that, China has maintained its stance of working to improve relations with Japan. There was a brief conversation in September between Kishida and Li followed by the High-level Consultation on Maritime Affairs in October.

However, Tokyo and Beijing’s communications have been fewer than those between China and other Western countries. Taking ministerial-level visits as an example, Hayashi’s trip to Beijing was the only occasion for leaders or ministers from the two countries to visit each other since the Kishida-Xi meeting in November last year.

Japanese people’s sentiment toward China has remained very much negative. A survey conducted by the Cabinet Office on diplomatic affairs shows that the percentage of respondents who feel friendly toward the country has lagged at around 25% in the past decade.

Holding a dialogue with Beijing or visiting the country has huge risks amid severe negative public sentiment toward China, and high-ranking Japanese officials cannot be proactive about engaging with China.

Many researchers and businesses are also becoming reluctant to visit the country after the detention of a Japanese businessman in March and China’s revised counterespionage law in July.

On the issue of treated radioactive water, the two countries’ governments have failed to communicate sufficiently, and Beijing has strongly condemned Japan.

Kishida explained the issue to South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol in person, and communications were made between Japanese and South Korean foreign ministers on the issue.

Japan also accepted a visit by South Korean experts to the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

However, no such actions or communications have happened between Japan and China.

In September, the Chinese government claimed it was not taking part in the monitoring programs of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) because it had not been invited by Japan.

The Japanese government’s stance is that it is not in a position to invite China to join the IAEA’s monitoring program.

In October, China participated in the monitoring carried out by the IAEA under a bilateral arrangement between Japan and the IAEA.

Beijing is struggling to find a balance between building ties with Japan and achieving Xi’s goal of making China strong. It doesn’t want to complicate relations with Japan as this could worsen its economy.

Many officials from China’s local governments and companies continue to visit Japan in an effort to attract Japanese companies to invest in the country.

At the same time, China has been conducting a diplomatic offensive, lodging unilateral maritime claims in the East and South China seas, as well as criticizing Japan, a U.S. ally, in an effort to display its international influence.

In September, the Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a paper on the reform of global governance. As part of security issues, the paper urges the Japanese government to respond to the international community’s concerns over the Fukushima water release and also speed up the destruction of abandoned World War II chemical weapons in China.

It seems that Beijing will continue to criticize Japan over the treated water issue in the future.

Dealing with China

The “offensive” aspects of Chinese diplomacy tend to be highlighted in Japan, but it also has the “defensive” aspects of attempting to improve ties with Japan.

Japan should take into account this dual nature of China’s diplomacy and continue to communicate with the country from a strategic perspective.

Japan wants China to become a country that improves its transparency while developing its economy, a country that does not resort to unilateral or coercive measures such as restricting trade or sending government ships to Japan’s territorial waters — a country that will work together for the peace and stability of the region and the wider society.

To help make China such a country, Tokyo must continue communications with Beijing even if there are difficult issues and anti-China sentiment within Japanese society.

In their dialogue, Japan should clearly point out China’s problems, including its self-righteousness and lack of transparency, and call on the country to make concrete improvements.

Negative views on China tend to attract attention and win support in Japan, but it would not be beneficial for Tokyo to become too cautious about communicating with Beijing because of that.

Some in Japan say Tokyo should be careful about having dialogue with Beijing in view of the U.S.-China confrontation, but we must note that the U.S. and China are maintaining high-level communications in spite of their sour relationship.

Even if there are thorny issues, Japan should maintain its stance of communicating with Beijing, managing individual issues and saying what needs to be said.

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on November 14, 2023:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2023/11/14/world/germany-china-strategy/

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

MACHIDA Hotaka is a visiting senior research fellow in Institute of Geoeconomics at International House of Japan. He joined the Institute in October, 2022. Prior to leaving his role in government, he served as a career diplomat in Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2001 to 2022, focusing on Japan-China relations. He studied at Nanjing University in China and Harvard University in the United States, followed by working at Embassy of Japan in China as second secretary from 2006-2008. After that, he was posted in China-Mongolia division in the Ministry and completed the negotiations with China over the issues of launching the “High-Level Consultation on Maritime Affairs” as well as finalizing the “Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR)” agreement. He also worked in Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) division in the North America Bureau in the Ministry leading the negotiations with the US on SOFA-related issues. He was counsellor in the Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations (2017-2020) and Embassy of Japan in China (2020-2022) covering the Security Council reform and Japan-China economic relations respectively. He holds a M.A from the Graduate School of Arts and Science at Harvard University, and a Bachelor from Law Faculty at Tokyo University.

View Profile-

DOGE Shock and Crisis in U.S. Credibility2025.07.14

DOGE Shock and Crisis in U.S. Credibility2025.07.14 -

India’s Strategic Autonomy in a Trumpian World2025.07.11

India’s Strategic Autonomy in a Trumpian World2025.07.11 -

Air superiority vs. air denial: Redefining U.S. airpower strategy2025.07.09

Air superiority vs. air denial: Redefining U.S. airpower strategy2025.07.09 -

The Lessons of the Nippon Steel Saga2025.07.08

The Lessons of the Nippon Steel Saga2025.07.08 -

Unchecked and unbalanced: The future of U.S. economic policymaking2025.07.07

Unchecked and unbalanced: The future of U.S. economic policymaking2025.07.07

The Lessons of the Nippon Steel Saga2025.07.08

The Lessons of the Nippon Steel Saga2025.07.08 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 India’s Strategic Autonomy in a Trumpian World2025.07.11

India’s Strategic Autonomy in a Trumpian World2025.07.11 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09