What the Israel-Hamas war means for U.S. grand strategy

Project Researcher, Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Tokyo

The unprecedented attack on Israel by Hamas militants on Oct. 7, which has been compared by some to al-Qaida’s Sept. 11 attack on the United States in 2001, was sure to have an indelible impact on the geopolitics of the Middle East, including the future trajectory of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

This assault, however, may have far-reaching consequences beyond the region, including for U.S. allies located in geopolitical front-line areas such as Japan. The United States has been engaged in a decadelong effort to shift its strategic attention from the Middle East to great power competition with China and Russia since the administration of former U.S. President Barack Obama. The potential normalization of diplomatic ties between Israel and Saudi Arabia, brokered by the United States, was seemingly a fruition of Washington’s steady effort to produce a favorable strategic environment in the Middle East.

But some observers suggest that this long-term goal to fundamentally shift America’s strategic orientation could now be in jeopardy. The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden appears to be fully aware of the global repercussions of the outcome of the Israel-Hamas war. This ongoing conflict may disrupt, if not totally derail, the underlying direction in U.S. grand strategy to finally focus its defense on great power competition. China, and especially Russia, could, in fact, exploit the hiccup caused by the crisis in the Middle East that Washington was unprepared for, a move that could inadvertently become a destabilizing factor both in the western Pacific and Europe. What does this ongoing crisis in the Middle East mean for long-term U.S. strategy?

Exiting the Middle East

U.S. national security adviser Jake Sullivan observed just a week prior to the Oct. 7 attack that the Middle East “is quieter today than it has been in two decades.” Washington’s strategy to proactively scale back its commitments in the Middle East to reallocate its resources and attention to great power competition, notably in the Indo-Pacific region, seemed to have borne fruit. The process of shifting strategic priorities, however, did not happen overnight.

The 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy (NDS) that first articulated the United States’ intention to prioritize great power competition by drastically pivoting away from counterterrorism served as a critical juncture. However, it was, in fact, the Obama administration that pursued a long-term strategy to reconcile domestic economic resilience and great power relations by cultivating U.S. national power. Obama sought to “rebalance” Washington’s focus to the Asia-Pacific while devoting fewer resources to the Middle East, as demonstrated by the 2009 Afghan Surge — the ordering of 30,000 additional troops to Afghanistan — that had been designed to pave the way for an eventual withdrawal from the country.

In other words, the past decade saw the United States gradually implementing the necessary changes to shift the nation’s strategic priorities — from counterterrorism to great power competition. China’s increasing assertiveness in the western Pacific and the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 had urged the Obama administration to shift its attention more toward great power competitors — namely, both countries. However, to realize this strategic reorientation, especially in changing the way the U.S. military fights — which includes necessary bureaucratic overhauls and budgetary reprioritization — was certainly no easy task. The 2018 NDS illustrated a drastic change in the United States’ global force posture by illuminating Washington’s reprioritization to focus on peer competitors by shifting from the so-called “Two War Construct” — that the U.S. should be able to fight two simultaneous wars with regional powers.

But as the effort to withdraw from Afghanistan since the 2009 Afghan Surge, which took more than a decade, suggests, drastically reducing U.S. commitment in the broader Middle East is not a straightforward endeavor. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in the summer of 2021 finally marked the end of an era — since 2001 — in which counterterrorism in the broader Middle East dominated the imagination of the U.S. national security establishment. The project to shift U.S. strategic orientation toward great power competition in the Indo-Pacific region, which has lasted more than a decade as well, is unlikely to be reversed overnight. Nevertheless, an unintended escalation to a regionwide war could pull the United States back into a region that it has sought to extricate itself from for over a decade, even if it is temporary. Israel’s vow to eradicate Hamas, absent a clearly stated political endgame, concerned some observers who highlighted how an ill-defined application of military power could instead inadvertently harm its own strategic, political and moral standing. Given the sheer scale of the Hamas attack, some sort of retaliatory action was inevitable. The Biden administration has been making vital efforts to shape the Israeli response against Hamas in order to prevent a regionwide conflagration so as to minimize its impact on Washington’s overall long-term strategy.

The U.S. response

The U.S. response to this unfolding crisis in the Middle East has mainly focused on escalation control and limiting the scope of the war by influencing Israel’s military response. The duration and intensity of this operation matters in minimizing the risk of the war eventually provoking a regional crisis. How the Israeli military operation in Gaza is fought carries a large weight in determining the risks of unintended escalation and the overall trajectory of the war. Israel, Iran and the United States have all been engaged in what is often referred to as a “shadow war.” They have been taking cautious steps to prevent covert skirmishes from being exposed and leading to direct military confrontation as a form of escalation control. They do so by denying their involvement or even collusion with their opponent in this endeavor. In fact, regional players in the Middle East, including the United States, have proactively been following these crucial steps in escalation control to proactively deny Iran’s direct role in the Oct. 7 attack.

There are plausible reasons to believe that Iran and Hezbollah, its proxy in Lebanon, are unwilling to enter the war as belligerents, which would most likely turn the war into a regional conflict. Lebanon’s economic crisis suggests how initiating an all-out war with Israel by opening a second front would be a politically costly move for Hezbollah, a Shiite militia group. Also consider Iran’s measured response after the target-killing of Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the elite Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps during the time of the Trump administration. While this bold targeted strike on the mastermind of Iran’s proxy warfare triggered fears of war, Iran’s calculated retaliatory strikes underscored Tehran’s clear desire not to directly confront the United States in an all-out war. Israel’s military response, however, may inadvertently undermine these preexisting efforts for escalation control. First and foremost, the absence of a clearly defined and achievable political endgame in Israel’s military response to Hamas increases the risk of a protracted war. Israel’s stated goal of eradicating Hamas, for example, would not necessarily result in a political victory for Israel without a feasible post-war plan that brings a certain degree of stability to the Gaza Strip.

In addition, while the desire for revenge often dictates wars, the use of military force without any precise political ends may not only be self-defeating but also raises serious ethical questions. Moreover, Gaza is a densely populated environment in which a ground incursion entails intense urban combat. Urban warfare is fought under notoriously demanding settings that would most likely result in a deadly, protracted and costly campaign that would inevitably involve massive civilian casualties and further deteriorate the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. As a result, it could trigger public unrest in regional states that could ignite further disorder, including the erosion of Israel’s recent diplomatic gains from the series of rapprochements with several Arab states. In short, a protracted urban campaign in Gaza may result in an unintended escalation of the war.

The Biden administration, therefore, has primarily been focused on assisting Israel in setting a feasible political goal in this campaign and helping shape the way the war is being fought through a prudent application of military force. The United States’ own experience in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks offers Washington a compelling role in guiding Israel’s response to the Hamas attacks on Oct. 7. This endeavor seems to have produced mixed results so far, yet its outcome will play a key role in shaping the trajectory of the Israel-Hamas war.

Great power competition

The United States’ response to the Israel-Hamas war has basically been an attempt to prevent the war from derailing its grand strategy to focus on great power competition. At the same time, twin challenges — namely the crisis in the Middle East and a stalemate in the war in Ukraine — have illuminated the inherent challenge in bridging the gap between the planning and implementation of a grand strategy — the very hurdle the Biden administration is currently facing. In a speech on Oct. 20, Biden underscored the importance of assisting both Ukraine and Israel amid diminishing appetite in the U.S. Congress for renewed support for Ukraine.

However, instead of pursuing a decisive victory on all fronts, there is a need to identify “the culminating point of victory” as Prussian general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz puts it in his book “On War” while also acknowledging the growing interdependence among different theaters. As the Ukrainian counteroffensive reaches a stalemate, it is crucial to consider a feasible political solution, including an armistice negotiation, by determining the culminating point of victory that offers an acceptable political and military endgame for the protracted war. The same thing could be said about the Middle East.

“Great power competition” is merely a description of the state of international relations and is not a strategy in itself. An effective grand strategy requires a constant assessment of the ends and means amid finite resources. This art of grand strategy has become even more salient as Washington contends with great power rivalry amid increasing demands for austerity. Washington’s overall response to the Israel-Hamas war presents a critical juncture for the United States to recalibrate its long-term grand strategy by also setting realistic goals for respective crises. On the other hand, for U.S. allies including Japan, the war in the Middle East may serve as a key opportunity to reaffirm the vital need to proactively bolster national defense, including strengthening the U.S.-Japan Alliance to keep any lapse in long-term U.S. strategy from being exploited by great power competitors in the western Pacific.

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on January 15, 2024:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2024/01/15/world/israel-hamas-us-strategy/

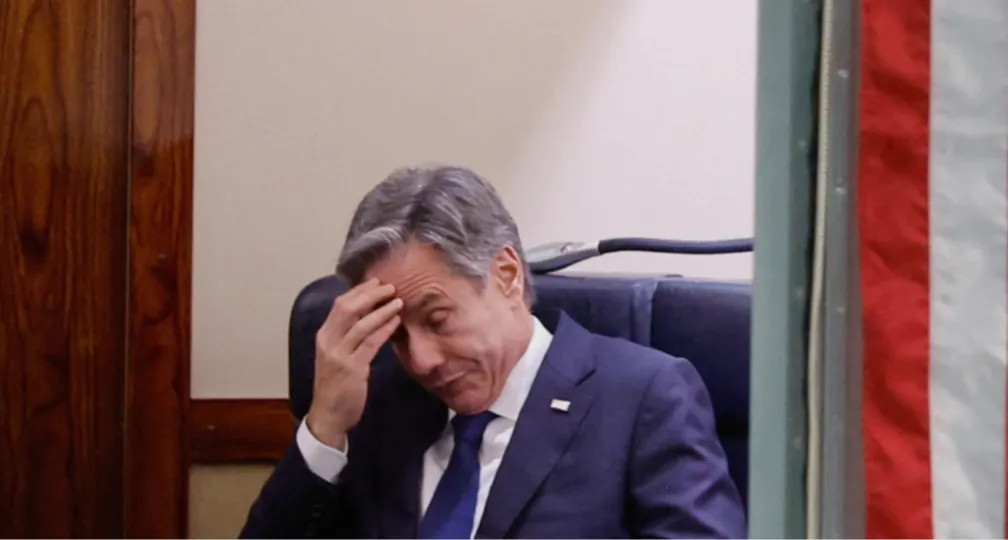

(Photo Credit: Reuters / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07