Both U.S. presidential candidates’ security strategies raise concerns

Author: Kuniharu Kakihara

Faced with two wars, one in Europe and the other in the Middle East, as well as rising tensions in East Asia, the United States’ limited resources means that it will be difficult for either candidate in the upcoming election to drastically alter the current trajectory.

However, the nominees’ divergent policy orientations and leadership styles give rise to different sets of concerns.

American allies fear that a Trump 2.0 administration could damage relationships that are currently on a firm footing — with former President Donald Trump vowing to pull the U.S. out of the conflict in Ukraine and end the war.

If Vice President Kamala Harris wins, continuity with President Joe Biden’s security policies is expected, though her relative lack of foreign policy experience is causing some unease.

Whoever becomes president, their strategic leadership will be put to the test from day one.

U.S. security strategy

America’s security stance has continuously evolved, driven by the policy orientations and leadership of different presidents, with a regular redrawing of the strategy’s focus, military posture and use of military power.

While the Cold War-era “two-front” strategy of large forces deployed in Europe and Asia has been maintained, its scale has been gradually reduced. During the administration of Bill Clinton in the 1990s, the “two major theater wars” strategy was adopted, aiming for the U.S. to have the capacity to fight and win two major regional conflicts simultaneously.

However, toward the end of Clinton’s presidency, a gap between force structure and available resources became an issue, leading to the beginning of a strategic shift toward addressing the rise of China.

This shift was interrupted by the 9/11 attacks in 2001 and the focus quickly turned to the war on terror, delaying further adjustments to the force posture.

However, the prolonged nature of this war, combined with the 2008 financial crisis, led President Barack Obama to reduce U.S. military engagement abroad. In 2010, the Obama administration explicitly moved away from the assumption that the U.S. must be able to win two overlapping regional conflicts. Although Obama promoted the “pivot” toward the Asia-Pacific, the deteriorating situation in Afghanistan and Syria prevented any major redeployment of American forces under his presidency.

Trump later reversed this trend, increasing military spending and explicitly identifying China as the United States’ primary strategic competitor, adopting a “one-front” strategy. Despite this, no significant changes to Washington’s military posture were adopted.

It was not until the Biden administration that the U.S. completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan and fully shifted its strategic priorities toward addressing China’s growing military power. Biden also advanced the concept of “integrated deterrence,” emphasizing stronger collaboration with allies and partners.

In the midst of these changes, Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. While avoiding direct intervention, the Biden administration has provided hefty military support to Kyiv. In parallel, the U.S. has also deployed additional carrier strike groups to the Middle East, where tensions are running ever-higher.

In East Asia, China continues to expand its military power, including its nuclear arsenal, while engaging in territorial expansion in the East and South China Seas. The Chinese Communist Party has openly declared its goal of “reunifying” Taiwan and increased military pressure on the island.

Should an accidental U.S.-China conflict occur in East Asia, the military linkage between China and Russia could prompt Moscow to expand its war in Ukraine, while anti-U.S. states such as Iran might seize the opportunity to attack Israel. Such a scenario risks escalating into a global conflict.

Given this complex strategic environment, the bipartisan Commission on the National Defense Strategy released a report in July 2022 calling for a review of the National Defense Strategy released that same year. The commission assessed that the U.S. military is not prepared to handle simultaneous conflicts in Europe, the Middle East and East Asia — and recommended a return to a strategy that ensures resources and plans for fighting multiple wars at the same time.

However, implementing this recommendation would require a dramatic increase in defense spending, which seems unrealistic given Washington’s fiscal limitations and the lack of domestic political support.

The key challenge for the next administration’s security strategy will be how to enhance the U.S. military’s posture to deter China while also addressing threats in other regions, which includes providing a clear plan for resource allocation. Stability in the three key regions will depend on how anti-U.S. forces perceive America’s willingness to intervene and maintain the military balance.

Harris and integrated deterrence

If Harris wins the election, she will likely maintain Biden’s “integrated deterrence,” which also relies on the forward deployment of American military forces.

Harris has opposed pursuing a massive military buildup. Instead, she is likely to continue focusing on deterrence through asymmetric means, such as the ongoing “Replicator” program, which aims to offset China’s quantitative advantage by deploying large numbers of small drones known as “all-domain attritable autonomous systems.”

But when it comes to China’s nuclear arsenal, if the U.S. does not maintain its current superiority, the risk is that Beijing achieves nuclear parity. Should a Harris administration fail to offer an effective solution to China’s nuclear challenge and if China perceives the U.S. as accepting a state of mutually assured destruction, this could embolden Beijing’s belief in the “stability-instability paradox.” Chinese leaders might thus think that they could prevent U.S. intervention in a potential Taiwan conflict.

In addition, Harris is likely to aim for deescalation in Ukraine and the Middle East, avoiding direct military involvement while continuing military aid. However, given the possibility of a Republican majority in Congress, the outcome of the election could lead to roadblocks in these efforts.

Trump wants America first

If Trump prevails, he is expected to pursue his “America First” policy by strengthening the U.S. military’s superiority with a focus on strategic competition with China. While Trump has expressed a desire to end the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, his plans for handling the conflicts if peace negotiations fail remain unclear.

There is also the risk that U.S. adversaries, who benefit from instability and chaos, may take actions that catch a Trump administration by surprise.

A major concern with the Republican candidate’s strategic vision is the lack of a clear framework for when and how to use military power — including allies’ forces — to resolve conflicts and maintain order.

While Trump’s unpredictability may have a deterrent effect on irrational actors such as North Korea, any hesitation to use force could weaken that deterrent over time. Furthermore, Trump’s repeated remarks that Taiwan should pay for its defense and that the island has stolen the semiconductor business away from the U.S. raise doubts about whether a Trump administration would reconsider military aid to Taiwan.

Japan’s response

Regardless of who becomes president, security strategies will remain focused on deterring China. It is crucial for Japan to work toward strengthening the relationship between the next prime minister and the U.S. president, ensuring that the grid-like alliance network built between Biden and former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida remains intact.

This includes reinforcing communication channels at all levels and candidly conveying Japan’s concerns and perspectives. It is also vital for Tokyo to take an active role in maintaining regional alliance networks to prevent China from exploiting any vulnerabilities.

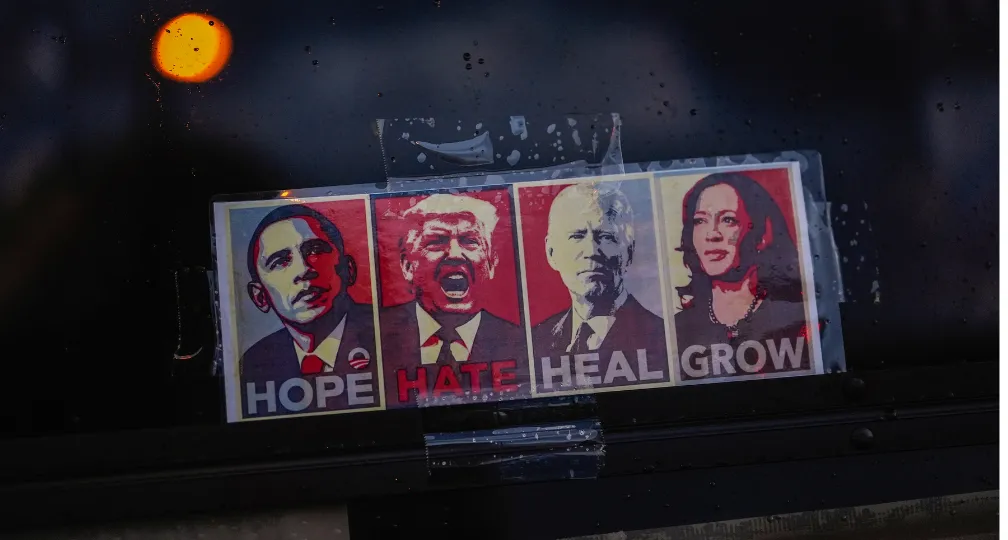

(Photo Credit: Shutterstock)

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on October 29, 2024:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2024/11/01/world/us-elections-trump-harris-security-concerns/

Author

Kuniharu Kakihara

Kuniharu Kakihara, a retired lieutenant general of the Air Self-Defense Force, is principal research director at the National Security Institute, Fujitsu Defense & National Security.

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

-

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25 -

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 -

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma2025.06.11 -

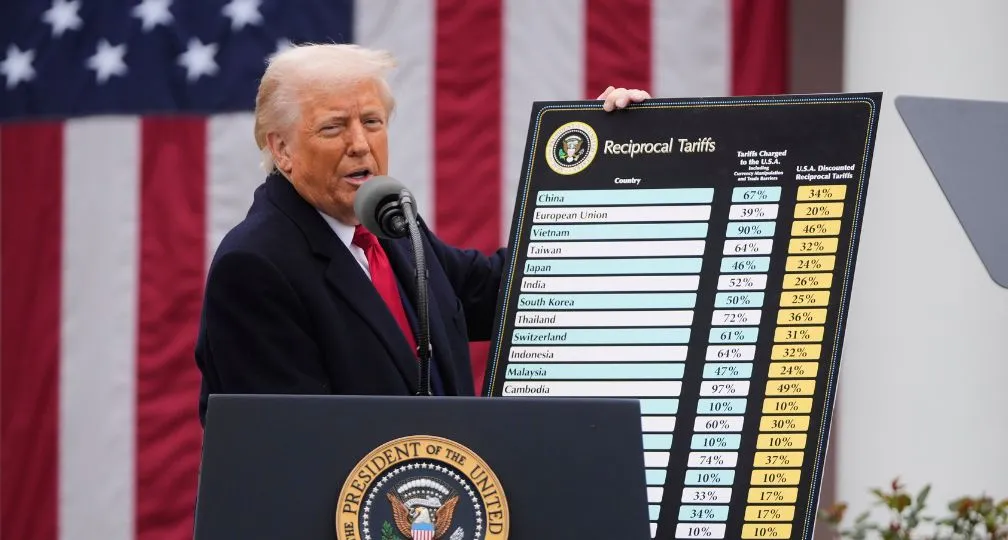

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31

The Courts Rule Trump’s April 2 Tariffs Illegal – What Happens Next?2025.05.31 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.05.29

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11

The Big Continuity in Trump’s International Economic Policy2025.06.11 Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27

Trade, capital flows, and the new focus on “global imbalances”2025.05.27 Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06

Trump’s Major Presidential Actions & What Experts Say2025.02.06 The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition2024.02.09 From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25

From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity?2025.06.25