A Dangerous Confluence: Introduction

The far-reaching impacts of disinformation, from societal polarization to the role of technology in its spread, present substantive challenges to democratic states. Given the urgency of this issue, three early career researchers from the Europe and Americas group within the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) conducted a six-month research project between January and June 2024 on the relationship between democratic backsliding and disinformation. Our research consists of three select case studies, Hungary, the United States, and the United Kingdom due to the relative degrees of democratic backsliding in each, to analyze the current state of disinformation in each country, their policy responses, and the impact of disinformation on the three countries. We conclude the report by outlining the state of disinformation in Japan, and lay out five policy recommendations that may be applied to Japan based on the three main case studies.

Hungary was selected as the country in Europe that has experienced among the most democratic backsliding since 2010, transitioning from a liberal democracy to an electoral autocracy, [1] despite its successful democratization after the collapse of the communist rule. In this chapter, we introduce the example of the Orbán administration and its political party’s increasing influence over the media and the resulting spread of disinformation in the Hungarian context. The United States was selected as a major liberal democracy vulnerable to democratic backsliding due to its domestic political environment. A combination of distrust towards institutions and the media, coupled with a lack of regulation of social media platforms, has led to the accelerated spread of disinformation. The United Kingdom was selected as a country which has displayed stronger institutional resilience, despite having been susceptible to similar forces of populism and disinformation during the Scottish Independence and Brexit referendum campaigns. However, despite its relatively robust democratic institutions, disinformation continues to pose a threat through what the chapter calls the “engagement trap”. In the final chapter, the authors outline the most prominent recent disinformation campaigns that have spread in Japan, how the state of disinformation in Japan differs from that of the other case studies, and explain how some of the ‘lessons learned’ in the other cases may provide helpful policy recommendations for Japan.

In the remainder of this chapter, we define the key terms we use throughout this report, particularly disinformation and democratic backsliding, and explain why we focused on these issues. We argue that disinformation poses a threat to liberal democratic countries as disinformation corrupts both the democratic institutions and their norms. We identified three key enablers of disinformation, namely, the lack of anti-disinformation policies, distrust of democratic institutions, and political polarization, to assess how each plays a role in a country’s disinformation environment. In the final section, we outline the structure of this report.

The Definition and Purpose of Disinformation

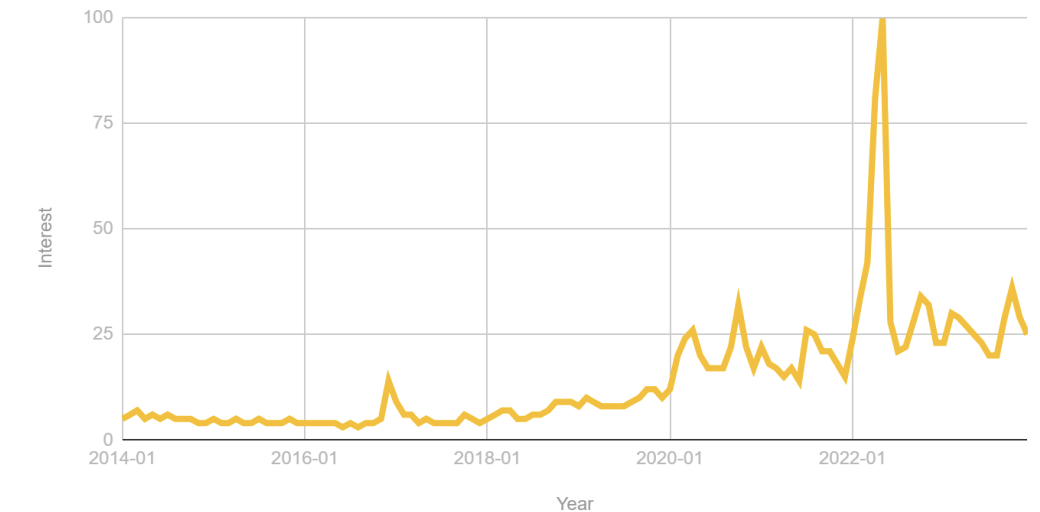

Problems related to “disinformation”, particularly in politics, are far from being exclusively modern issues, and have been especially persistent in certain countries, making it unsurprising that they persist today [2]. The term has gained greater coverage in recent years, and a cursory search on Google Trends shows that its use has grown worldwide since the 2020s. At the same time, the ubiquity of the term has also led to misunderstandings about what it actually means.

For the purposes of this report, we define disinformation as distinct from other forms of information in that it has the intent to mislead people by increasing the likelihood of “false beliefs” to form. [3] In other words, even if an individual is not necessarily deceived by the disinformation, the fact that there was an intent to mislead is sufficient for it to be classified as disinformation.

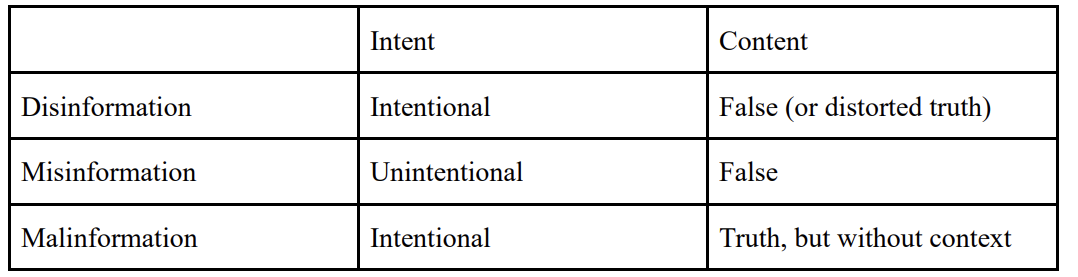

This is in contrast to misinformation which is often used interchangeably with disinformation. On one hand, misinformation distinguishes itself from disinformation in that it has no clear intention to mislead; on the other hand, part of the information remains categorically false which sets it apart from information. [4] Additionally, disinformation differs from malinformation which intends to target and manipulate the image of certain groups and individuals using factually correct information (examples include harassment and hate speech).[5]

Figure 1: Search queries of the term “Disinformation” worldwide  (Source: Created by the authors using data from Google News Initiative [6])

(Source: Created by the authors using data from Google News Initiative [6])

Table 1 summarizes this distinction between disinformation, misinformation, and malinformation by categorizing them based on their intent as well as whether the content is true or false. Thus, the combination of a clear intent to mislead using false or partially false information is what defines disinformation, regardless of whether its consumer is deceived or not. In other words, disinformation is an ideal example of Shakespeare’s line “there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so”. [7]

Table 1: Author’s own summary of disinformation, misinformation, and malinformation based on intent and content.  (Source: Created by the authors)

(Source: Created by the authors)

Disinformation has several key elements that explain its pervasiveness and difficulty to effectively regulate. First, it can spread faster online than the truth. [8] Digital actors including bots can also accelerate the speed at which disinformation spreads more than the people who originally developed the false claim. [9] Cognitively, once misinformation is received and stored in the memory, it can be difficult to replace with correct information, leading to people inadvertently spreading false information even after they have been corrected. [10] Thus, disinformation tries to sow chaos and make people distrustful of the content they see.

The aim of disinformation is not to make people believe in the disinformation itself, but to confuse or sow doubt. For example, the RAND Corporation describes the Russian disinformation strategy as the “firehose of falsehood” where people are bombarded with so many lies that they no longer know what to believe. [11] In other words, disinformation does not necessarily require a strategy or consistency. All it takes is high volumes of disinformation to spread even if the content itself might be simple and crude. [12]

Simultaneously, the content does not necessarily need to be completely untrue. Academics such as Thomas Rid argue that in fact, disinformation could consist of several small lies, making it difficult to say that everything about a claim is false. [13] In sum, this section defines disinformation as a type of information that has the intent to mislead, but one that is not necessarily consistent, and is an ideal tool to sow doubt.

Democratic Backsliding

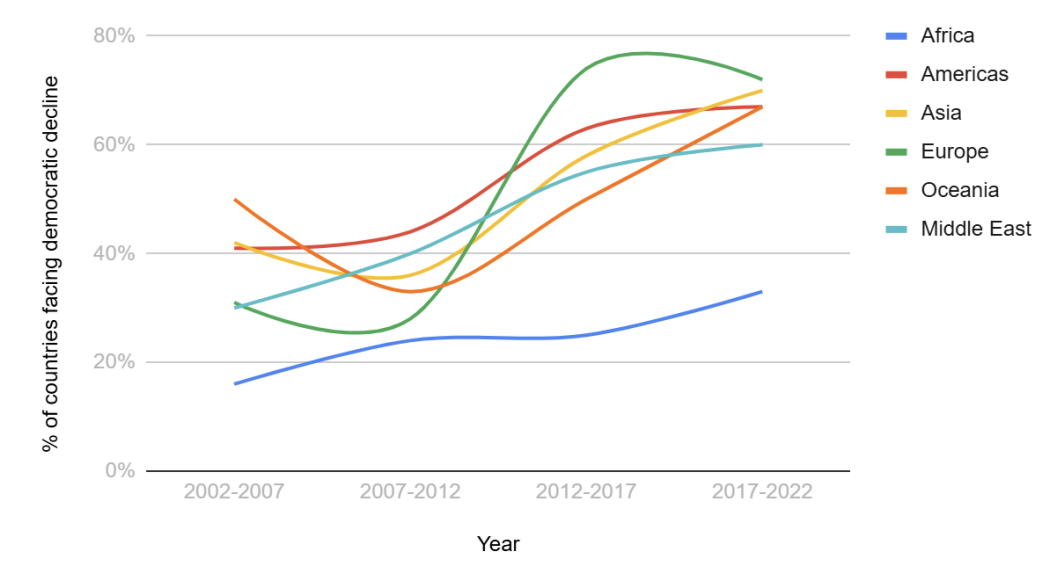

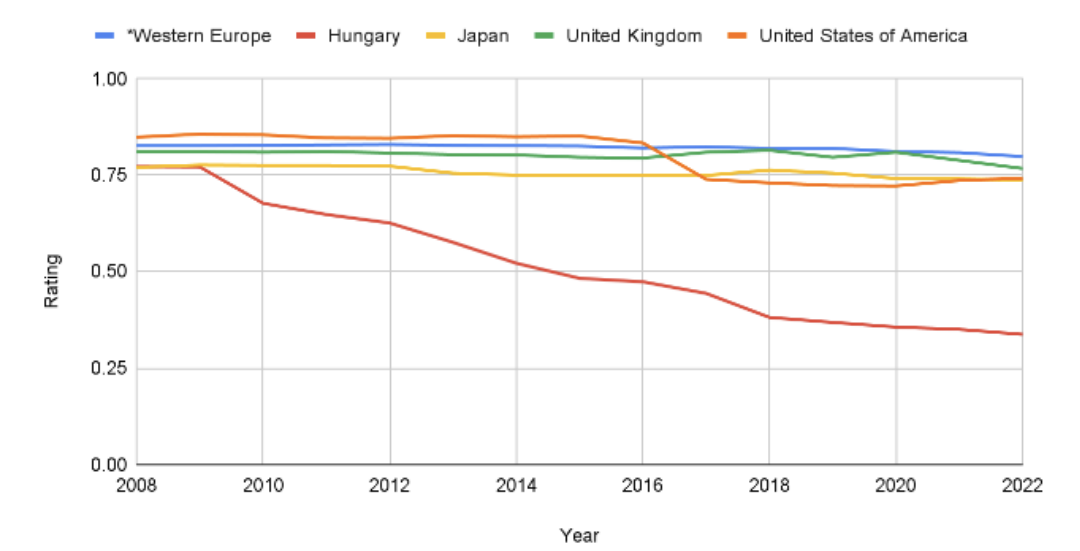

Democratic backsliding has become “a defining trend in global politics” over the past two decades, [14] spanning across high- [15], medium- [16] and low-income states. [17] As shown in the Liberal Democracy Index of Variety of Democracy Institute, while democratic backsliding was recorded in all regions, Europe has seen particularly alarming levels of democratic backsliding in the last decade (see Figure 2). [18]

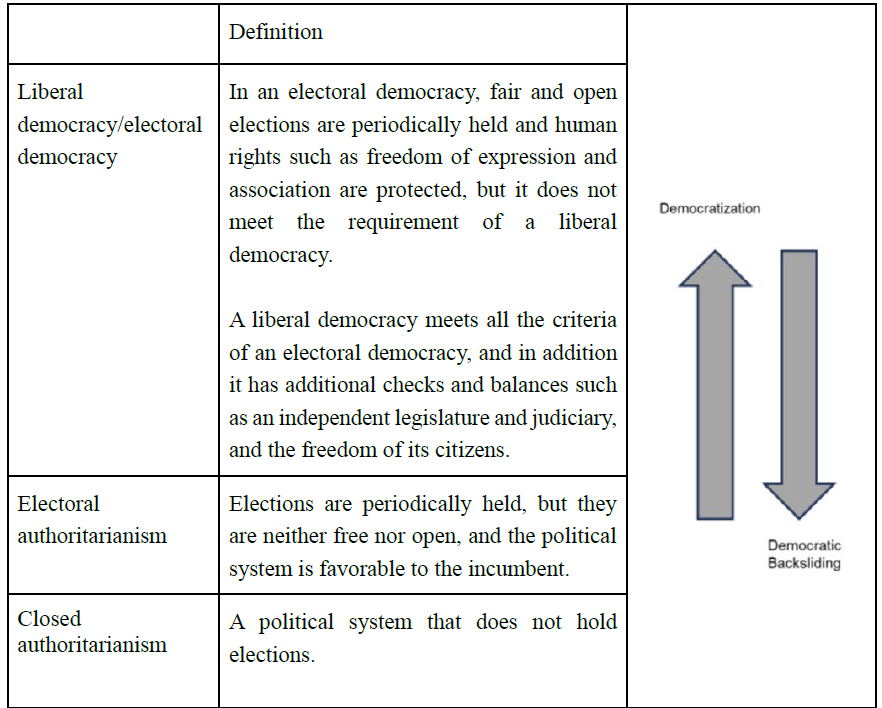

Democratic backsliding typically consists of “a retreat by an incumbent government from democratic values and practices”. [19] It does not necessarily happen overnight or through sheer force such as a coup, but is instead a result of a “discontinuous series of incremental actions” [20] that leads to an unintentional but steady erosion of democracy. [21] As shown in Table 2, democratic backsliding happens on a spectrum between closed authoritarian states that do not hold elections and liberal democracies that hold free and open elections with an independent legislature and judiciary. [22] While the partial erosion of democratic practices does not necessarily spell the end of democracy, if the incumbent violates so many of the existing democratic rules, it could, over time, lead to the state being no longer able to fully function as a democracy.

Figure 2: Democratic Backsliding  (Source: Created by the authors using data from V-Dem[23])

(Source: Created by the authors using data from V-Dem[23])

Table 2: Political Institutions and Democratic Backsliding (Source: Created by the authors based on Lührmann & Lindberg (2019), Kasuya (2024) and Nord et al. (2024) [24])

(Source: Created by the authors based on Lührmann & Lindberg (2019), Kasuya (2024) and Nord et al. (2024) [24])

Out of the three case studies selected for this report, Hungary illustrates the clearest signs of democratic backsliding. Figure 3 shows that based on the Liberal Democracy Index, Hungary faced the sharpest decline following the start of the second Orbán government, when electoral reform was introduced and the political and financial independence of the media came under scrutiny, making it one of the top ten countries that has autocratized. [25] The election of Donald Trump has also led the United States to dip based on this measure, and the metrics have hardly recovered since.

While the decline is not as pronounced as in the case of Hungary, the idea that the United States may no longer be considered a consolidated democracy is alarming. [26] Little change is evident for Japan and the United Kingdom, showing the durability of both liberal democracies. However, the Brexit process seriously tested the resilience of the United Kingdom’s liberal democratic institutions. Complacency is thus a risk, and therein lies the need for Japan to learn lessons from each case study to better prepare itself for future threats.

Figure 3: Liberal Democracy Index between 2008 and 2022  (Source: Created by the authors based on data from Varieties of Democracy[27])

(Source: Created by the authors based on data from Varieties of Democracy[27])

Why Should We Care About Disinformation in an Era of Democratic Crisis?

As discussed, democratic backsliding has occurred measurably on a global scale, including in Europe. Out of the three case studies in this report, Hungary’s case stands out as the most severe case of backsliding, but it remains a risk in the United States and is a potential long-term risk in the United Kingdom and Japan. This risk of democratic backsliding is especially pronounced when considering the threat of disinformation, which will be discussed below.

In Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way’s “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism,” they argue that there are “four arenas” (elections, legislature, judiciary, and the media) that become key battlegrounds for states that exist somewhere between democracy and autocracy. [28] The healthy functioning of all four arenas is what makes or breaks democracies.

Disinformation targets these institutions specifically and has consequential impacts on elections. For example, if it is perceived that the public makes a decision based on mis- or disinformation spread by domestic and/or foreign actors, it could lead to mistrust of election results. [29] A concrete example of this is offered in relation to Brexit, detailed in Chapter 3, concerning the infamous “£350m per week” claim which led to a debate over whether people were tricked into voting for Leave. [30] More broadly, this is arguably already happening, with a survey by Ipsos finding that disinformation and misinformation erodes public trust towards the media (40 percent of respondents) as well as the government (22 percent of respondents). [31] Disinformation not only targets elections, the legislature, the judiciary, and the media, it erodes its norms and presents a real threat to liberal democracies. Additionally, Larry Diamond argues that the mere functioning of these institutions alone is insufficient, and that for a country to be a true liberal democracy, it has to adopt liberal democratic norms. [32]

Benjamin Tallis takes this a step further by arguing that upholding and striving for the adoption of such democratic norms is “an interest in itself” for countries. [33] The concept of democratic norms comprises the “unwritten rules relating to the conduct of democracy, and include civility across party lines, acceptance of election outcomes, and tolerance for dissent.” [34] One of the dangers of disinformation is that such norms can be eroded. The violent January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol that resulted from former President Trump and his supporters refusing to accept the outcome of the 2020 election is one example of an erosion of such norms and its consequences.

In short, disinformation poses a substantive threat to democracies by attacking both their institutions and their norms. This is why this report focused on three democracies (Hungary, the United States, and the United Kingdom) in analyzing the threat of disinformation, as well as the potential policies to counter its spread. The final chapter provides an overview of the current situation in Japan and policy recommendations for Japan.

Three Risks of the Spread of Disinformation and Democratic Backsliding

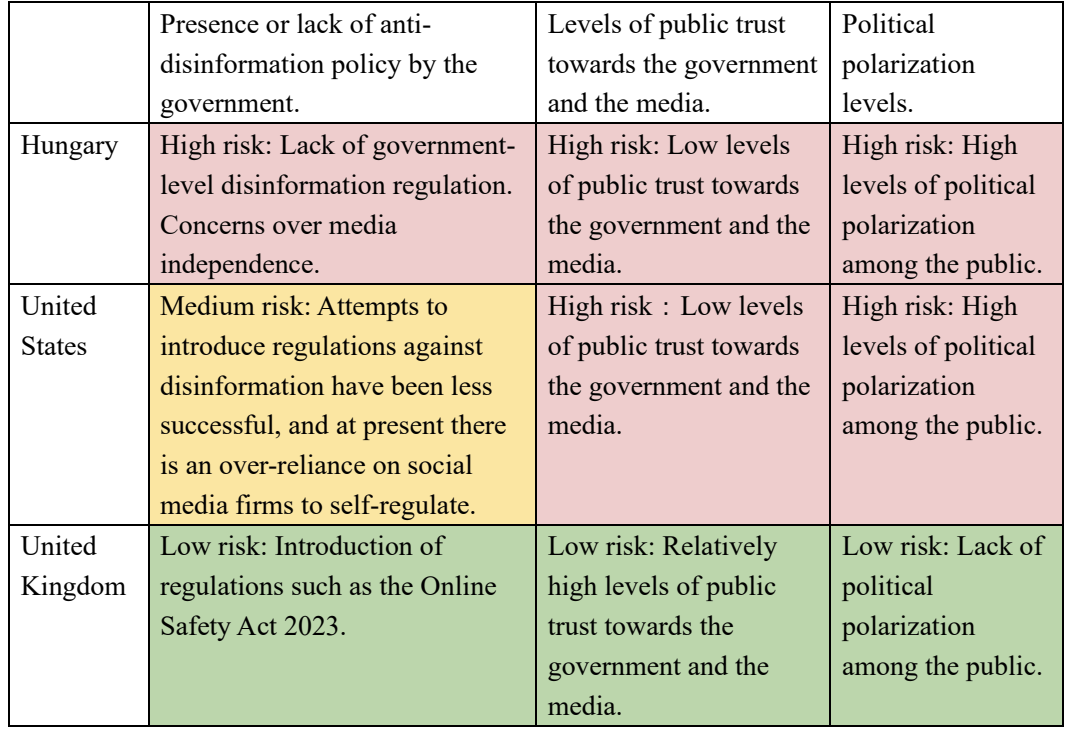

This report has explained what is meant by disinformation and why it poses a significant threat to democracies. This section sets out the framework for this report. We identify three key factors (‘enablers’) that contribute to the spread of disinformation and which erode the functioning of democratic institutions. These ‘enablers’ include the regulatory environment in which disinformation operates, distrust of institutions, and political polarization. Regulatory options against disinformation include content moderation of digital platforms such as those operated by large tech firms. We focus on the existence of checks for false information and a mechanism to delete or flag content if necessary. We follow a traffic light system by using red, yellow, and green to express the different levels of threat as shown in Table 3. Red shows a complete lack of regulations, yellow indicates partial and incomplete regulation, and green means a regulatory environment that is effective at combating disinformation.

Table 3: Risk Factors regarding the Spread of Disinformation and Democratic Backsliding (Source: Created by the authors)

(Source: Created by the authors)

Distrust refers to levels of public distrust towards democratic institutions such as the media and the government. Closely related to the concept of distrust is political polarization. A polarized public is less likely to be trusting, and the more distrustful people are, the higher the risk for further polarization. Disinformation therefore can also accelerate distrust [35] and polarization [36] in the same way the two can accelerate the spread of disinformation. While some level of healthy distrust of the government and media may be important in a democracy, [37] institutional trust is essential for the legislative process to function. In other words, a politically polarized and distrustful public will be skeptical of policies or new regulation put forth by its government. [38] As shown in the case of the United States, there is also the danger of lacking regulations when they are needed.

In the case of Hungary, according to the European Digital Media Observatory’s 2020 report, Hungary failed to introduce regulation to tackle disinformation. [39] The European Digital Media Observatory’s 2020 report is unequivocal in its criticism, stating that in Hungary, “the government itself is amplifying disinformation”. [40] While the European Union as an institution is at the forefront of introducing rigorous and holistic regulations against digital platforms, [41] there has been a lack of such policies from Hungary. [42] In Chapter 1 we argue that traditional Hungarian media outlets have published disinformation, and arguably politicians at the heart of government have been known to spread disinformation. In Hungary, public trust towards its media and government is in decline, [43] and the public are bitterly polarized. [44]

The United States suffers from political polarization as well as high levels of public distrust towards the government and the media, [45] which can further exacerbate polarization. [46] This presents a potential obstacle in passing legislation against disinformation as the public will be skeptical of government action. The government does not directly control traditional media outlets, but the public remains skeptical of mainstream news. Additionally, most of the global technology primes and social media platforms are based in the United States, but these firms remain insufficiently regulated, arguably allowing disinformation to continue spreading at an alarming rate. Legislation on this industry will also be difficult to achieve in the near term as long as the issues of institutional distrust and polarization among its public continue.

The United Kingdom differs from the other two case studies in that it enjoys a relatively high level of public trust towards its publicly funded media [47] and government [48] and it does not suffer from the level of political polarization seen in the United States. [49] It is true that the divide between Remain and Leave at one point became the defining identity in the aftermath of Brexit, [50] but Brexit is no longer a major concern for the public [51] and thus its ability to polarize the public has considerably declined. The United Kingdom, much like the United States, is in the process of introducing regulations against disinformation, and without the problems of polarization and public distrust, it is likely to enjoy a much less bumpy journey, which enables it to have a stronger regulatory environment that has the potential of tackling disinformation.

The situation in Japan is arguably closest to that of the United Kingdom in that its public is less polarized [52] and shows relatively higher levels of trust towards its media. [53] However, in contrast to the United Kingdom, while there are ongoing debates over disinformation policy in committee meetings, there is still a strong aversion to bringing in tougher regulations against disinformation in Japan. The main concern is over greater regulatory control which may result in a clash with freedom of speech, a key right that is protected under the Japanese Constitution. [54]

Report Structure

This report provides three case studies (Hungary, the United States, and the United Kingdom), followed by an overview of the current state of disinformation in Japan with a conclusion that presents five policy recommendations for Japan based on the findings from the three case studies. The report begins with Hungary, a country facing democratic backsliding we present how step-by-step media control was strengthened. We argue that disinformation from Russia and conspiracy theories as well as disinformation from Hungary itself is being spread by the media under the control of the government and government officials, which has led to greater public distrust and polarization in Hungary.

The second chapter analyzes the United States, tracing its history in relation to disinformation. The high level of public distrust towards the government is one of the key vulnerabilities in the current political climate. The polarized nature of political discourse in the United States further imperils its democracy. However, unlike the case of Hungary, the United States still has resources and a top-down willingness to manage disinformation. A multi-pronged approach by trusted actors in the public and private sectors is necessary to prevent disinformation from doing further damage to the country’s domestic political environment.

The third chapter on the United Kingdom is an example of a liberal democracy coming out of a crisis created by Brexit. The threat of disinformation looms large, especially the type of disinformation that weaponizes what this report terms the “engagement trap”. However, it has also managed to bring itself off of the precipice of the Brexit crisis, and is working to take a leading role in the global fight against disinformation. The chapter argues that one must fight fire with fire, and some of the more successful anti-disinformation tactics are those that can in fact use the “engagement trap” to their advantage.

The final chapter turns to Japan, a country that to this point has received relatively little academic attention in this field. The chapter provides a brief summary of the current state of disinformation in Japan, drawing comparisons with that of the previous three case studies. The chapter differentiates between disinformation during ‘peacetime’ and disinformation during moments of ‘crisis’. Such examples of the former include false claims during the Okinawa mayoral election (2018) while examples of the latter coincide with natural disasters. This distinction is important as the implications of disinformation can change dramatically depending on whether the readership is in ‘crisis’ mode or not. The timing may also affect how much a government is able to prevent disinformation from spreading on top of the original crisis at hand. While Japan may not face a critical juncture in its democratic identity like some of the other case studies, its recent history in experiencing disinformation during both peacetime and times of crisis makes it unique. While little academic attention has been paid to the issue thus far, Japan has not been standing idly by as the disinformation threat has increased. Steps have been taken to tackle the issue through the government as well as public-private partnerships, which is one of the key strengths of Japan. The chapter concludes by presenting five policy recommendations for Japan.

Footnote

- [1] European Parliament, “MEPs: Hungary can no longer be considered a full democracy,” European Parliament, September 15, 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220909IPR40137/meps-hungary-can-no-longer-be-considered-a-full-democracy.

- [2] See Thomas Rid, Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), for a detailed historical analysis.

- [3] Don Fallis, “What Is Disinformation?” Library Trends 63, no.3 (2015): 401-426, 406, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/579342.

- [4] Sille Obelitz Søe, “A unified account of information, misinformation, and disinformation,” Synthese 198 (2021): 5949-5949, 5931, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02444-x.

- [5] “Foreign Influence Operations and Disinformation,” Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), 2023, https://www.cisa.gov/topics/election-security/foreign-influence-operations-and-disinformation.

- [6] Disaggregated data from search queries on Google. Google News Initiative, “Basics of Google Trends,” Google News Initiative, February 20, 2024, https://newsinitiative.withgoogle.com/resources/trainings/google-trends/basics-of-google-trends/.

- [7] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, ed. Bernard Lott (London: Longman, 1968), 2.2.268.

- [8] Soroush Vosoughi et al., “The spread of true and false news online,” Science 359, no.6380 (March 2018): 1146-1151, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559.

- [9] Ibid.

- [10] Ullrich K. H. Ecker et al., “The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction,” Nature Reviews Psychology 1 (2022): 13-29, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y.

- [11] Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews, The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model: Why It Might Work and Options to Counter It (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2016), https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html.

- [12] Ibid.

- [13] Rid, Active Measures.

- [14] “Understanding and Responding to Global Democratic Backsliding,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 20, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/10/20/understanding-and-responding-to-global-democratic-backsliding-pub-88173.

- [15] Gi-Wook Shin, “South Korea’s Democratic Decay,” Journal of Democracy 31, no.3 (July 2020): 100-14, https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/south-koreas-democratic-decay/.

- [16] Robert R. Kaufman, and Stephan Haggard, “Democratic Decline in the United States: What Can We Learn from Middle-Income Backsliding?” Perspectives on Politics 17, no.2 (2019): 417–32, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718003377.

- [17] Evie Papada et al., Defiance in the Face of Autocratization: Democracy Report 2023 (Göteborg: Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2023), https://www.v-dem.net/documents/29/V-dem_democracyreport2023_lowres.pdf.

- [18] “Liberal Democracy Index,” Varieties of Democracy, last modified 2023, https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/VariableGraph/.

- [19] Richard Bellamy and Sandra Kröger, “Countering Democratic Backsliding by EU Member States: Constitutional Pluralism and ‘Value’ Differentiated Integration,” Swiss Political Science Review 27, no.3 (2021): 619–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12448.

- [20] David Waldner and Ellen Lust, “Unwelcoming Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding,” Annual Review of Political Science 21, no.1 (May 2018): 93-113, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628.

- [21] Nancy Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” Journal of Democracy 27, no.1 (January 2016): 5-19, https://journalofdemocracy.org/articles/on-democratic-backsliding/; Erika Frantz,Authoritarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- [22] Ibid, 61.

- [23] “Liberal Democracy Index.”

- [24] Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg, “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New about It?” Democratization 26, no.7 (2019): 1095–1113, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029; Marina Nord et. al., Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot (Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute, 2024), https://v-dem.net/documents/43/v-dem_dr2024_lowres.pdf; Yuko Kasuya, “Dai san shou: Minshushugi [Chapter Three: Democracy],” in Sekai no kiro wo yomitoku kisogainen: Hikaku seiji to Kokusai seiji heno sasoi [Basic Concepts to Understand the World at a Crossroad: Invitation to Comparative Politics and International Politics], eds. Kazuya Nakamizo and Sato Ryou (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2024).

- [25] There is the rather narrow definition of democratic backsliding which only refers to democracies that face backsliding, but in this report, we use the broader definition which includes democratic backsliding in authoritarian regimes. For a more detailed debate on the topic, please refer to the work by Kasuya (2024).

- [26] Vanessa A. Boese et al., Autocratization Changing Nature? Democracy Report 2022 (Göteborg: Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2022), https://v-dem.net/media/publications/dr_2022.pdf.

- [27] Andreas Schedler and Alexander Bor, The End of Democratic Consolidation in the US (Vienna: Central European University, Democracy Institute, 2024), https://democracyinstitute.ceu.edu/sites/default/files/article/attachment/2024-02/Schedler%20and%20Bor%20The%20End%20of%20Democratic%20Consolidation%20in%20the%20US%20CEU%20DI%20WP%202024_22_final.pdf.

- [28] “Liberal Democracy Index,” Varieties of Democracy. For further details on the measurements of the Liberal Democracy Index, please refer to the Varieties of Democracy’s “Structure of Aggregation.” Varieties of Democracy, Structure of V-Dem Indices, Components, and Indicators (Göteborg: Varieties of Democracy Institute, March 2023), https://v-dem.net/documents/28/structureofaggregation_v13.pdf.

- [29] Steven Levitsky and Lucan A Way, “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism,” Journal of Democracy 13, no.2 (2002): 51–65, https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/elections-without-democracy-the-rise-of-competitive-authoritarianism/.

- [30] Kousuke Saito, “Can we trust the polls? How emerging technologies affect democracy,” Geoeconomic briefing, April 16, 2024, https://apinitiative.org/en/2024/04/16/57247/.

- [31] Electoral Reform Society, It’s Good to Talk: Doing Referendums Differently (London: Electoral Reform Society, 2016), https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/latest-news-and-research/publications/its-good-to-talk/.

- [32] Ipsos Public Affairs, Internet Security and Trust (Toronto: Ipsos Public Affairs, 2019), https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2019-06/cigi-ipsos-2019-global-survey-on-internet-security-and-trust-pr.pdf.

- [33] Larry Diamond, Ill Winds: Saving Democracy from Russian Rage, Chinese Ambition, and American Complacency (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2019).

- [34] Benjamin Tallis, To Ukraine With Love: Essays on Russia’s War and Europe’s Future (Self-published, 2022).

- [35] Daniel E. Bergan, “Introduction: Democratic Norms, Group Perceptions, and the 2020 Election,” Journal of Political Marketing 20, no.3-4 (2021): 251-254, 251, https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2021.1939565.

- [36] Ruth Mayo, “Trust or distrust? Neither! The right mindset for confronting disinformation,” Current Opinion in Psychology 56 (2024): 101779-, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101779.

- [37] Pramukh Nanjundaswamy Vasist, Debashis Chatterjee, and Satish Krishnan, “The Polarizing Impact of Political Disinformation and Hate Speech: A Cross-Country Configural Narrative,” Information Systems Frontiers 26, no.2 (2023): 663–88, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-023-10390-w.

- [38] Onora O’Neil, “Linking Trust to Trustworthiness,” International Journal of Philosophical Studies 26, no.2 (2018): 293–300, https://doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2018.1454637.

- [39] Chris Dann, “Does public trust in government matter for effective policy-making?,” Economics Observatory, July 26, 2022, https://www.economicsobservatory.com/does-public-trust-in-government-matter-for-effective-policy-making.

- [40] European Digital Media Observatory, Policies to tackle disinformation in EU member states – part 2 (Florence: Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, European University Institute, 2022), https://edmo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Policies-to-tackle-disinformation-in-EU-member-states-%E2%80%93-Part-II.pdf; Judit Bayer et al.,

Disinformation and Propaganda: Impact on the Functioning of the Rule of Law and Democratic Processes in the EU and its Member States (Brussels: European Parliament, April 2021), 46, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/653633/EXPO_STU(2021)653633_EN.pdf. - [41] European Digital Media Observatory, Policies to tackle disinformation in EU member states; Konrad Bleyer-Simon, The Disinformation Landscape in Hungary (Brussels: EU DisinfoLab, 2023), https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/disinformation-landscape-in-hungary/.

- [42] For further information on regulation against disinformation from the EU towards social media providers, please refer to Takahisa Kawaguchi, “How democratic states are regulating digital platforms,” Geoeconomic Briefing, April 10, 2024, https://apinitiative.org/en/2024/04/10/57049/.

- [43] European Digital Media Observatory, Policies to tackle disinformation in EU member states – part 1 (Florence: Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, European University Institute, 2021), https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/74325/Policies-to-tackle-disinformation-in-EU-member-states-during-elections-Report.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- [44] Judit Szakács and Eva Bognar, “Hungary – Digital News Report 2023,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/hungary.

- [45] Federico Vegetti, “The Political Nature of Ideological Polarization: The Case of Hungary,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no.1 (2019): 78-96, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218813895.

- [46] Jeffrey M. Jones, “Americans Trust Local Government Most, Congress Least,” Gallup, October 13, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/512651/americans-trust-local-government-congress-east.aspx#:~:text=Trust%20in%20U.S.%20Government%20Institutions%20and%20Actors&text=Americans%20are%20most%20likely%20to,%2C%20with%2032%25%20trusting%20it.

- [47] Shanto Iyengar, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J Westwood, “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States,” Annual Review of Political Science 22, no.1 (2019): 129–46, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034.

- [48] Richard Fletcher, Alessio Cornia, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Measuring the reach of “fake news” and online disinformation in Europe (Oxford: Reuters Institute, 2018), 59, 81, 109 & 135, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-02/Measuring%20the%20reach%20of%20fake%20news%20and%20online%20distribution%20in%20Europe%20CORRECT%20FLAG.pdf.

- [49] Christian Haerpfer et al., eds., World Values Survey: Round Seven – Country-Pooled Datafile Version 5.0. (Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat, 2022), https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.20.

- [50] James Wright, “Polarisation and partisanship: 10 key takeaways from our World Values Survey conference,” The UK in the World Values Survey, April 24, 2024, https://www.uk-values.org/news-comment/polarisation-and-partisanship-10-key-takeaways-from-our-world-values-survey-conference.

- [51] UK in a Changing Europe, “New report reveals Brexit identities stronger than party identities,” UK in a Changing Europe, January 22, 2019, https://ukandeu.ac.uk/new-report-reveals-brexit-identities-stronger-than-party-identities/.

- [52] “The most important issues facing the country,” YouGov, accessed June 19, 2024, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/society/trackers/the-most-important-issues-facing-the-country.

- [53] “Political Polarization Index,” Varieties of Democracy Institute, last accessed October 29, 2024, https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/VariableGraph/.

- [54] Smart News Media, First Smart News Media Values National Survey: Symposium material for the media (Tokyo: Smart News Media Research Institute, November 24, 2023),

https://smartnews-smri.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/231124_SMPP.pdf.

(Photo Credit: Shutterstock)

About the Authors

Yusuke Ishikawa(Research Fellow)

After receiving his BA in Political Science from Meiji University, he completed an MA inCorruption and Governance (with Distinction) from the University of Sussex, and an MA in Political Science from Central European University. He also works remotely as an external contributor for the Anti-Corruption Helpdesk at Transparency International Secretariat (TIS) in Berlin.

Marina Fujita Dickson(Research Associate)

After receiving her BA in Politics and History from Bates College, she completed an MA in Strategic Studies and International Economics with a minor in Korea Studies from the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University. At SAIS, she worked as a Research Assistant under Dr Thomas Rid focusing on disinformation and information security. Prior to her Masters, she worked at the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies as a Policy Research Fellow with Dr. Kent Calder and as a senior strategy consultant at The Beacon Group (now Accenture).

Dr Sara Kaizuka FHEA(Part-time Lecturer at Musashino University / Part-time Assistant Lecturer at Kanagawa University / Intern at the IOG)

After receiving her BA in International Liberal Studies from Waseda University, she completed an MA in Politics at the University of Leeds from which she also received her PhD in Politics. At the University of Leeds, she taught International Politics, Comparative Politics, and British Politics. At present, she teaches at Musashino University and works as a part-time lecturer assistant at Kanagawa University.

A dangerous confluence: The intertwined crises of disinformation and democracies: Contents

Introduction

The Definition and Purpose of Disinformation / Democratic Backsliding / Why Should We Care About Disinformation in an Era of Democratic Crisis? / Three Risks of the Spread of Disinformation and Democratic Backsliding / Report Structure

Chapter 1 Hungary: Media Control and Disinformation

Democratic Backsliding: Increased Control over Information Sources Through Media Acquisitions / Disinformation Through the Media and Its Impact: The Refugee Crisis / The Russia-Ukraine War: The Import and Export of Disinformation / The Negative Impact of Disinformation

Chapter 2 Disinformation in the United States: When Distrust Trumps Facts

The Early Years of American Disinformation: / The American Context: Distrust, Past and Present / The Challenge for Newsrooms / Managing Disinformation Through the Spreader & Consumer

Chapter 3 The Engagement Trap and Disinformation in the United Kingdom

Dragging Their Feet: Initial Slow Response to the Disinformation Threat / The Engagement Trap / A New Level of Threat to Democracy / Combatting Disinformation

Conclusion: Disinformation in Japan and How to Deal with It

Disinformation During Elections and Natural Disasters in Japan / Disinformation Policies During Crises: The 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election as Case Study / Disinformation During Crises: The Noto Peninsula Earthquake and Typhoon Jebi / Policy Recommendations

Disclaimer: Please note that the contents and opinions expressed in this report are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the International House of Japan or the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG), to which the authors belong. Unauthorized reproduction or reprinting of the article is prohibited.

Research Fellow,

Digital Communications Officer

Yusuke Ishikawa is Research Fellow and Digital Communications Officer at Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG). His research focuses on European comparative politics, democratic backsliding, and anti-corruption. He also serves as External Contributor for Transparency International’s Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, as Associate Research Fellow at the EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, and as Part-time Lecturer in European Affairs at the Department of Economics and Business Management, Saitama Gakuen University. Prior to his current roles, Research Associate at IOG and API, contributing to its translation project of Critical Review of the Abe Administration into English and Chinese. Previously, he has worked as Research Assistant for API's CPTPP program and interned with its Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Abe Administration projects. His other experience includes serving as a visiting research fellow at EUEOPEUM Institute, a full-time research intern at Transparency International Hungary, and as a part-time consultant with Transparency International Defence & Security in the UK. His publications include "NGOs, Advocacy, and Anti-Corruption" (In Routledge Handbook of Anti-Corruption Research and Practice, 2025) and A Dangerous Confluence: The Intertwined Crises of Disinformation and Democracies (Institute of Geoeconomics, 2024). He has been featured in national and international media outlets including Japan Times, NHK, TV Asahi, Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), Handelsblatt, Expresso, and E-International Relations (E-IR). He received his BA in Political Science from Meiji University, MA in Corruption and Governance (with Distinction) from the University of Sussex, and another MA in Political Science from Central European University. During his BA and MAs, he also acquired teacher’s licenses in social studies in secondary education and a TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Language) certificate. [Concurrent Positions] Associate Research Fellow, EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, Czechia External Contributor Consultant, Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, Transparency International Secretariat (TI-S), Germany Part-time Lecturer, Department of Economics and Business Management, Saitama Gakuen University, Japan

View Profile

Research Associate

Marina Dickson earned her Master of Arts in Strategic Studies and International Economics with a minor in Korea Studies from the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University. At SAIS, she worked as a Research Assistant under Dr. Thomas Rid focusing on disinformation and information security. Prior to her Masters, she worked at the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies as a Policy Research Fellow under Dr. Kent Calder. She also has experience working as a senior consultant at The Beacon Group, supporting Fortune 500 companies in defense, technology, and healthcare industries navigate new market opportunities. She holds a Bachelor of Arts from Bates College in Politics and History.

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08