Chapter 2 Disinformation in the United States: When Distrust Trumps Facts

The challenge posed by disinformation in the United States can be described as two interlocked problems. On the one hand, disinformation is rampant and a growing number of Americans believe in claims rooted in disinformation or conspiracy theories. One alarming statistic shows that as of 2023, a third of Americans believe that former President Donald Trump “rightfully won” the 2020 election, another third believe in “Great Replacement Theory” (a belief that elites are conspiring to replace white “native” Americans with illegal immigrants), and one in four Americans believe in QAnon. [1] At the same time, public trust in institutions is at a historic low, and many Americans are skeptical of the federal government’s ability to function and operate in the public’s best interest.

This paper will explore how these domestic political factors of public sentiment influence the disinformation challenge in the U.S. and its approach to combating it. A skeptical public is the ideal target for disinformation campaigns: nefarious actors both domestic and foreign can exploit their targets to further undermine institutional trust and exploit societal cleavages. This can lead to further political polarization, perpetuating a cycle of distrust, and leading to decay in democratic norms. The following discussion will delineate the American context that created this political and social environment, and argue why a holistic approach involving government, technology companies, and traditional media is necessary to manage this challenge.

The Early Years of American Disinformation

The 2024 U.S. presidential election will be a unique election for the history books. The race began with two incumbents facing each other off for the second time. Less than a month before the democratic convention, President Biden dropped out of the race to pass the baton to his sitting vice president, Kamala Harris. A key reason of his decision to drop out was the growing criticism from the public that he was “too old” to hold office again – a criticism former President Trump has also faced, though less severely. The announcement came as a shock to many voters, but a shock maybe rivaled only by assassination attempt on Trump a week prior.

Despite the whirlwind of events that have made up this campaign season, many aspects of this election are not new. Modern day election cycles across the globe all face the challenge of disinformation and the United States is no exception, though the issue has existed for centuries.

In the U.S. Presidential Election of 1796, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams went head to head for the presidency after George Washington announced he would not seek a third term. The domestic political environment at the time was perfect for disseminating disinformation. In the years leading up to the election, newspapers had become politicized, not unlike the media landscape of today. The two candidates instigated smear campaigns against each other, with Adams supporters spreading rumors that Jefferson had “intrinsic character defects” and Jefferson supporters attacking Adams for conspiring to be “King of the United States” by sending one of his children to marry into the British royal family. [2] Neither story was based on any objective truth, but the narratives ran nonetheless.

The United States again faced the challenge of information warfare throughout the following centuries, but during the Cold War the source was a foreign adversary. The Soviet Union devised a number of disinformation campaigns, or “active measures”, some of which were acutely damaging to the American public’s trust in their own government. One particular campaign, known as “Operation Denver”, purported that the United States had developed the HIV/AIDS virus as a biological weapon at a base in Maryland. [3] In 1985, the KGB, seeking to create a favorable opinion of the USSR abroad, tasked East Germany’s secret police, the Stasi, and two retired biologists to publish a study to make this claim believable based on “scientific fact.” Pamphlets describing this study were distributed at a non-aligned movement summit in Zimbabwe a year later, where local journalists from participant countries picked up the story. [4] Within a few years, documentaries were being made in English interviewing the biologists on their claims, further spreading the story to the anglophone world. With AIDS disproportionately impacting the LGBT community in the United States, and the growing frustration with the stigma and callous government response to the epidemic, many in the United States were ready to believe the government was indeed responsible for creating the virus. Black Americans were also disproportionately impacted, prompting some of them to believe similar conspiracy theories given their existing distrust of the public health system. [5] The Soviets had thus picked a perfect time to exploit the existing distrust in the United States to spread a theory blaming the U.S. government for the virus that many Americans were ready to believe. [6] The University of Chicago found that even decades later, more than one in ten Americans still believed that the U.S. government created HIV and deliberately infected minority groups with the virus. [7]

While these Soviet-backed active measures were a significant part of the conspiracy and information battlegrounds of the Cold War decades ago, the distrust Americans feel towards their government institutions has not dissipated. Rather, distrust in public institutions persists, undermining the ability to fight disinformation today.

The American Context: Distrust, Past and Present

For the American public, the Cold War years was a period of growing skepticism of the government. McCarthyism had suppressed the free speech of leftists and others, which was followed by misinformation throughout the following decade about how the United States was “winning” the war in Vietnam, followed by the political scandals of the Nixon administration. [8]

That skepticism has never really waned, and Americans have become even more distrustful of their government over the years, according to a Pew Research Center’s aggregation of polling data from 1953. When asked in 2023, less than 20 per cent of Americans trusted the government to “do the right thing most of the time.” [9] This number has been steady in the last ten years, but it is still a striking statistic in comparison to other times when American politics was turbulent. For instance, during the years of the Watergate scandal, trust in the government to ‘do the right thing’ was at 36 per cent. Meanwhile, 59 per cent of Americans had “not very much or no” confidence in the executive branch (the President) in 2023, up from 49 per cent in 2022. [10] The last time a majority of Americans trusted the government overall was 2001. [11]

The lack of confidence the public has in its elected government not only affects public messaging and its ability to reach most Americans but also creates an environment that bad actors, foreign or domestic, can exploit. In the introduction, the authors of this report illustrated how the coexistence of an unregulated media environment, a distrust in government, and the persistence of political polarization can exacerbate the disinformation challenge, making it more complicated to tackle. In the case of the United States, the government does not directly control media outlets themselves in the same way that Hungary does, but traditional media outlets are distrusted by viewers nonetheless. This can create an environment in which other, less credible sources and unregulated platforms can compete for views and false information can spread more easily. With a lack of credible, trusted information, and disinformation spreading in its place, Americans’ trust in their government is further undermined, and any government effort to counteract the disinformation is deemed untrustworthy itself. The combination of these forces contributed to the dip in the liberal democracy index for the U.S. by 2016, when the American political landscape was ripe with disinformation.

Foreign interference was an acute challenge that affected the 2016 presidential elections. That year, over 30,000 X (formerly Twitter) accounts that were posting about the presidential election were found to be run by Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA), an organization that engaged in influence operations on behalf of the Russian government between 2013-2018. [12] Not unlike their strategy during the Cold War, the Kremlin wanted to use the media to create confusion, chaos, and distrust within its adversary’s public, while obfuscating the origin of the claim’s source. Instead of using foreign journalists and third countries to spread propaganda through the printed press, Russia relied on social media for the same effect. [13] This served as a wake-up call for the U.S. government to manage foreign meddling in its elections going forward. While foreign actors continued in their attempts to influence American newsrooms, four years later, much of the disinformation was coming from within.

In 2020, President Trump lost his reelection. He had predicted this, not because he believed he would genuinely lack the votes, but because he believed incorrectly that there was widespread voter fraud in the country designed to disadvantage him. By claiming that the United States had a voter fraud problem that was unfavorable to him and his party since he first won in 2016, Trump was able to preemptively normalize the narrative among his supporters that if he lost an election, it would not be because of a lack of votes, but because of voter fraud. [14] By the time he lost in 2020, his supporters already believed that the election was rigged, and were ready to spread the narrative of election fraud themselves. The same narrative pattern can be seen in the 2024 election. This phenomenon of uncoordinated actors spreading false information, coined “participatory disinformation”, differs from intentional, often state-sponsored bad actors, and describes unwitting participants that spread false claims that are favorable to a political figure like Trump. [15]

To add to the confusion and chaos, organizations backing Trump, such as Turning Point USA, had been engaging in coordinated messaging on social media in 2020 to help his campaign by spreading conspiracy theories about his opponent. [16] Through thousands of fake accounts, Turning Point USA would present themselves as liberal voters, targeting other democrats to vote for a third-party candidate that could be “more progressive” than Biden thereby helping Trump win if this support was withheld. The organization’s accounts were not always directly calling on voters to vote for Trump; rather, they were working to sow enough confusion in the liberal voter base to not vote for Biden. Individuals and organizations can thus benefit from the public’s distrust, either wittingly or unwittingly, to spread disinformation in favor of their preferred candidate.

The Challenge for Newsrooms

In addition to distrust of the government, the United States is also experiencing public distrust of news and media. A Gallup poll from 2022 found that half of Americans say they do not trust national news, especially those who consume news online. 50 per cent of respondents also stated they believed that the news organizations “intend to mislead, misinform, and persuade” the public. [17]

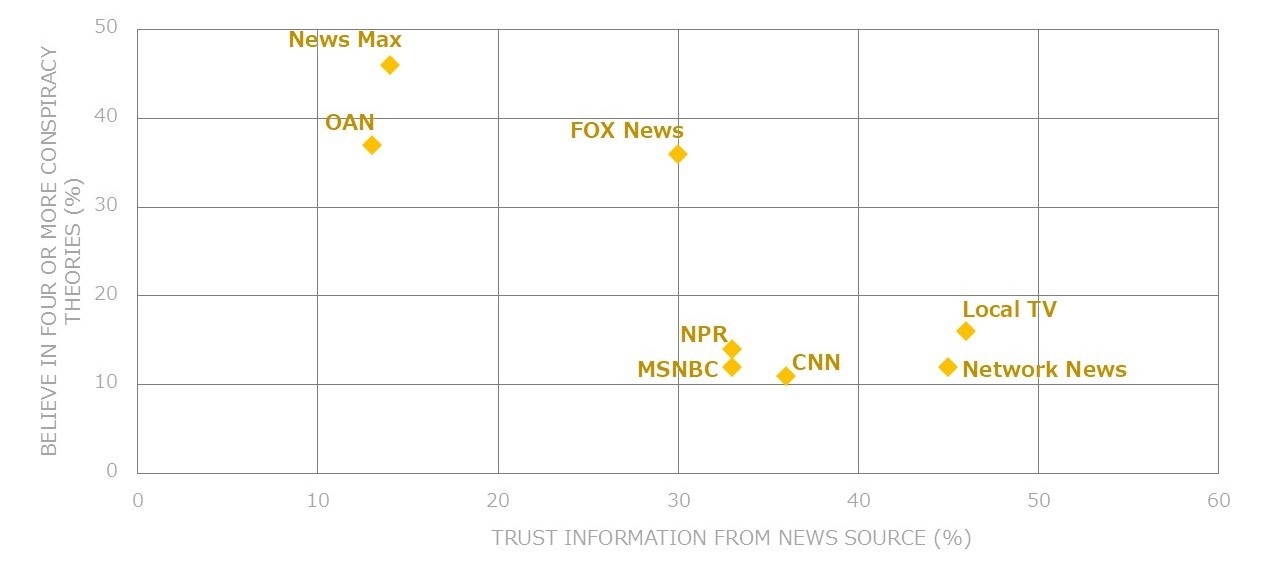

It is clear from both the outlets and viewers that disinformation is overwhelmingly more of a right-wing issue than a left-wing issue. [18] When divided by party, 86 per cent of Republicans say they do not trust the news, while only 29 per cent of Democrats feel the same. However, when Republicans and Democrats are asked whether they trust their preferred news outlets, their levels of trust are the same. In other words, conservatives who watch Fox News trust the outlet as much as liberals who watch NPR or MSNBC. [19] When those same respondents are asked whether they believe in conspiracy theories, more than twice as many conservatives state they do believe in conspiracy theories compared to their liberal counterparts. The number of prominent conservative news anchors and commentators such as Tucker Carlson (formerly Fox News) and Steve Bannon (formerly Breitbart) who create and spread misinformation, but are immensely popular, underscores this point.

Trump himself repeated false or misleading assertions to his Republican base throughout his presidency, including claims about the economy, COVID-19 treatments, and his meetings with foreign officials. The Washington Post tallied all of these claims during his time in office and found that Trump averaged 20.9 lies or partial lies per day. [20] It is no surprise that some of these played into the spread and belief of disinformation among his supporters and conservative outlets that repeated these claims.

Figure 1: Trust in News vs Acceptance of Conspiracy Theories (Source: Created by author using data from YouGov [21])

(Source: Created by author using data from YouGov [21])

This imbalance requires journalists to be judicious in their reporting on disinformation, particularly regarding the origins of a false claim or conspiracy theory. What may appear to be foreign disinformation spreading in the United States may actually have originated domestically. For instance, Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican lawmaker, argued against sending additional aid to Ukraine in the fall of 2023, citing an article from a Russian outlet that claimed the Ukrainian President was making personal purchases with the aid money. It may have seemed like Greene was touting ‘Kremlin talking points’, but this claim in fact originated from Vice Presidential candidate and Senator, JD Vance, over a year earlier. The Russian outlet simply amplified what he had said. Baseless or misleading claims require sufficient scrutiny, but pinpointing the origin of the disinformation is just as important to not overstate the influence of foreign malign actors. Disinformation scholars argue that when foreign influence campaigns are exaggerated, especially by news outlets, it both aids the operative and “fosters a conspiratorial outlook” domestically which further erodes trust in public debate. [22]

Managing Disinformation Through the Spreader & Consumer

While the persistence of distrust in the government and the existence of disinformation is not new, the current media environment and increased digitalization of news and information have multiplied the effects of disinformation on public trust. Given the number of challenges that further exacerbate the challenge of disinformation, how can the United States better tackle the spread and effects of disinformation?

Education

One aspect in which the effect of disinformation can be curtailed is on the consumption side. Currently, Americans score relatively low in media literacy compared to their peers. [23] Finland is a valuable example of a country that has also been the target of disinformation but scores much more highly on media literacy. Like the United States, Finland has a history of being targeted by Russian disinformation campaigns, but unlike the United States it has the highest media literacy among OECD countries – media literacy is mandated in public schools and students are taught media literacy starting in pre-school, learning how to decipher fact from fiction early on. Finnish students discuss problems they may encounter in news and media across different subjects, from writing class to health class. [24] Finns also enjoy a high level of trust in their government (61 percent) and news (69 percent), and feel that their government is transparent, making the landscape difficult for bad actors to exploit. [25]

By comparison, only three out of the 50 U.S. states have K-12 media literacy education. [26] A greater emphasis on media literacy in public schools would help Americans better decipher their information intake, but would require increasing public education funding, as well as depoliticizing curricula across the country, both issues which the United States is already struggling to address. At the same time, some effort is being made more recently by providing grants to local libraries and other organizations to offer media literacy education.

Government

While legislation to curb disinformation is also necessary, the U.S. government finds itself in a difficult spot. According to political scientist Friedel Weinert’s “The Role of Trust in Political Systems”, trust in institutions is an essential condition for a democratic society to properly function and deliver the expected services to the public, whether it may be information or resources. [27] Because of the existing distrust in the United States, efforts to control disinformation by the government can be seen as controlling information for the public writ large. For instance, the Department of Homeland Security established a Digital Governance Board in April 2022 to “tackle disinformation” that threatens national security. [28] It was paused only three weeks later and quickly disbanded after critics argued that the board was partisan and could undermine First Amendment rights to free speech if its objective was to enforce an “official” version of the truth.

A more effective approach would be for the government to engage in public service campaigns that can relay specific methods or attributes of disinformation that the public should be aware of without focusing on specific claims. State and local governments, which tend to be more trusted than the federal government, could provide information on how to spot misinformation or other unsubstantiated claims that they may see in media, empowering voters regardless of their political preferences. Trust in institutions is an essential condition for a democratic society’s proper functioning to ensure that the public is getting the services that can relay specific methods or attributes of disinformation that the public should be aware of without focusing on specific claims. State and local governments, which tend to be more trusted than the federal government, could provide information on how to spot misinformation or other unsubstantiated claims that they may see in media, empowering voters regardless of their political preferences.

Specific to efforts during election season, the Federal Election Commission (FEC) has been working to institute new rules on AI to create guardrails for its use in political advertisements. Currently, only five states have laws regulating deep fakes in political advertising, meaning federal laws could radically change what ads candidates can use. The FEC indicated that they will announce new guidelines in the summer of 2024, but ultimately announced in September it would enact no new legislation this year. [29]

Finally, the national government should establish deterrent mechanisms for candidate-adjacent organizations that attempt to sway elections through coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) online. [30] Nonprofits in particular should be strictly scrutinized if they are using organizational resources to support a specific candidate. 501(c) status should be revised so that it limits not only direct campaigning but certain forms of coordinated indirect campaigning such as the kind Turning Point USA engaged in.

Press and Media

As disseminators of news and information, traditional press and media organizations shoulder a great responsibility to fight disinformation. Fortunately, some of the major media organizations have already developed fact-checking mechanisms and created resources to investigate AI-generated deep fakes.

CBS News launched “CBS News Confirmed” to investigate misinformation and inauthentic images and videos. FOX News launched “Verify” earlier this year, an open-sourced tool that allows consumers to verify if the images or articles they find purporting to be from FOX sources are authentic or not. Hearst Communications, a conglomerate that owns a number of local TV stations, newspapers, and magazines, partnered with FactCheck.org to produce segments that combat misinformation for local stations across the country. Local news media in the United States plays a particularly critical role in debunking misinformation and disinformation as it tends to be more trusted than national news; for instance, Americans are twice as likely to trust local news over national news regarding voting information. [31] Funding local news stations is thus imperative to delivering accurate and reliable information to the voting public.

Trusted organizations can also step in to debunk untrue claims, which is especially helpful in a crisis situation. For instance, a lot of misinformation had spread after Hurricane Katrina, so the American Red Cross hired a media specialist to provide factual and resourceful information on online forums and directly engage with forum users to put out any misinformation ‘fires’ before they further spread. [32] Additionally, U.S. newsrooms have made it commonplace to embed links of original source reporting in related articles, which can help readers know the initial source of a claim and aid in fact-checking efforts.

Timely and reliable fact-checking has become crucial in stopping the spread of disinformation, especially in relation to political campaigns. In this election season, AI-generated video and audio clips of political candidates have already spread. Before the New Hampshire primary in January, voters received thousands of robocalls impersonating Joe Biden urging them not to vote in the primary election and “save [their] vote for November.” An investigation by the voice detection company Pindrop Inc was able to identify the audio technology to be from an Eleven Labs voice generator, and reporters were able to trace the call back to a company based in Texas just days later. [33] The FCC subsequently slapped multi-million dollar penalties on those responsible, signaling the gravity of the crime. [34] In addition to AI, malign actors have also resorted to “cheap fakes”, using less-sophisticated software to alter the voice or images of candidates. Harris has been the target of such cheap fakes since she has become the top name on the Democratic Party’s ticket.

At the same time, as much as it is dangerous for the public to believe that an inauthentic claim or video clip is real, the opposite is equally dangerous. If viewers believe that the information they see can never be trusted because of how believable AI-made content is, they will have fewer sources to go to for accurate and reliable information. This can lead to a kind of ‘information nihilism’, where people are unable to differentiate between what is true and false, and give up entirely on believing any news. This not only exacerbates distrust in media institutions but can also lead to a disengaged public, creating more distance between a country’s institutions and people. Journalists and news companies thus play a critical role in keeping up with new technologies that generate inauthentic content, and debunking false information quickly and reliably.

Tech Giants

The private sector, namely technology companies, have arguably the most flexibility in instituting policies to counter or remove disinformation. With growing scrutiny from American lawmakers, search engine and social media companies are adopting new ways to detect and manage disinformation as well as AI-generated content.

TikTok, for instance, requires users to label content made with AI as fake, while YouTube bans the use of AI in political advertisements on its platform. Starting this July, Google started generating disclosures whenever advertisers label election ads as containing “synthetic or digitally altered content” as is required by political advertisers. [35] Although these rules may show some progress, such policies are difficult to enforce, and they are not uniform across companies. X has the least strict policy among its counterparts regarding the use of AI, stating that most content is allowed as long as it is not “significantly and deceptively altered.” [36] Meta, on the other hand, established a new policy for the 2024 election season, in which political ads are banned 10 days before an election and manipulated videos and images are subject to fact-checking, but even its own oversight board said the policy was insufficient. Concerns can also mount when technology companies cycle through mass layoffs, often targeting teams that manage inauthentic online content. In the last year alone, X laid off 80 per cent of its trust and safety engineers, as well as more than half of its content moderators, suggesting that managing disinformation on the platform is not a strong priority for them. Lawmakers must incentivize these companies through policy legislation to more stringently moderate content so disinformation does not spread on their platforms.

Legally, technology companies cannot be held liable for content that is posted by a third party according to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which effectively means that a social media platform cannot be treated as the publisher of its online content. Given that this law was passed in 1996 before the modern-day tech giants existed, its provisions are outdated relative to the challenges currently faced. [37] Although other countries such as the United Kingdom have taken steps for companies to be held liable for its content through the Online Safety Act (2023), these laws should not target E2EE (end-to-end encryption) processes that would undermine individual privacy and civil liberties of users. Rather, given that magazines and newspapers in the United States can be sued if they intentionally provide false information, a similar law could be applied to companies such as Meta or X as well, given that more than half of Americans get their news on social media. [38]

Further regulation of web hosts or content delivery networks that technology companies rely on (e.g. Amazon’s App Store, Amazon’s Web Services, etc.) could further incentivize platforms to control the sharing and spread of misinformation more proactively. [39] AI companies whose technology can be used to create fake content should also face more stringent regulation to prevent the use of clips like the Biden New Hampshire robocall from spreading. While the signing of an accord at the Munich Security Conference in February by major technology companies to adopt “reasonable precautions” regarding AI is a good symbolic step, such commitments need to be binding to have more sway. [40]

Companies can also be more proactive in developing tools that counter disinformation. Anthropic recently introduced “Prompt Shield”, a tool that provides voters with unbiased election information that is more comprehensive than a Google search. Prompt Shield functions as an attached tool to Claude, Anthropic’s chatbot, and directs users to nonpartisan websites with voting information. [41] Because many of the existing chatbots including Claude, ChatGPT-4, and Gemini are ill-equipped at providing real time information that prompts them to “hallucinate”’ and make up information that is not true, the tool bypasses this issue by simply redirecting to an authoritative source. As actors in the production of disinformation, technology companies have an immense responsibility to not only prevent their tools from being exploited by nefarious actors, but should also feel incentivized to develop tools that support fact-checking and detect disinformation.

Given both the difficulties on both the consumption and dissemination sides of the disinformation challenge in the United States, a multi-pronged approach that involves both public and private sector stakeholders is necessary to tackle this issue. Disinformation cannot be eliminated, but it can be managed with the right policies in a healthy democracy. In a high-stakes election year, the U.S. approach to confronting this issue will not only be consequential for its own future, but in the global fight against disinformation in years to come.

Footnote

- [1] QAnon is a far right-wing, loosely organized network and community of believers who embrace a range of unsubstantiated beliefs, including the idea that the world is controlled by the “Deep State,” that emerged in 2017.

See “Threats to American Democracy Ahead of an Unprecedented Presidential Election,” PRRI, October 25, 2023. - [2] James W. Cortada, “How new is ‘fake news’?” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, March 23, 2017).

- [3] Mark Kramer, “Lessons From Operation ‘Denver,’ the KGB’s Massive AIDS Disinformation Campaign,” The MIT Press Reader, May 26, 2020, https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/operation-denver-kgb-aids-disinformation-campaign/.

- [4] Ibid.

- [5] From 1932 to 1972, the U.S. Public Health Service conducted the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which the government observed the long-term effects of syphilis on infected African-American sharecroppers and their offspring without providing them with effective medical treatment, even after penicillin had proven effective against the disease. Participants’ informed consent was also not collected. See: “The Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee Timeline,” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, December 05, 2022.

- [6] Calder Walton, “What’s Old Is New Again: Cold War Lessons for Countering Disinformation,” Texas National Security Review, 2022, http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/43940.

- [7] University of Chicago study from 2013, see J. Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood, “Medical Conspiracy Theories and Health Behaviors in the United States,” JAMA Internal Medicine 174, no.5 (2014): 817–818, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.190.

- [8] For a comprehensive explanation on the historical context of distrust amongst the U.S. electorate, see: Stephen Mihm, “Don’t Panic: Distrusting Government Is an American Tradition,” Bloomberg, September 12, 2024.

- [9] “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2023,” Pew Research Center, September 19, 2023.

- [10] Jeffrey M. Jones, “Americans Trust Local Government Most, Congress Least,” Gallup, October 13, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/512651/americans-trust-local-government-congress-least.aspx.

- [11] Matteo Serafino et al., “Suspended accounts align with the Internet Research Agency misinformation campaign to influence the 2016 US election,”

EPJ Data Science 13, no.29 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-024-00464-3. - [12] U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, S. Rep. – 116 Congress (2019-2020): Russian Active Measures Campaigns and Interference in the 2016 U.S. Election, Volume 2: Russia’s Use of Social Media with Additional Views (Washington D.C.: U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, October 09, 2019), https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report_Volume2.pdf.

- [13] Stephen Collinson, “Why Trump’s talk of a rigged vote is so dangerous,” CNN Politics, October 19, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/10/18/politics/donald-trump-rigged-election/index.html.

- [14] Kate Starbird, Renée DiResta, and Matt DeButts, “Influence and Improvisation: Participatory Disinformation during the 2020 US Election,”

Social Media + Society 9, no.2 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177943. - [15] Isaac Stanley-Becker, “Pro-Trump youth group enlists teens in secretive campaign likened to a ‘troll farm,’ prompting rebuke by Facebook and Twitter,”

Washington Post, September 16, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/turning-point-teens-disinformation-trump/2020/09/15/c84091ae-f20a-11ea-b796-2dd09962649c_story.html. - [16] “American Views 2022: Part 2, Trust Media and Democracy,” Gallup Media & The Knight Foundation, January 2023, https://knightfoundation.org/reports/american-views-2023-part-2/.

- [17] Recent research into the asymmetry between conservatives and liberals in the United States has found that a substantial segment of the online news ecosystem is consumed “exclusively by conservatives and that most misinformation exists within this ideological bubble.” Additionally, disinformation researchers found that the structure of the American media scene, which includes a “dense interconnected cluster of right-wing sources that is separate from the remaining mainstream, fosters political asymmetry in the use and consumption of disinformation.” See: Stephan Lewandowsky et al., “Liars know they are lying: differentiating disinformation from disagreement,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11, no.986 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03503-6; Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts, Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics (Oxford: Oxford Academic, October 18, 2018).

- [18] News consumers on both sides of the political spectrum may be distrustful of news media, but tend to make exceptions for outlets that align with their own political views.

Taylor Orth and Carl Bialik, “Trust in Media 2024: Which news sources Americans trust — and which they think lean left or right,” YouGov, May 30, 2024, https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/49552-trust-in-media-2024-which-news-outlets-americans-trust. - [19] Glenn Kessler, Salvador Rizzo, and Meg Kelly, “Trump’s false or misleading claims total 30,573 over 4 years,” Washington Post, January 24, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/24/trumps-false-or-misleading-claims-total-30573-over-four-years/.

- [20] Taylor Orth and Carl Bialik, “Trust in Media 2024, YouGov, May 30, 2024, https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/49552-trust-in-media-2024-which-news-outlets-americans-trust.

- [21] Olga Belogolova et al., “Don’t Hype the Disinformation Threat: Downplaying the Risk Helps Foreign Propagandists—but So Does Exaggerating It,” Foreign Affairs, May 03, 2024,

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/dont-hype-disinformation-threat. - [22] Marin Lessenski, Media Literacy Index 2021 (Sofia: Open Society Institute, 2021), https://osis.bg/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/MediaLiteracyIndex2021_ENG.pdf.

- [23] European Commission, National reports on media literacy measures under the Audiovisual Media Services Directive 2020-2022: National Report from Finland, European Commission (Brussels: European Commission, May 2023), https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/national-reports-media-literacy-measures-under-audiovisual-media-services-directive-2020-2022.

- [24] “Government at a Glance 2023 Country Notes: Finland,” OECD, June 30, 2023, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/government-at-a-glance-2023_c4200b14-en/finland_d1080a88-en.html; Esa Reunanen, “Finland,” in Reuters Institute: Digital News Report 2024, eds. Nic Newman et al. (Oxford: University of Oxford Reuters Institute, June 14, 2023), 78, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2024-06/RISJ_DNR_2024_Digital_v10%20lr.pdf.

- [25] Pat Condo, “Just 3 States Require Teaching Media Literacy. Growth of AI Makes It Essential,” The 74, October 10, 2023,https://www.the74million.org/article/just-3-states-require-teaching-media-literacy-growth-of-ai-makes-it-essential/.

- [26] Friedel Weinert, “The Role of Trust in Political Systems. A Philosophical Perspective,”

Open Political Science 1, no.1 (2018): 8, https://doi.org/10.1515/openps-2017-0002. - [27] Aaron Blake, “The tempest over DHS’s Disinformation Governance Board,” Washington Post, May 02, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/04/29/disinformation-governance-board-dhs/.

- [28] Federal Election Commission, “REG 2023-02 (Artificial Intelligence in Campaign Ads) – Draft Notice of Disposition,” September 10, 2024, https://sers.fec.gov/fosers/showpdf.htm?docid=425538.

- [29] Coordinated inauthentic behavior, or CIB, is a manipulative communication tactic that uses a mix of authentic, fake, and duplicated social media accounts to operate as an adversarial network across multiple social media platforms with the goal of deceiving other platform users. See: Rowan Ings and Renee DiResta, “How Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior continues on Social Platforms,” Stanford University Cyber Policy Center, May 29, 2024,

https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/io/news/how-coordinated-inauthentic-behavior-continues-social-platforms. - [30] Sarah Fioroni, “Local News Most Trusted in Keeping Americans Informed About Their Communities,” Gallup Polling and the Knight Foundation, May 19, 2022,

https://knightfoundation.org/articles/local-news-most-trusted-in-keeping-americans-informed-about-their-communities/. - [31] Shari R. Veil, Tara Buehner, and Michael J. Palenchar, “A Work-In Process Literature Review: Incorporating Social Media in Risk and Crisis Communication,”

Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 19, no.2 (2011): 110-122, 114, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2011.00639.x. - [32] Vijay Balasubramaniyan, “Pindrop Reveals TTS Engine Behind Biden AI Robocall,” Pindrop, January 25, 2024, https://www.pindrop.com/blog/pindrop-reveals-tts-engine-behind-biden-ai-robocall.

- [33] Federal Communications Commission, Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 (FCC 24-60), May 28, 2024,

https://web.archive.org/web/20240529005353/https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-24-60A1.pdf; Federal Communications Commission, Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 (FCC 24-59), May 24, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240902064335/https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-24-59A1.pdf. - [34] “Update to our policy on Disclosure requirements for synthetic content (July 2024),” Google, July 01, 2024, https://support.google.com/adspolicy/answer/15142358?hl=en

. - [35] “Synthetic and manipulated media policy,” X, April 2023, https://help.x.com/en/rules-and-policies/manipulated-media.

- [36] Valerie C. Brannon and Eric N. Holmes, Section 230: An Overview (Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, January 04, 2024), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46751.

- [37] “Social Media and News Fact Sheet,” Pew Research Center, September 17, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/.

- [38] Eric Simpson and Adam Conner, “How To Regulate Tech: A Technology Policy Framework for Online Services,” Center for American Progress, November 16, 2021,

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-to-regulate-tech-a-technology-policy-framework-for-online-services/. - [39] “A Tech Accord to Combat Deceptive Use of AI in 2024 Elections,” Munich Security Conference, February 16, 2024, https://securityconference.org/en/aielectionsaccord/.

- [40] Kyle Wiggers, “Anthropic takes steps to prevent election misinformation,” TechCrunch, February 16, 2024, https://techcrunch.com/2024/02/16/anthropic-takes-steps-to-prevent-election-misinformation/.

- [41] “Social Media and News Fact Sheet,” Pew Research Center, September 17, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/.

- [42] Kyle Wiggers, “Anthropic takes steps to prevent election misinformation,” TechCrunch, February 16, 2024, https://techcrunch.com/2024/02/16/anthropic-takes-steps-to-prevent-election-misinformation/.

(Photo Credit: smartboy10 / Getty Images)

A dangerous confluence: The intertwined crises of disinformation and democracies: Contents

Introduction

The Definition and Purpose of Disinformation / Democratic Backsliding / Why Should We Care About Disinformation in an Era of Democratic Crisis? / Three Risks of the Spread of Disinformation and Democratic Backsliding / Report Structure

Chapter 1 Hungary: Media Control and Disinformation

Democratic Backsliding: Increased Control over Information Sources Through Media Acquisitions / Disinformation Through the Media and Its Impact: The Refugee Crisis / The Russia-Ukraine War: The Import and Export of Disinformation / The Negative Impact of Disinformation

Chapter 2 Disinformation in the United States: When Distrust Trumps Facts

The Early Years of American Disinformation: / The American Context: Distrust, Past and Present / The Challenge for Newsrooms / Managing Disinformation Through the Spreader & Consumer

Chapter 3 The Engagement Trap and Disinformation in the United Kingdom

Dragging Their Feet: Initial Slow Response to the Disinformation Threat / The Engagement Trap / A New Level of Threat to Democracy / Combatting Disinformation

Conclusion: Disinformation in Japan and How to Deal with It

Disinformation During Elections and Natural Disasters in Japan / Disinformation Policies During Crises: The 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election as Case Study / Disinformation During Crises: The Noto Peninsula Earthquake and Typhoon Jebi / Policy Recommendations

Disclaimer: Please note that the contents and opinions expressed in this report are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the International House of Japan or the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG), to which the authors belong. Unauthorized reproduction or reprinting of the article is prohibited.

Research Associate

Marina Dickson earned her Master of Arts in Strategic Studies and International Economics with a minor in Korea Studies from the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University. At SAIS, she worked as a Research Assistant under Dr. Thomas Rid focusing on disinformation and information security. Prior to her Masters, she worked at the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies as a Policy Research Fellow under Dr. Kent Calder. She also has experience working as a senior consultant at The Beacon Group, supporting Fortune 500 companies in defense, technology, and healthcare industries navigate new market opportunities. She holds a Bachelor of Arts from Bates College in Politics and History.

View Profile-

Japan’s Sea Lanes and U.S. LNG: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.02.24

Japan’s Sea Lanes and U.S. LNG: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.02.24 -

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09