Final Chapter: Disinformation in Japan and how to deal with it

In Chapter One, we looked at Hungary which has arguably experienced the most severe levels of democratic backsliding over the past decade. In Hungary, the Orbán government has been accused of strengthening its influence over formerly independent media through steadily tightening regulations by introducing legislative amendments and purchasing ownership. Additionally, quantitative analysis was presented of how both the disinformation from Russia and disinformation and conspiracy theories from Hungary itself are facilitating both an import and export of disinformation in the case of Hungary.

Chapter Two analyzed the relationship between disinformation and democratic backsliding in the United States. The chapter outlined the history of disinformation in the United States and how both external and internal forces have contributed to the spread of disinformation. With trust in public institutions and media at a historic low, the domestic environment is acutely vulnerable. Distrustful citizens are prime targets of disinformation campaigns and malicious actors from inside or outside the country can strategically target such citizens. To combat disinformation, the chapter argued that a multi-pronged approach including the federal and local governments, the media, major technology companies, and public education must all play a role in reducing the effects of disinformation.

Chapter Three investigated the case of the United Kingdom and how it struggled with the threat of disinformation from both external and internal forces similar to the United States, but has managed to remain resilient to the threat with its relatively low levels of public polarization and a respected and independent media. The “engagement trap”, as exemplified in the “£350 million” claim which was used in the 2016 EU referendum by the Vote Leave campaign, is a disinformation tactic which twists the truth by utilizing emotionally engaging material to maximize engagement that ultimately leads to the spread of disinformation. The “engagement trap” is thus resistant to attempts at fact-checking, and presents a dilemma even for countries with strong democratic institutions. The chapter briefly introduced some of the UK policy responses, and concluded by arguing that grassroots organizations such as NAFO were particularly adept at weaponizing the “engagement trap” by using humor as a tool against disinformation.

Drawing from the findings of these three case studies, we now present four generalizable findings in this chapter. First, it is critical to assess the state of the media by checking its independence through the existence or absence of government regulations. Second, there needs to be a clear distinction made between how disinformation is being spread in times of crises and times of calm. Third, users should check whether they are in danger of being captured by the “engagement trap”. Fourth, it is important to understand the degree of public trust towards key democratic institutions (elections, the executive, the judiciary, and the media) as well as levels of political polarization.

In this chapter, we apply the four generalizable findings from above (with a particular focus on the first three) to the case of Japan. We provide a general overview of the current state of disinformation in Japan, with a specific focus on the differences between disinformation spread in times of crisis (natural disaster) and calm (elections). We conclude by presenting five policy recommendations for Japan which we drew from the three case studies and takes into account the unique situation in the country.

Disinformation During Elections and Natural Disasters in Japan

Japanese experts on disinformation generally agree that at present, disinformation campaigns orchestrated by external forces remain relatively limited in both scale and influence in Japan. Ichihara argues that “[p]olitical maneuvering through disinformation has been somewhat restrained thus far in Japan”.[1] Kuwahara echoes this sentiment by noting that Japan has yet to experience a serious disinformation campaign from abroad, in contrast to what is happening in the West.[2] Kawaguchi is more assertive in his conviction that there is so far no evidence to suggest that a foreign power has conducted a large-scale and online disinformation campaign during a Japanese election.[3] While they may differ in terms of expression, there is thus a general consensus within the academic sphere that Japan has so far been shielded from organized foreign disinformation campaigns.

This does not mean that the threat of the spread of disinformation does not exist in Japan. Yet, Japan has so far managed to buck the trend by containing the threat of disinformation. One potential reason behind this is the relatively high levels of trust bestowed on the Japanese mass media, in addition to the lack of substantive differences in terms of policy between political party policies. For example, according to the Smart News Media Research Institute, 67 per cent of liberals and 69 per cent of conservatives in Japan trust the media.[4] Another possible reason for the contained threat of disinformation is arguably Japan being a relatively stable democracy. Despite problems such as low levels of citizen participation, Japan is considered one of the most stable democracies in Asia according to the Democracy Index.[5]

To reiterate, this does not mean that there will not be threats of disinformation in the future. First, as mentioned above, public trust towards the media is relatively high, but this is steadily eroding among the younger generations. The same study by the Smart News Media Research Institute found that trust towards the media is highest among the most senior citizens (those over 60) standing at 81 per cent.[6] Among those aged 40-59 trust is at 71 per cent, and among the younger generation (those under 39) it plummets to just 56 per cent. Second, the fact that political news is consumed as a form of entertainment, especially those that are aired on commercial broadcasting stations, is a unique issue in Japan. There are concerns that in the public eye, there is no clear distinction between investigative journalism and personal news blogs.[7]

As the cases of Hungary and the United States have shown, elections are an ideal time for disinformation and misinformation to spread. In the case of Japan, there were signs of a particularly high volume of disinformation and misinformation during the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election that strategically targeted specific candidates. As noted in the introductory chapter, the spread of disinformation during elections poses the danger of delegitimizing the electoral results, and remain a concern for Japan. Additionally, Japan is a country prone to natural disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons that have devastating consequences for the communities affected. While disinformation and misinformation are known to spread during disasters, recent years have witnessed cases of foreign actors spreading misinformation during times of crisis.

The following sections are split between times of calm and times of crises and analyze disinformation tactics during each situation. The first section explores the disinformation and misinformation spread during the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election, followed by an analysis of how disinformation and misinformation were spread during natural disasters, and how the Japanese government and the Japanese media responded. In the case of Japan, since the development of policies against disinformation at the national level is still ongoing, unlike the three case studies presented in this report, we focus on the regional level response.

Disinformation Policies in Calm Times: The 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election as Case Study

Gubernatorial elections are held in Okinawa once every four years, but the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election was called earlier than expected following the sudden death of Governor Takeshi Onaga. While then-candidate Denny Tamaki from the Liberal Party led the race with the backing of the “All Okinawa” anti-U.S. military base group (which also supported Governor Onaga). The competition quickly turned into a two-horse race between Tamaki and the mayor of Ginowan City, Atsushi Sakima, who received backing from the Liberal Democratic Party, Komeito, and the Japan Innovation Party. Since a third of the voters remained undecided, the political struggle reached fever pitch.[8]

It also saw the considerable spread of disinformation. For example, there was a survey conducted that purported to be by the Asahi Shimbun, a major Japanese newspaper saying that “one candidate scored 52 per cent favorability, while the other received just 26 per cent favorability”. The Asahi Shimbun itself denies that such a survey was conducted by them, calling it “a groundless accusation” and stating that “these numbers are not produced by us, and we did not commission any surveys”. Another survey which claimed to have been commissioned by the Democratic Party For the People (DPP) claimed that “one candidate was leading another by 13 points”, but the DPP itself denied the existence of such a survey, stating that “we cannot verify that any survey was done by us, and neither have we given permission for one to be conducted”.[9]

In comparison to the U.S. and U.K. cases, the Japanese mass media rarely includes source links in their articles (a trait it shares with Hungarian traditional media). This poses a serious problem as just 26.1 per cent of Japanese respondents said they made the effort to verify the credibility of information they are either uncertain about or do not trust.[10] This was a much more common practice among Americans (50 per cent) and relatively more British respondents said they would do this (38.2 per cent)[11], indicating that the Japanese are comparatively less likely to search for the original information. However, the difficulty in gaining access to such information is arguably making it more difficult to assess the accuracy of information more generally.

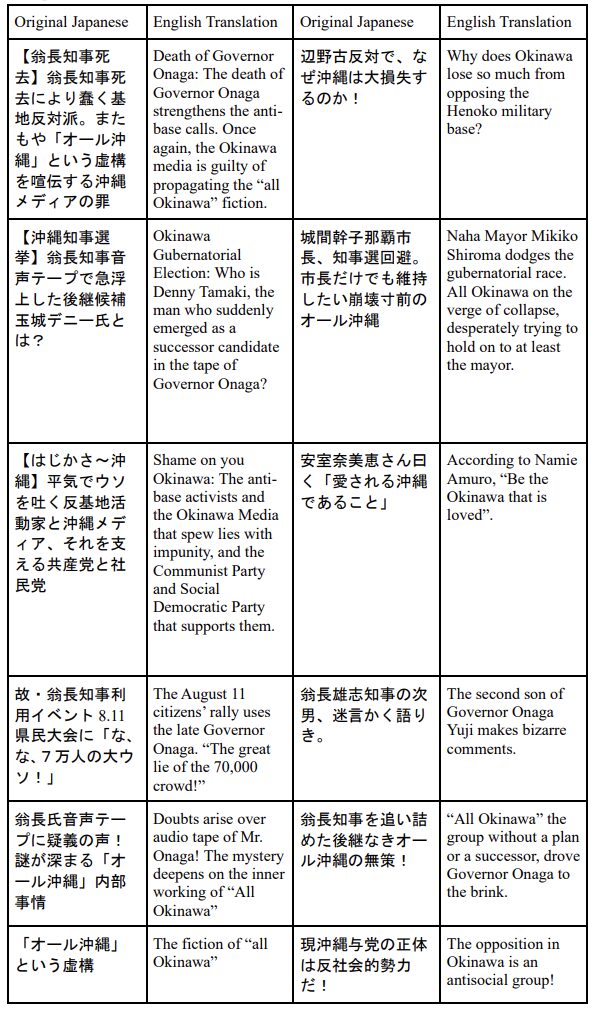

Fake websites such as “沖縄県知事選挙2018.com (Okinawa Gubernatorial Election 2018.com)” were set up with seemingly the sole purpose of attacking specific candidates and have since been taken down. The name of the website itself gave the impression that it was an official resource and at one point it managed to come at the top of the search results and was spread widely on social media. However, aside from the section that shared historical election results, most of the posts on the website were defamatory, especially against Denny Tamaki, describing him as an “anti-Japanese radical left-winger who will lie and use violence” and claimed that “Denny Tamaki is already infringing electoral law”.[12] In Table 4-1, we list all the post titles from this website, which shows how the posts nearly exclusively talk about Denny Tamaki.

Local media such as the Ryukyu Shimpo and the Okinawa Times created special issues dedicated to investigating the issue of the fake website, conducted fact checking, and made efforts to track the original source of the disinformation.[13] While Ryukyu Shimpo journalists visited an address in Tokyo that was listed in the domain information, they were unable to make contact with the owner.[14] The website did not contain any advertisements, and the same individual owned another website called “沖縄基地問題.com (Okinawa Military Base Issue.com)”[15],suggesting that it is unlikely that the website was made to make profit from online engagement (what is known in Japanese as an “impression zombie”), and instead was likely created to achieve a political purpose.

But the experience of local media in this case underscores the difficulty of the disproportionate cost/reward ratio involved in fact-checking work. According to one study, out of the 65 unverifiable claims collected by the Okinawa Times, just two made it to print.[16] One journalist complained that fact checking takes tremendous effort, more than writing a normal news article, and the disproportionate effort entailed brings little reward.[17] This reflects the limited resources local newspapers have at their disposal, not least of all in terms of staff. Discussions during committee meetings organized by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications specifically identified the spiraling costs of trying to verify information online as a problem.[18] The case of the spread of disinformation during the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election and the local media’s efforts at debunking them is a prime example of such concerns.

Disinformation may potentially uniquely be destabilizing for democratic institutions in geopolitically sensitive places like Okinawa. It is evident from this case that closer cooperation is needed not just between social media platforms and fact checkers (as was the case between Hearst Communications and FacCheck.org as mentioned in Chapter Two), but also between local media and NGOs, where greater cooperation will lead to a better pooling of resources.

Table 1: List of post titles from “沖縄県知事選挙 2018.com [Okinawa Gubernatorial Election 2018.com]”.

(Source: Author)

(Source: Author)

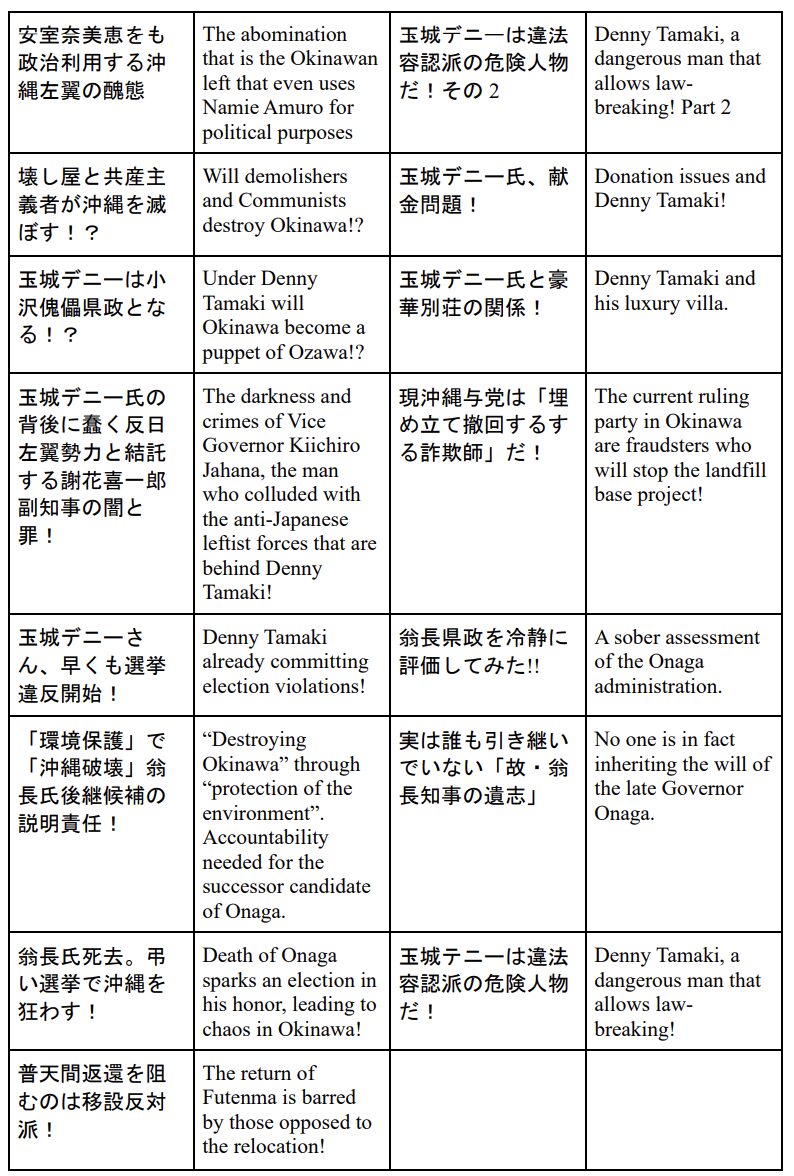

Figure 1: Word cloud of the post titles from the “沖縄県知事選挙 2018.com [Okinawa Gubernatorial

Election 2018.com]”. (Source: Author, based on “沖縄県知事選挙 2018.com”)

(Source: Author, based on “沖縄県知事選挙 2018.com”)

Disinformation During Crises: The Noto Peninsula Earthquake and Typhoon Jebi

Japan is prone to natural disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons, and it has a long history with the spread of disinformation- and misinformation during such times of crisis. In the recent earthquake on the Noto Peninsula in January 2024, disinformation was circulated claiming that gangs of foreign robbers were at large was widely spread online.[19] There is also evidence to suggest that such disinformation is being spread by foreign accounts.[20] These efforts are usually made with the goal of making a profit, which in turn means that they often target accounts that have more than 500 followers on X (formerly known as Twitter) and posts with more than five million viewers within three months.[21]

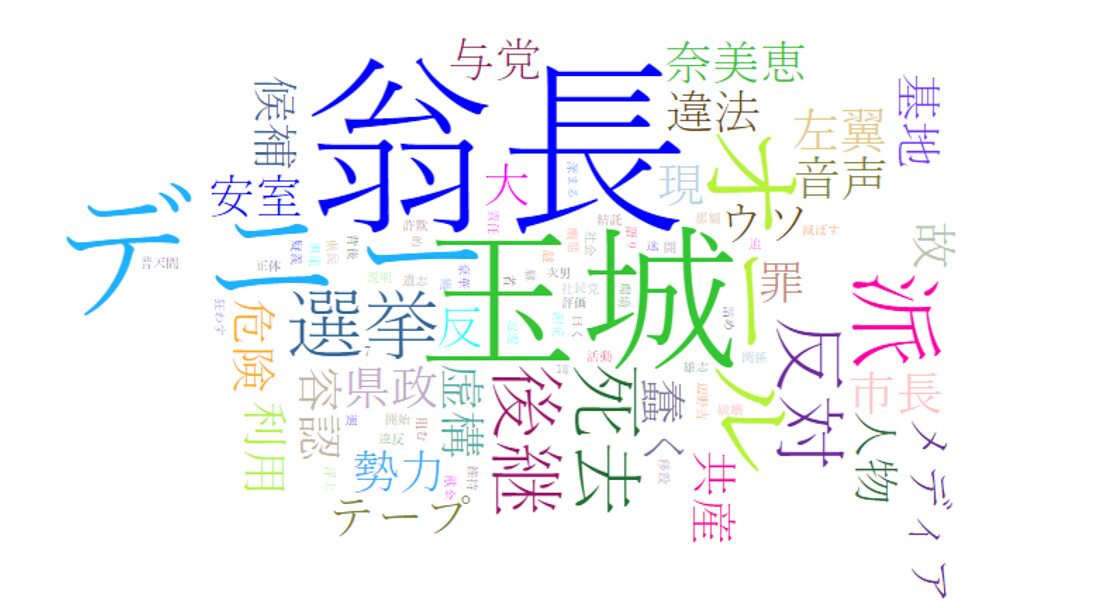

Disinformation that is circulated after a natural disaster is not a problem which is exclusive to Japan. Audiences in Taiwan were targeted in 2018 when the Kansai International Airport was forced to close down as it was flooded by Typhoon Jebi and a tanker collision with a connecting bridge, resulting in around 8,000 people finding themselves temporarily stranded at the airport. Disinformation began to circulate claiming that Chinese citizens were being given priority and being rescued by buses provided by the Chinese consulate. The disinformation included strong praise towards China and harsh criticism against Taiwan, even leading to Su Chii-cherng, the representative of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Osaka, committing suicide. Troublingly, Taiwan’s news media were slow to respond to the spread of disinformation, with Taiwan FactCheck Center taking 15 days to debunk the disinformation, around the time when they were having active collaboration with a Japanese NGO over disinformation.[22] While it remains unclear where the disinformation came from, some have argued that it may have originated from mainland China[23] given that it was first circulated in mainland China before it reached Taiwan, and how it was spread just a month before Taiwan’s local elections. In response, Taiwan FactCheck Center, which was at first intended to be a temporary establishment, was quickly made permanent.[24]

Table 2: Disinformation during the closure of the Kansai International Airport.  (Source: Author, based on Watanabe (2024))

(Source: Author, based on Watanabe (2024))

<Column>Pub talk and Ryukyu independence: the Chinese disinformation swirling around the treated waters from Fukushima

Talks of Ryukyu independence have a long history. Ever since the Ryukyu-Han was abolished on March 27, 1879, and the annexation of Ryukyu (to be made the Okinawa Prefecture), there have been rumblings of Ryukyu independence across some quarters. Most of the Ryukyu independence talks center around questions over whether or not it is right to become independent, and what will happen if it is to go ahead with such plans.[26] As it were, at present these talks are mere pub talks, and there is yet to be a serious movement for independence. However, there are some that argue that such talks over Ryukyu independence has been used by China to divide public opinion in Japan.

Influence operation is defined as “limiting information to manipulate or confuse understanding and judgements of the target country into acting in a way that is beneficial to them”.[27] For example, a report published by the Public Security Intelligence Agency argued that China is getting in touch with organizations and researchers who research the Ryukyu independence movement, and that China has published multiple essays that are sympathetic to the cause.[28] One such article was an editorial piece published in the Global Times in August 2017, titled “How Ryukyu should not be called Okinawa: Questions over where Ryukyu belongs”. Such arguments that claim that Okinawa’s position remains an “unresolved issue” coincided with the publication of articles such as “Activating the Ryukyu issue to pave the way for changing the official position” (from the Global Times),[29] and “Return the Diaoyu Islands to China, the time has come for a renegotiation of Ryukyu” (People’s Daily),[30] that were published at a time when the Senkaku Island debate was accelerating. The Public Security Intelligence Agency warns that such articles are part of a wider Chinese scheme to foster public opinion in Okinawa that is favorable to China and create divisions within Japan.[31]

More recently, on May 13, 2023, during a meeting with the LDP, a former Chinese military official challenged participants by asking “Ryukyu is originally a Chinese territory, but how would you feel if it were to declare independence?”.[32] On May 26, 2023, Yang Bojang the head of Japanese Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences commented at a forum held in Japan that “We need to review the San Francisco Peace Treaty [which returned Okinawa to Japan]”.[33] In the following month then newly sworn in Xi Jinping emphasized the historically deep ties between China and the Ryukyu, which was the first time he spoke out on the topic since coming into power.[34]

There is nothing new about Okinawa’s vulnerabilities against Chinese disinformation campaigns. In a 2018 report by RAND, it was pointed out that resentment towards the United States’ military base in Okinawa presents possible vulnerabilities against Chinese information operations.[35] While the focus in the past has been that of spreading favorable popular and academic narratives on China, there has been new large-scale disinformation campaigns on social media such as the ones on the release of the ALPS-treated water.[36]

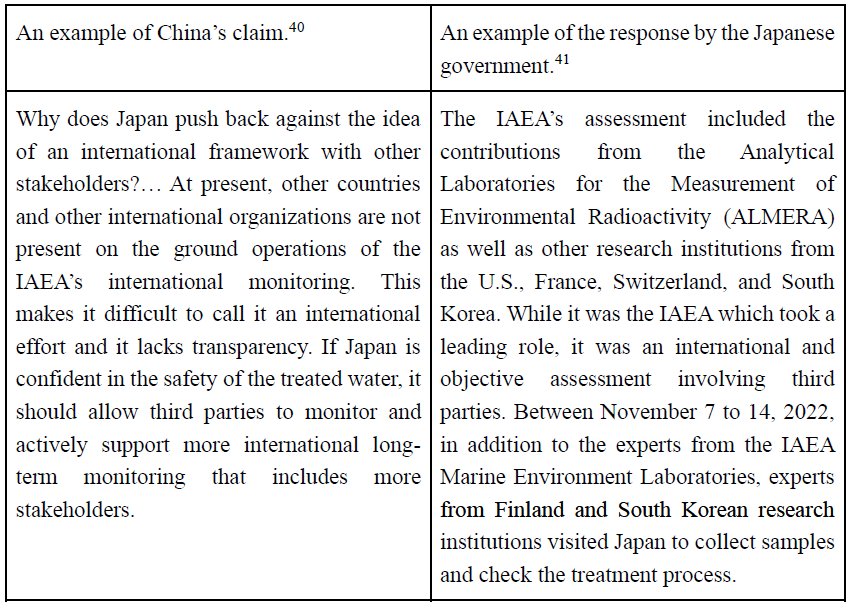

Given that the IAEA and the scientific community agree that the impact of the release of the ALPS-treated water is limited, Tepco took the decision to release the ALPS-treated waters from August 2023. The Chinese embassy in Japan press office issued comments on the Chinese government’s position regarding the ALPS-treated water on its website.[37] The Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by issuing a statement titled “Response to comments made by the Chinese government regarding the ALPS-treated water discharge into the sea” and argued that the Chinese claims lacked factual as well as scientific evidence.[38] See Table 3 below for the actual comments made by both sides.

Table 3: Disinformation and factcheck related to the release of the ALPS-treated water from Fukushima. (Source: Author, based on explanations of Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan and Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

(Source: Author, based on explanations of Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan and Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

Regarding the release of the ALPS-treated water into the sea, there were social media posts that contained disinformation such as the claim that 20,000 fish intended to China were instead sold to Taiwan, or that Japan donated money to the IAEA, and that the radioactivity levels in the treated water exceeded standard levels. Chinese state-owned media actively sent out paid advertisements on social media sites that proclaimed the dangers of the treated water in not only English and German, but also in Khmer (language native to Cambodia) which indicates its desire to spread the information both internationally as well as in Asia more specifically.[41]

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Japan tried to combat these disinformation claims on social media by using both its Japanese and English social media accounts. It used hashtags such as #STOP風評被害 (#STOPtheRumors) and #LetTheScienceTalk, which were accompanied by explainers of the lithium concentration standard levels using graphs and videos as well as images and bullet points of research findings in an attempt to tackle the issue. In addition, it tried out new campaigns such as using #BeautyofFUKUSHIMA to advertise Fukushima and its food.[42] As mentioned in Chapter Three, organizations such as NAFO have tried to tackle the threat of disinformation by making fun of Russian disinformation regarding Ukraine through the use of memes and humor. #BeautyofFUKUSHIMA is an example of positive posts on a social media platform being used as a diplomatic tool. This is of particular importance considering how negative content tends to dominate social media.

Policy Recommendations

The three case studies described in this report provide crucial insight for the Japanese government and media for developing an effective policy response against disinformation. In this section, we provide five policy recommendations developed based on a case study approach of Hungary, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

[General Policy Recommendation]

1. Wider acknowledgement of the serious threat to democratic institutions and norms posed by disinformation. In particular, awareness that both domestic and foreign actors will try to spread disinformation during elections and times of political crises in hopes of destabilizing democracies (corresponding chapters: Chapters One to Three).

As the United States (Chapter Two) and Japan (Chapter Four) show, election periods are a particularly vulnerable period for democracies as foreign governments as well as domestic groups and individuals may try to spread disinformation. While much of the focus is on national elections, local elections can also be targets of such attacks. As Chapter One showed, the spread of disinformation can occur during international crises such as the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe and Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. However, it can also be spread during domestic crises such as earthquakes and typhoons as this chapter discussed. While the common disinformation tactic is to target specific politicians or political parties, during domestic crises this could be done for commercial purposes as well as political purposes. Regardless of motivation, such disinformation tactics lead to polarization and erode public trust towards key democratic institutions such as elections, the legislature, the judiciary, and the media.

2. Conventional fact checking is insufficient to avoid the “engagement trap”. There should be greater openness towards different kinds of strategies such as the use of memes and humor to weaponize the “engagement trap” may be needed (corresponding chapter: Chapter Three).

Chapter Three defined the term the “engagement trap” as a “disinformation tactic which twists the truth and makes it emotionally engaging to maintain maximum engagement with the aim of spreading a narrative that is beneficial to the perpetrator”. The chapter argued that while fact checking is essential to tackling disinformation, it also carries the danger of unwittingly amplifying the disinformation itself. This is why it is important to try to weaponize the “engagement trap” by using memes and humor, in the manner of grassroots organizations such as NAFO. Additionally, this chapter argues that #BeautyofFUKUSHIMA is another example of the use of positive hashtag campaigns.

[Policy Recommendation for the Government]

3. The Japanese government should not take reporting from foreign sources at face value, but instead assess the position of each source against the context of the source country, including the levels of press freedom and any political or economic motivations behind it. For example, the politics division within embassies should improve their ability to gather data and perform analysis and consider publishing parts of their findings to the public as a way of tackling disinformation (corresponding chapter: Chapter One).

Chapter One argued that Hungarian media is increasingly under the influence of the Hungarian government, which presents a potential risk of the spread of disinformation. This is a common problem in countries that face democratic backsliding. There is no guarantee that media outlets once renowned for their independence may be able to maintain that independence, and even those that may at first seem independent may not necessarily be so in practice. The Hungarian case exemplifies the importance of considering the political and economic background of the media itself, but to make such assessments institutions such as embassies will play a critical role given their strong knowledge of the countries where they are located. As others have argued,[43] the political divisions within embassies could help gather and assess data and publish at least parts of their analyses to help educate the public on the democratic conditions of given countries with the goal of debunking the spread of disinformation related to those countries.

[Recommendations on anti-disinformation policies during crises for the government]

4. Government regulations against disinformation should also assess policy changes abroad. While anti-disinformation policy needs to be pragmatic and ensure freedom of expression, there should be considerations of the broader impact of disinformation on personal safety and democracy (corresponding chapters: Chapters Two & Three). In particular, the government should work towards the swift introduction of the prominence rule to allow for the public media to be given priority coverage on tv and social media in anticipation of an influx of disinformation during crises. They should additionally consider placing a temporary limit on accessing such media (corresponding chapter: Chapter Three).

As argued in Chapters One and Two, the spread of disinformation can lead to public distrust towards the government and the media, thus risking the erosion of democratic norms. While discussions over anti-disinformation policy are inevitably a balancing act with the value of freedom of expression, these discussions should be broadened to include considerations of potential threats to personal safety and democracy itself. Public anxiety during natural disasters and international crises can create environments especially receptive to disinformation. As Chapter One demonstrated, crises such as the Russia-Ukraine War can lead to the spread of disinformation at an organizational level. We argue that one solution may be to introduce something similar to the United Kingdom’s prominence rule, which prioritizes the reporting of trusted sources such as public media in TV. This policy could be extended to other platforms such as social media, something that Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications is already considering.[44] Additionally, concerns over the spread of disinformation through foreign state-controlled media should lead to at least some consideration over restricting access to it as was the case in the United Kingdom following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see Chapter Three).

[Build a framework against disinformation in government, newspapers, and fact check organizations]

5. To improve the reliability of information, the government should establish a framework that enables society as a whole to bear the costs of debunking disinformation (corresponding chapters: Chapters Two and Three).

➢ 5-1 In addition to large tech firms and fact checking groups, there should be a framework that includes not only major media firms and major press, but also local media and press that may have limited resources.

➢ 5-2 To make verification easier, each organization targeted by disinformation should provide and disseminate a database that provides a summary of debunked disinformation.

➢ 5.3 The media should provide the URLs of original sources in their reporting where possible.

While it is widely acknowledged that large tech firms and fact checking groups will play a leading role in ensuring the spread of reliable information and providing fact checks, as the example of the BBC Verify in Chapter Three indicated, large media firms will particularly play a critical role in offering fact checks. Additionally, as mentioned in Chapter Two, there are cases in which local print media are more trusted than national ones. In Japan, local media particularly play a key role in reporting on local elections and natural disasters. Based on this, local media as well as major media firms should be actively incorporated in the formation of a framework dealing with disinformation. Such a framework should focus on effectively utilizing fact checking tools being developed by media in the United States and United Kingdom, as well as by social media providers.[45] There should be a further focus on expanding the database of fact checks, making it accessible not only to experts but also regular citizens. Following the introduction of the Link Attribution Protocol in the United Kingdom, there needs to be greater effort to add the URLs of original sources in media reporting, making it difficult to create fake polling data as was the case in Okinawa, and to help improve the transparency and reliability of information.

footnote

- [1] Maiko Ichihara, “Influence Activities of Domestic Actors on the Internet: Disinformation and Information Manipulation in Japan,” in Social Media, Disinformation, and Democracy in Asia: Country Cases, ed. Asia Democracy Research Network (Seoul: Asia Democracy Research Network, October 2020), 1-19, 2.

- [2] Kyoko Kuwahara, 外交と偽情報―ディスインフォメーションという脅威 [Diplomacy and Disinformation: The threat of disinformation], in 偽情報戦争―あなたの頭の中で起こる戦い [The Disinformation War: The war that wages in your mind], eds. Yu Koizumi, Kyoko Kuwahara, and Kouichiro Komiyama (Tokyo: Wedge, 2023), 16-49, 32.

- [3] Takahisa Kawaguchi, “外国政府による選挙干渉とディスインフォメーション [Electoral Interference and Disinformation from Foreign Governments],” in ハックされる民主主義:デジタル社会の選挙干渉リスク [Hacked Democracy: Risks of Electoral Interference in the Digital Society], eds. Motohiro Tsuchiya and Takahisa Kawaguchi (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 2023).

- [4] Smart News Media Research Institute, 第1回 スマートニュース・メディア価値観全国調査メディア向けシンポジウム資料 [First Smart News Media Values National Survey: Symposium for the Media] (Tokyo: Smart News Media Research Institute, November 24, 2023), https://web.archive.org/web/20240813074635/https://smartnews-smri.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/231124_SMPP.pdf.

- [5] “Democracy Index: conflict and polarisation drive a new low for global democracy,” Economic Intelligence Unit, February 25, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240812213234/https://www.eiu.com/n/democracy-index-conflict-and-polarisation-drive-a-new-low-for-global-democracy/.

- [6] Makoto Shiono, How to deal with influence operations in the era of generative AI, (Tokyo: Institute of Geoeconomics, April 21, 2024), https://apinitiative.org/GaIeyudaTuFo/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Geoeconomic_briefing_187.pdf.

- [7] Okinawa Times, “玉城氏リード、佐喜真氏が激しく追う 沖縄知事選・情勢調査 [Tamaki Leads, Yet the Competition Escalates with Sakima: Survey on the Okinawa Gubernatorial Election],” Okinawa Times, September 23, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20210516212706/https://www.okinawatimes.co.jp/articles/-/318998.

- [8] Akiko Kuwahara, “虚構のダブルスコア 沖縄県知事選、出回る「偽」世論調査 [The false double score: “Fake” Surveys Circulate in the Okinawa Gubernatorial Election],” Ryukyu Shimpo, September 8, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20220322172020/https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-799272.html.

- [9] Akiko Kuwahara, “虚構のダブルスコア 沖縄県知事選、出回る「偽」世論調査 [The false double score: “Fake” Surveys Circulate in the Okinawa Gubernatorial Election],” Ryukyushimpo, September 8, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20220322172020/https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-799272.html.

- [10] Shizuma Naka, 国内外における偽・誤情報に関する意識調査:令和4年度国内外における偽・情報に関する意識調査より [Survey on attitudes towards dis- and misinformation in Japan and abroad: From a 2022 survey on attitudes towards dis- and misinformation in Japan and abroad], (Tokyo: Mizuho Research & Technologies, Ltd., May 25, 2023), 18, https://web.archive.org/web/20240310080838/https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000889637.pdf.

- [11] Ibid.

- [12] “沖縄県知事選挙2018.com [Okinawa Gubernatorial Election 2018.com],” Okinawa Gubernatorial Election 2018.com, last updated September 12, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20180910224429/http://xn--2018-ft5fu20i04next2xbx12a111c.com/a001.html.

- [13] For more detail, refer to works such as Ryukyu Shimpo Editorial Board, 琉球新報が挑んだファクトチェック・フェイク監視 [Fact checking by the Ryukyu Shimpo] (Tokyo: Kobunken, 2019).

- [14] Hisao Miyagi, “知事選に偽情報、誰が? 2サイトに同一人物の名前 正体を追うと・・・<沖縄フェイクを追う>① [Who spread disinformation during the gubernatorial election? Tracking down the person whose name appears on two websites <Chasing fake news in Okinawa> Part 1],” Ryukyu Shimpo, January 01, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20240706102925/https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-856174.html.

- [15] Ibid.

- [16] Fujihiro Hiroyuki, “フェイクニュース検証記事の制作過程〜2018年沖縄県知事選挙における沖縄タイムスを事例として〜[Fake news verification process: A case study from The Okinawa Times during the 2018 gubernatorial election],” Socio-Informatics 8, no.2 (2019):143-157, 150, https://doi.org/10.14836/ssi.8.2_143.

- [17] Ibid,151.

- [18] Study Group on Ensuring the Soundness of Information and Communications in the Digital Space, “デジタル空間における情報流通の全体像(案)[The outlook of information and communications in the digital space],” Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, February 05, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240206023229/https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000927156.pdf.

- [19] Asahi Shimbun, “「日本人称賛」言説の裏返しか 被災地で繰り返された外国人犯罪デマ [The flip side to the praise for the Japanese: The repeated disinformation of foreign criminals in Noto],” Asahi Shimbun, September 09, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20240523224951/https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASR964G7JR93UNHB001.html. NHK, ”地震後「外国系窃盗団が能登半島に集結」偽情報などSNSで拡散 [Disinformation that a gang of foreign robbers arrived in Noto Peninsula was spread on social media after the earthquake],” NHK, January 10, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240731061202/https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20240110/k10014316541000.html.

- [20] Sankei Shimbun, “収益目当ての便乗投稿「インプレゾンビ」横行 地震直後にSNSで偽救助要請、大半は海外 [The infection of the “impression zombies”: majority of the SOS on social media after the earthquake comes from foreign sources with the aim of profiteering],” Sankei Shimbun, March 01, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240802080144/https://www.sankei.com/article/20240301-ZNQQJ7BWAJICNMY7PMHBV3GEMA/.

- [21] Mainichi Shimbun, “能登半島地震、Xで津波や救助要請のデマ拡散 背景に広告収益 [Noto Peninsula earthquake: The spread of tsunami and SOS disinformation aimed at making ad revenue],” Mainichi Shimbun, January 02, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240426190414/https://mainichi.jp/articles/20240102/k00/00m/040/195000c.

- [22] Yenfu Liu, “「中国人優遇」の偽ニュースはなぜ生まれたか:関空の中国人避難問題、一連の事実を検証 [Why was the fake news proclaiming the prioritization of the Chinese was spread: Analysis of the Chinese evacuees issue at Kansai International Airport],” Toyo Keizai Online, September 21, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20240813081814/https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/238795?display=b.

- [23] Yomiuri Shimbun, “偽ニュース台湾動揺:「中国がデマ」対策強化へ [Disinformation Rocks Taiwan: Calls for tackling Chinese hoax strengthens],” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 14, 2018.

- [24] Masahito Watanabe, 台湾のデモクラシー-メディア、選挙、アメリカ [Democracy in Taiwan: The media, election, and the U.S.] (Tokyo: Chuko Shinsho 2024).

- [25] Ibid.

- [26] Hiden Suzuki, “中国の「沖縄独立工作」を問う=鈴木英生(オピニオン編集部)[Question Chinese disinformation of Okinawa Independence = Hidden Suzuki (Opinion Editorial Department)],” Mainichi Shimbun, July 12, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20240522015031/https://mainichi.jp/articles/20230711/k00/00m/040/001000c.

- [27] Shinji Yamaguchi, “中国の影響工作概観 ——その目標・手段・組織・対象 [Chinese disinformation tactics, its goals, modes, organizations, and targets],” National Institute for Defense Studies Commentary, no.288, December 8, 2023, https://www.nids.mod.go.jp/publication/commentary/commentary288.html.

- [28] Public Security Intelligence Agency, Annual Report 2016 Review and Prospects of Internal and External Situations (Tokyo: Public Security Intelligence Agency, January 2017), 23, https://www.moj.go.jp/content/001221029.pdf.

- [29] Global Times, “社评:激活琉球问题,为改变官方立场铺垫 [Editorial: Activating the Ryukyu issue to pave the way for changing the official position],” Global Times, May 10, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20240813083455/https://m.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnJAsNz.

- [30] People’s Daily, “人民日報:釣魚島歸中國 琉球也到可再議的時候 [Return the Diaoyu Islands to China, the time has come for a renegotiation of Ryukyu],” People’s Daily, May 08, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20240523082623/http://politics.people.com.cn/BIG5/n/2013/0508/c1001-21400715.html.

- [31] Public Security Intelligence Agency, Annual Report.

- [32] Sankei Shimbun, “「沖縄が独立すると言ったら?」…中国軍元幹部が日本側に不穏当発言 [“What if I said Okinawa will become independent?” … Inappropriate statement by the former Chinese military official to the Japanese],” Sankei Shimbun, May 27, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20240813081415/https://www.sankei.com/article/20230527-DRDJOXQSLZLC3ODZ5C6F4LSA7E/.

- [33] Hideo Suzuki, “琉球独立?中国が影響力工作 沖縄をコマにする大国意識 [Ryukyu Independence? Chinese influence operations and Great Power views, how it reduces Okinawa to a useful pawn],” Mainichi Shimbun, July 19, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20240813075359/https://mainichi.jp/articles/20230719/ddm/005/070/005000c.

- [34] Yomiuri Shimbun, “習近平氏が「琉球」に言及、中国との「交流深い」…沖縄の帰属巡り揺さぶりか[Xi Jinping talks of “close relationship” between Ryukyu and China in a move to further strengthen debates over Okinawa],” Yomiuri Shimbun, June 09, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20230610172317/https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/world/20230609-OYT1T50214/.

- [35] Scott W. Harold, Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, Jefferey W. Hornung, Chinese Disinformation Efforts on Social Media (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2018), 102, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR4300/RR4373z3/RAND_RR4373z3.pdf.

- [36] Yomiuri Shimbun, “「処理水「偽情報」がSNS拡散、外務省など明確に否定…防衛省の初代情報官「AI対応急務」 [Disinformation related to the ALPS-treated water spreads on social media: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs clearly denies this and the first minister of information from the Ministry of Defense declares “an immediate need to deal with AI”],” Yomiuri Shimbun, December 13, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231216081005/https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/national/20231213-OYT1T50055/.

- [37] “駐日中国大使館報道官、日本福島放射能汚染水海洋放出問題について立場を表明 [Chinese embassy spokesperson expresses its position on Japan’s Fukushima radioactive contaminated water discharge into the sea],” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan, last modified July 04, 2023, http://jp.china-embassy.gov.cn/jpn/jbwzlm/dsgxx/202307/t20230704_11107549.htm.

- [38] “ALPS処理水の海洋放出に関する中国政府コメントに対する中国側への回答 [Response to comments made by the Chinese government regarding the ALPS-treated water discharge into the sea],” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, September 01, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/press/release/press1_001548.html.

- [39] “呉江浩大使、福島の核汚染水海洋放出問題で日本側に厳正な立場を一段と明確に説明 [Ambassador Wu Jianghao further clarifies China’s firm position on the issue of Fukushima nuclear contaminated water being discharged into the sea to the Japanese],” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan, August 28, 2023, http://jp.china-embassy.gov.cn/jpn/dsdt/202406/t20240612_11430870.htm.

- [40] “Response to Comments Made by the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Discharge of ALPS Treated Water into the Sea,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, September 01, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press5e_000041.html.

- [41] Derek Cai, “Fukushima: China’s anger at Japan is fuelled by disinformation,” BBC News, September 02, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66667291.

- [42] NHK, “外交戦と偽情報 処理水めぐる攻防を追う [Diplomatic warfare and disinformation tracing the diplomatic spat over the treated water],” NHK, August 29, 2023, https://www.nhk.or.jp/politics/articles/feature/101764.html.

- [43] The Policy Research Council of the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, the Foreign Affairs Council, the Foreign Affairs Research Council, and the International Cooperation Research Council, “外交部会・外交調査会・国際協力調査会が「外交力の抜本的な強化を求める決議」を申し入れ [The Foreign Affairs Council, the Foreign Affairs Research Council, and the International Cooperation Research Council submits a “Resolution calling for a fundamental strengthening of diplomatic power”],” The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, May 28, 2024, https://www.jimin.jp/news/policy/208305.html.

- [44] “デジタル空間における情報流通の健全性確保の在り方に関する検討会 [Committee on the soundness and distribution of information in the digital space],” Ministry of Internal Affairs, last accessed August 19, 2024, https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/kenkyu/digital_space/index.html.

- [45] For example, Google Fact Check Tools.

(Photo Credit: 毎日新聞社/アフロ)

A dangerous confluence: The intertwined crises of disinformation and democracies: Contents

Introduction

The Definition and Purpose of Disinformation / Democratic Backsliding / Why Should We Care About Disinformation in an Era of Democratic Crisis? / Three Risks of the Spread of Disinformation and Democratic Backsliding / Report Structure

Chapter 1 Hungary: Media Control and Disinformation

Democratic Backsliding: Increased Control over Information Sources Through Media Acquisitions / Disinformation Through the Media and Its Impact: The Refugee Crisis / The Russia-Ukraine War: The Import and Export of Disinformation / The Negative Impact of Disinformation

Chapter 2 Disinformation in the United States: When Distrust Trumps Facts

The Early Years of American Disinformation: / The American Context: Distrust, Past and Present / The Challenge for Newsrooms / Managing Disinformation Through the Spreader & Consumer

Chapter 3 The Engagement Trap and Disinformation in the United Kingdom

Dragging Their Feet: Initial Slow Response to the Disinformation Threat / The Engagement Trap / A New Level of Threat to Democracy / Combatting Disinformation

Conclusion: Disinformation in Japan and How to Deal with It

Disinformation During Elections and Natural Disasters in Japan / Disinformation Policies During Crises: The 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election as Case Study / Disinformation During Crises: The Noto Peninsula Earthquake and Typhoon Jebi / Policy Recommendations

Disclaimer: Please note that the contents and opinions expressed in this report are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the International House of Japan or the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG), to which the authors belong. Unauthorized reproduction or reprinting of the article is prohibited.

Research Fellow,

Digital Communications Officer

Yusuke Ishikawa is Research Fellow and Digital Communications Officer at Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG). His research focuses on European comparative politics, democratic backsliding, and anti-corruption. He also serves as External Contributor for Transparency International’s Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, as Associate Research Fellow at the EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, and as Part-time Lecturer in European Affairs at the Department of Economics and Business Management, Saitama Gakuen University. Prior to his current roles, Research Associate at IOG and API, contributing to its translation project of Critical Review of the Abe Administration into English and Chinese. Previously, he has worked as Research Assistant for API's CPTPP program and interned with its Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Abe Administration projects. His other experience includes serving as a visiting research fellow at EUEOPEUM Institute, a full-time research intern at Transparency International Hungary, and as a part-time consultant with Transparency International Defence & Security in the UK. His publications include "NGOs, Advocacy, and Anti-Corruption" (In Routledge Handbook of Anti-Corruption Research and Practice, 2025) and A Dangerous Confluence: The Intertwined Crises of Disinformation and Democracies (Institute of Geoeconomics, 2024). He has been featured in national and international media outlets including Japan Times, NHK, TV Asahi, Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), Handelsblatt, Expresso, and E-International Relations (E-IR). He received his BA in Political Science from Meiji University, MA in Corruption and Governance (with Distinction) from the University of Sussex, and another MA in Political Science from Central European University. During his BA and MAs, he also acquired teacher’s licenses in social studies in secondary education and a TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Language) certificate. [Concurrent Positions] Associate Research Fellow, EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, Czechia External Contributor Consultant, Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, Transparency International Secretariat (TI-S), Germany Part-time Lecturer, Department of Economics and Business Management, Saitama Gakuen University, Japan

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08