Can the Trump Administration Address the U.S. Military’s Multi-Front Resource Dispersion?

*The original article in Japanese was published on January 29, 2025.

As intense fighting continues in Ukraine, uncertainty lingers in the Middle East, and military tensions rise in the Taiwan Strait, concerns are growing over the relative decline of U.S. power, which is engaged on all three fronts. During the first Trump administration, the U.S. military's force development goals shifted from having the capability to cope with two theaters to a capability that prioritizes a single theater, responding to one threat while focusing on deterrence on other fronts. The primary emphasis within this shift was on great power competition with China. However, in reality, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and turmoil in the Middle East, forward-deployed US forces in both regions have been significantly reinforced, and a fundamental shift toward focusing on China has not progressed well.

What have caused the stalled shift toward China amid great power competition? As the second Trump administration takes shape, this four-part series will delve deeply into the specifics of U.S. military strategy.

The Background of the Stalled Shift Toward the Posture against China

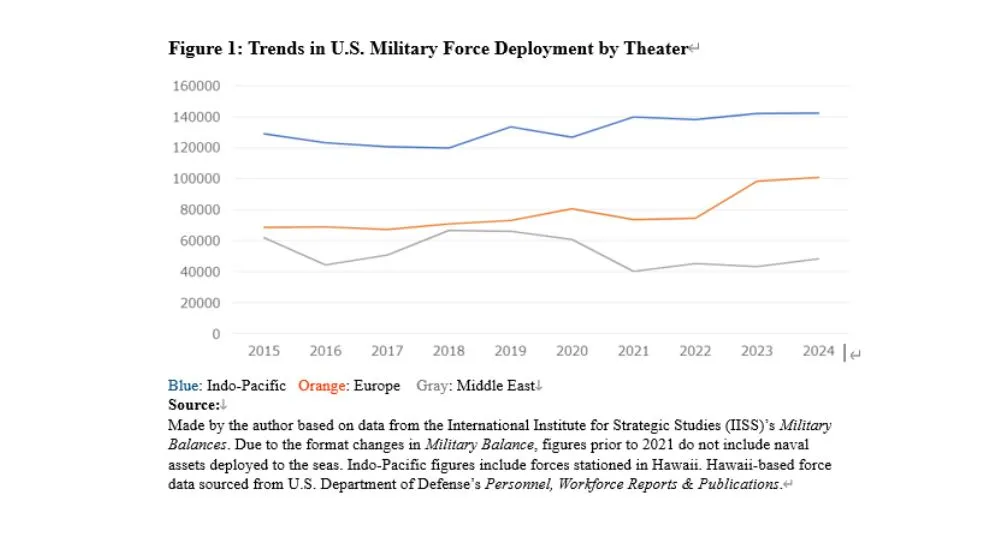

Despite the Biden administration inheriting the strategic objective set by the first Trump administration, and identifying China as “the most comprehensive and serious challenge,” the shift of U.S. military forces toward the Indo-Pacific—the primary theater for dealing with China—has not been proceeding smoothly. In response to the outbreak of the Ukraine war and the need to enhance readiness, the U.S. troop presence in Europe has increased by 25,000, now surpassing 100,000. Meanwhile, after bottoming out following the Afghanistan withdrawal, the U.S. military presence in the Middle East has started to rise again, almost reaching the 50,000 troops level. In contrast, the U.S. military presence in the Indo-Pacific region has consistently remained below 100,000 troops, and even when including the slightly increasing forces stationed in Hawaii, the total barely exceeds 140,000 (Figure 1).

Compared to the Chinese military, which reportedly has 420,000 ground troops, 257 naval vessels, and 1,240 operational aircraft in the Eastern and Southern Theater Commands alone, these numbers cannot be considered sufficient. At least, since China retains the world’s largest military, the fact that U.S. forces deployed in the Indo-Pacific are roughly equivalent in scale to U.S. forces in Europe—where 1.9 million NATO troops (excluding the U.S.) facing exhausted Russian troops—would not be a reasonable allocation of forces.

Four Factors Behind the Fixation of U.S. Resource Allocation

Why has this situation arisen? The answer involves four complex factors that go beyond a simple competition for defense resources.

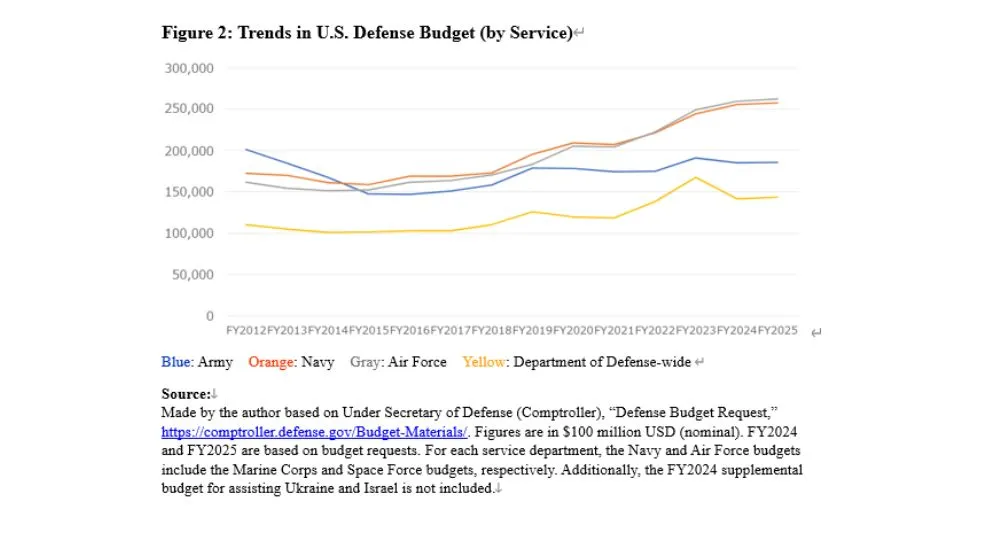

First, the U.S. defense budget, which is built from the bottom-up request by each service, has largely maintained its existing inter-branch distribution with little change (Figure 2).

While the Army’s budget has remained stable or slightly decreased and the Navy and Air Force budgets have seen modest increases, there have been no significant efforts to boldly shift resources from land-based forces to maritime and air forces—despite the fact that most operations involving China are expected to take place in the sea and air domains.

One contributing factor to this inertia is the cooperative division of labor among the branches. Each branch, keeping operations against China in mind, is focused on long-range precision strike capabilities, sensor-equipped systems, and the extensive use of unmanned assets, aiming for a distributed force posture. The goal has been not just to match China’s overwhelming numerical superiority but also to develop asymmetric denial capabilities, particularly in the maritime domain.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army, which would likely have a limited role in operations against China unless it fights on the ground conflict in Taiwan, has also sought to participate in great power competition beyond the land domain under the banner of “cross-domain operations.” Notably, this has not been challenged by other services, and a cooperative relationship has been maintained.

At the same time, the Army has preserved the size of its traditional Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) at 31 units for more than five years, allowing it greater flexibility to respond to current operational requirements in Europe and the Middle East compared to the Navy and the Air Force. Except scarce land assets such as air defense units, most Army assets are not the direct object of scrambles across multiple fronts, making it easier to deploy additional forces to Europe following the Ukraine war, such as the three additional BCTs and the establishment of the Fifth Corps’ forward headquarters. This stands in stark contrast to the tug-of-war over scarce assets like carrier strike groups. Ultimately, this status quo bias in resource allocation across services has contributed to the rigid force fixation across the three major theaters.

Second, the strong demand for forces from regional unified combatant commands has reinforced the balanced force allocation across the three fronts. The 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act, which inhibited the interference by the service chiefs to operations and strengthened the authority of regional combatant commanders, has played a crucial role in enhancing joint operational capabilities. However, it has also brought about unintended consequences.

One such consequence is that each combatant commander, whose primary mission is to address threats within their areas of responsibility, inevitably demands what they see as the necessary and sufficient resources to tackle those threats. A prime example is the frequent requests by successive Central Command (CENTCOM) commanders for carrier strike group deployments whenever tensions rise in their area of responsibility. These requests have become almost a routine occurrence.

Moreover, because these commanders can directly appeal to Congress in their testimony, the resulting budget often becomes a compromise that distributes resources across multiple theaters. It is difficult for civilian officials in the Department of Defense or lawmakers to vocally challenge this dynamic.

Third, in recent years, a mentality prioritizing enhanced readiness to address current threats over investment in capabilities for future threats—what might be called the “tyranny of the present”—has become increasingly evident.

While the U.S. National Defense Strategy (NDS) categorize China as a long-term but top-priority challenge, and Russia as an immediate but secondary threat, the reality is that responding to immediate threats tend to take precedence. This results in more resources being directed toward the most pressing conflicts, giving greater weight to the demands of European Command (EUCOM) and CENTCOM while making it difficult for Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) to attract attention without making particularly drastic statements.

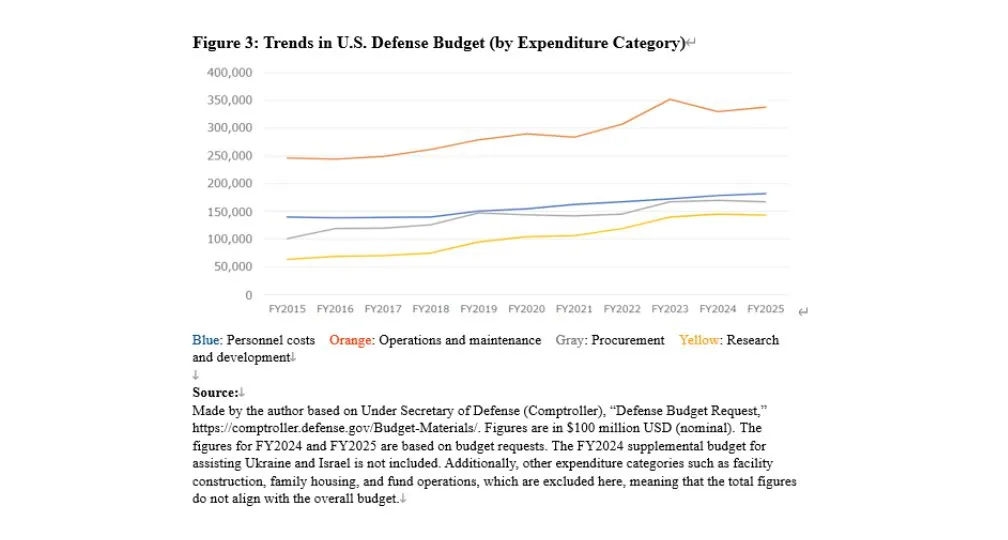

This bias is also reflected in U.S. defense spending, where funding for “readiness” (expenses necessary for operations, training, and maintenance) is prioritized. Ensuring military readiness is, of course, essential for deterrence, but it must always be balanced with long-term investment in future capabilities such as procurement, research and development, and human resource. However, in the 2025 defense budget request summary, the word “readiness” appears 225 times, far outnumbering the mentions of “modernization” (76 times) and “innovation” (37 times). In actual budget allocations, operational and maintenance funding has consistently outpaced procurement and research and development over the past five years (Figure 3).

Even former Marine Corps Commandant David Berger and Air Force Chief of Staff Charles Brown have previously warned against allocating excessive resources to short-term readiness. Because readiness spending is based on the current force structure, it does little to support a dynamic reallocation of resources across the three major theaters. Furthermore, maintaining current equipment—including outdated systems—supports readiness in the short term, which in turn makes it easier for legislators representing districts with defense production facilities to justify policies that protect local defense-related jobs.

Fourth, U.S. allies have collectively contributed to maintaining the status quo. There appears to be an implicit understanding between allies in Europe and the Indo-Pacific on this issue. In essence, a de facto cooperative relationship has formed where European allies seek to maintain the U.S. military presence in their region, while Japan remains reluctant to host politically sensitive assets such as long-range missiles—resulting in a collective acceptance of the current U.S. force posture and scale.

This has led to paradoxical outcomes, such as the U.S. Army’s first overseas deployment of its Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF)—arguably intended to cope with China—being in Germany. While the U.S. and Germany have agreed that this unit will be equipped with long-range missiles by 2026, concerns over public opinion in Japan have reportedly led to the decision to forgo stationing such assets at U.S. bases there. Similarly, the Biden administration’s Global Posture Review (GPR), which largely reaffirmed the existing U.S. global force posture, has been met with low evaluations—partly due to the reluctance of U.S. allies to support major changes.

What Japan Should Do

The U.S. military’s resource dispersion across three fronts is the result of a complex coordination effort among the U.S. military, government officials, Congress, and allied governments. Since much of this stems from domestic factors in the U.S., there is a limited scope for Japan to contribute to a more dynamic shift toward focusing on China. However, there are still a few straightforward measures Japan can take.

First, as one of the U.S.’s most important allies, Japan must accelerate the strengthening of its own defense capabilities. Such efforts would provide objective external legitimacy to the arguments of reformist officers and civilian officials within the U.S. Department of Defense who advocate for prioritizing the Indo-Pacific. This could, in turn, promote similar movements from within the U.S.

Second, Japan should actively accept U.S. proposals for deploying new assets, such as long-range missiles, while carefully examining their specifics. In the Indo-Pacific, there is a harsh reality that disarmament or reduced military burdens does not necessarily lead to peace and stability in the region. Recognizing this reality, proactive collaboration between the Japanese government and local governments hosting U.S. military bases would be essential. Additionally, Japan should support a gradual reduction of U.S. forces in Europe to pre-Ukraine war levels.

Given the U.S. Department of Defense’s large size of bureaucracy, with a combined military and civilian workforce of four million people, it is nearly impossible to achieve optimal decision-making through bottom-up processes alone. In this sense, under current resource constraints, the energy of President Trump—who disdains established bureaucratic decision-making—might be now needed more than ever. It was also during the first Trump administration that the U.S. decisively began its Indo-Pacific shift. Now is the time to reap the fruits of those efforts and boldly prioritize missions. Japan’s role in determining the success of this shift is by no means insignificant.

(Photo Credit: Kyodo News)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Senior Research Fellow

Hirohito Ogi is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) studying military strategy and Japan’s defense policy. Before joining the IOG, Mr. Ogi had been a career government official at the Ministry of Defense (MOD) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) for 16 years. From 2021 to 2022, he served as the Principal Deputy Director for the Strategic Intelligence Analysis Office, the Defense Intelligence Division at the MOD, where he led the MOD’s defense intelligence. From 2019 to 2021, he served as a Deputy Director of the Defense Planning and Programming Division at the MOD. He holds a Master’s degree in international affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), Columbia University, and a Bachelor’s degree in arts and sciences from the University of Tokyo. He is the author of various publications including Comparative Study of Defense Industries: Autonomy, Priority, and Sustainability (co-authored, Institute of Geoeconomics, 2023).

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08