Is there a method behind the Trumponomics madness?

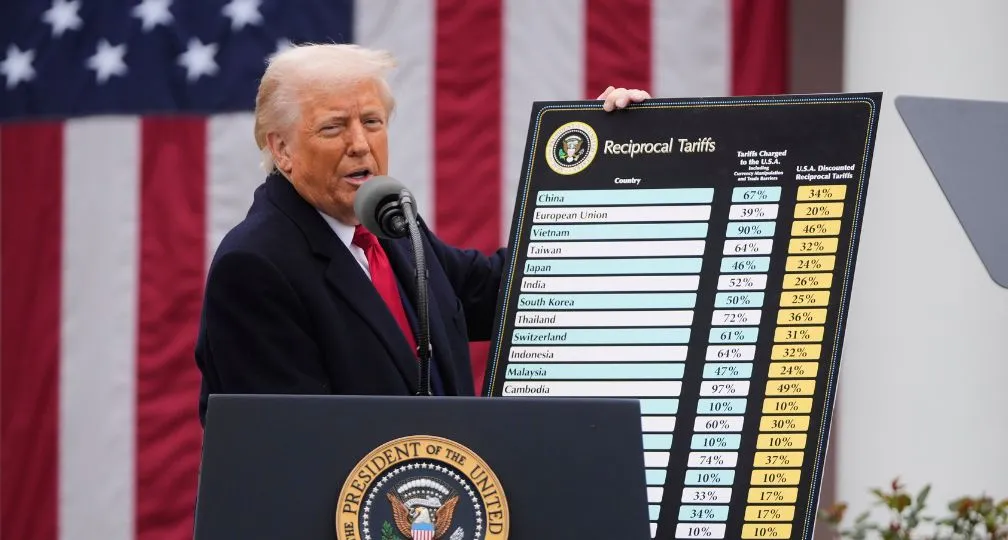

The centerpiece of Trump’s trade policy so far is a sweeping “reciprocal tariff” framework, pitched as a way to punish countries with trade surpluses with the United States. Introduced with fanfare in an April 2 speech, the policy was paused within a week, underscoring a pattern of impulsive policymaking that risks undercutting its own objectives.

Amid this volatility, countries such as Japan are struggling to navigate an economic policy that is, by virtue of the circumstances, more political than strategic — one driven less by long-term goals than by Trump’s desire for quick wins ahead of the 2026 U.S. midterm elections.

What, then, is Washington trying to achieve? And what lies behind the confusion?

Promises first

The administration’s current trajectory strongly reflects its campaign platform, known as “Agenda 47.” With priority areas including the economy, immigration and education, this platform has been driving much of the White House’s actions, for example, actively pursuing campaign pledges regarding transgender issues and the expansion of presidential authority.

Economically, the top priority is Washington’s stance on China. Building on the Trump first-term ban on Huawei and the Clean Network Strategy, the administration is now seeking to eliminate Chinese products from broader supply chains, including energy and pharmaceuticals.

The next top priority is addressing unfair trade practices. This includes reducing trade deficits, eliminating nontariff barriers and countering high tariffs imposed on U.S. exports. The “reciprocal tariffs” policy is central to this effort. The administration has also proposed revoking China’s most-favored-nation status and banning companies with Chinese ties from federal contracts.

In another key priority, the government aims to revive the auto industry by scrapping Biden-era emissions regulations and policies promoting electric vehicles. It also wants to block Chinese-made parts from entering the U.S. via Canada and Mexico.

Tariffs are a key tool in this strategy. Their use — not just against China, but also in sectors like steel and aluminum — doesn’t come as a surprise as Trump employed these tactics in his first term as well. Expanding these measures was another campaign promise that is now being brought to bear.

Promises vs. reality

Pledges made during campaigns often face shifting circumstances and the ability to implement them depends on the political landscape.

In this case, the Trump administration is in a relatively strong position after winning a majority in both the electoral and popular votes and securing slim Republican control of both chambers of Congress. The Supreme Court, bolstered by three Trump appointees, has a 6 to 3 conservative majority. Structurally, few barriers stand in the way of the administration executing its plans.

Yet, rather than building consensus with Congress, the White House is pursuing its aims via executive orders and therefore secure quick wins that can bolster public support for the president. However, such top-down policymaking risks producing initiatives that lack legal coherence, clash with existing agreements and contradict other policy goals.

This centralized method likely reflects lessons from Trump’s first term, when his agenda was frequently obstructed by Cabinet members and legislators. Now, the administration is opting for speed over process.

In economic policy, this haste has produced several complications. Tariffs intended to reduce trade deficits with Canada and Mexico cannot be fully applied due to United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) constraints. Proposed auto tariffs on South Korea, another U.S. free-trade partner, may violate existing deals or will need to be withdrawn, making implementation uncertain.

What is the right response?

The administration appears set to maintain a rapid, top-down policy pace at least until the midterms. The aim seems to be to deliver visible results quickly to avoid becoming a “lame duck.”

Yet many policies seem to be implemented with minimal preparation and are already encountering practical and legal obstacles. For instance, retaliatory tariffs adopted by Canada and contemplated by the European Union have triggered Trump to threaten escalation — putting us more in the realm of a political fight than economic strategy.

That said, actual policy implementation tells a more cautious story. Despite bold rhetoric, the administration has largely excluded USMCA-covered items from new tariff measures. Notably, Trump’s April 2 speech made no mention of revising or withdrawing from USMCA. This suggests that despite appearances, the administration remains constrained by existing legal frameworks unless it takes formal steps to abandon them.

Auto tariffs against South Korea will likewise need to be coordinated with existing trade agreements. And with USMCA being a product of Trump’s first term — replacing NAFTA after a high-profile renegotiation — the administration faces political costs if it moves to dismantle the agreement entirely.

From this perspective, how should Japan respond? While Japan and the U.S. do not share a comprehensive free-trade agreement, they did sign a bilateral trade agreement on goods during Trump’s first term. Like the USMCA, the TAG reflects a mutual understanding — specifically, between Trump and then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. In his April 2 speech, Trump remarked that “Shinzo really understood America’s situation well,” affirming the cooperative spirit behind the agreement.

The TAG was negotiated after the U.S. withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, aiming to maintain some degree of market access. Japan retained tariffs on rice while the U.S. maintained a 2.5% levy on autos and auto parts. Crucially, the agreement includes a clause committing both parties to continue negotiations toward tariff elimination.

Economic Revitalization Minister Ryosei Akazawa, Japan’s top tariff negotiator with the U.S., recently traveled to Washington to secure a deal. However, Japan might be better served by proactively invoking the existing TAG framework. Japan should emphasize that the auto tariff issue — and other trade matters — were already resolved through bilateral agreement and that the U.S. is committed to further talks on eliminating levies.

While TAG as an administrative agreement lacks the binding legal force of a treaty like USMCA, it still carries political weight. In light of the Trump administration’s improvisational style and policy inconsistencies, Japan would be well advised to press for existing commitments to be fulfilled.

(Photo Credit: AP/Aflo)

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on Apri 28, 2025:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2025/04/28/world/making-sense-of-trumponomics/

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Director & Group Head, Economic Security

Kazuto Suzuki is Professor of Science and Technology Policy at the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, Japan. He graduated from the Department of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, and received his Ph.D. from Sussex European Institute, University of Sussex, England. He has worked for the Fondation pour la recherche stratégique in Paris, France as an assistant researcher, as an Associate Professor at the University of Tsukuba from 2000 to 2008, and served as Professor of International Politics at Hokkaido University until 2020. He also spent one year at the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University from 2012 to 2013 as a visiting researcher. He served as an expert in the Panel of Experts for Iranian Sanction Committee under the United Nations Security Council from 2013 to July 2015. He has been the President of the Japan Association of International Security and Trade. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08 Navigating Uncertainty in U.S. Space Policy: Decoding Elon Musk’s Influence2025.04.09

Navigating Uncertainty in U.S. Space Policy: Decoding Elon Musk’s Influence2025.04.09