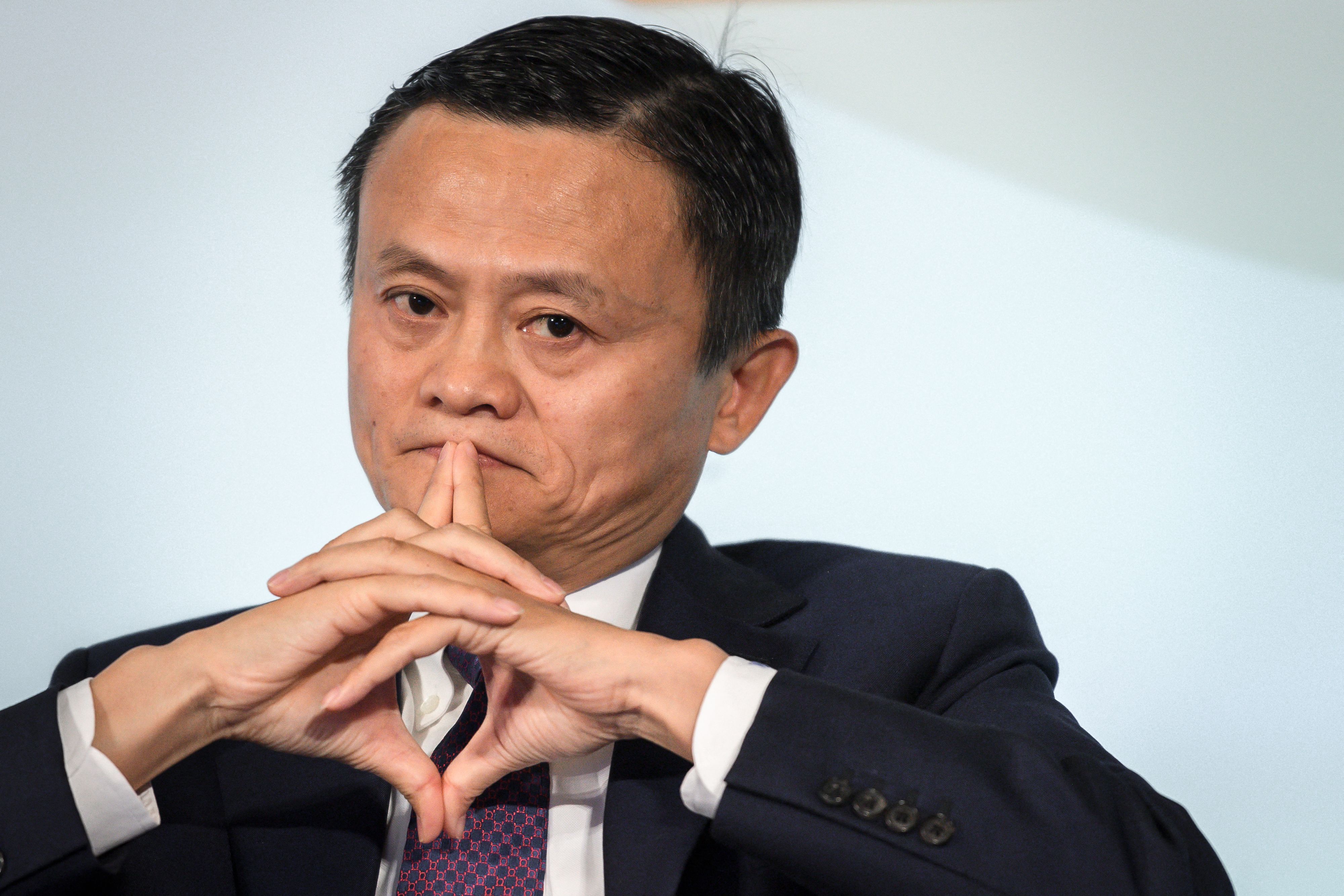

Harnessing China’s tech giants: The case of Jack Ma

Author: Takahiro Tsuchiya, Professor, Kyoto University of Foreign Studies

On Feb. 17, Chinese leader Xi Jinping convened a long-anticipated symposium on private enterprises at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing — the first such gathering in about six years.

Among the notable attendees was Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba Group, whose absence from the public sphere since 2020 had come to symbolize the uncertain status of China’s once-celebrated tech entrepreneurs — until his return at the high-level official gathering.

But Ma’s reappearance wasn’t merely a conciliatory gesture. It marked a broader strategic recalibration. Beijing is now looking to reinvigorate private-sector innovation, global competitiveness and digital infrastructure as part of national policy — treating these not as independent forces, but as levers of state power.

Ma’s return signals the rehabilitation of private entrepreneurs — on the government’s terms — and the symposium earlier this year put forth a renewed model of public-private synergy; one in which private innovation is subordinated to state goals.

This moment also reflects China’s growing ambition to strengthen what political scientists call “meta-power”, the capacity to shape international rules, norms and institutions. Tech giants like Alibaba are being repositioned as geopolitical assets, but Beijing doesn’t view them as independent actors; their influence must be exercised in lockstep with its own interests.

Power in private hands

In the era of globalization and digital transformation, private actors — from corporations to nongovernmental organizations and even individuals — have become increasingly influential vis-a-vis states.

This shift is exemplified by the influence wielded by tech giants based in the United States such as Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft, which control platforms embedded in billions of people’s daily lives. Despite a tightening of antitrust enforcement and rising political scrutiny, their cross-border reach continues to shape global digital norms.

In recent decades, tech firms have started encroaching on spaces traditionally monopolized by the state — regulation, currency systems, information flows — thereby reshaping the geopolitical landscape. In China, Alibaba exemplifies this form of what political economist Susan Strange called “structural power.” Unlike traditional military or economic power, this is exerted in key sectors such as finance, knowledge, technology and markets.

Alibaba e-commerce, digital payments, logistics and cloud computing platforms have become integral to China’s economic architecture: What distinguishes this firm is its deep integration in the structure of modern Chinese life — making it not merely a tech company but an infrastructure provider.

Ma’s rise, fall and now return encapsulates the paradox facing China’s private sector, driven by the ability to innovate and exert influence globally while being constrained by the imperative to conform politically.

Alibaba’s global ambitions

Since its founding in 1999, Alibaba has evolved from a humble e-commerce venture into a sprawling tech conglomerate. Through services like Taobao, Tmall, Alipay and Alibaba Cloud, the company has created an ecosystem that supports countless small businesses and consumer activities all across China.

Furthermore, Alibaba’s reach extends far beyond the country’s borders. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, it has played a key role in fashioning the “Digital Silk Road,” including exporting digital infrastructure — logistics systems, e-commerce platforms and fintech services — to regions such as Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

This effort has not only generated new markets but enhanced China’s soft power. In many developing countries, Alibaba offers virtual services that would otherwise be unavailable. Foreign companies entering China also increasingly rely on Alibaba’s networks, solidifying the firm’s role as a gatekeeper.

All the while, Ma has engaged in so-called corporate diplomacy. By promoting local investment, creating jobs and supporting technology partnerships, Alibaba operates as a quasi-diplomatic actor — at times even fulfilling roles typically reserved for the state.

However, this influence has come with risks. In an authoritarian political context such as China, scale and visibility are a liability. In 2021, Alibaba was fined for antitrust violations and its affiliate Ant Group’s initial public offering — expected to be the world’s largest — was abruptly halted just days before its launch after Ma publicly criticized China’s financial regulators.

Beijing’s message was clear: Private power is tolerated only insofar as it doesn’t challenge the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s supremacy.

Global tech rivalry

China has long adopted a hybrid model, in which private firms contribute to national development but operate within clear political limits. When these companies grow too large or too outspoken, the government doesn’t hesitate to reassert control.

The Ant Group affair was a turning point. The fintech firm aspired to revolutionize finance with data-driven microloans and digital payment systems but regulators balked at its potential of bypassing traditional banking structures — and at Ma’s public criticism of state oversight.

Unlike in countries such as the U.S., where regulatory battles unfold through courts, agencies and legislatures, China’s interventions are swift and opaque. They are also political. Firms are expected to install CCP cells, participate in national development programs and ensure that their leadership echoes party messaging.

These demands create the unique challenge of fostering innovation while maintaining ideological alignment.

On the other hand, the recalibration of public-private relations in China cannot be separated from the intensifying tech rivalry with the U.S. As competition expands into artificial intelligence, semiconductors and information infrastructure, Chinese firms are increasingly seen as strategic actors in a nationwide struggle.

For instance, TikTok, known as Douyin in China, has disrupted social media use globally but has also set off regulatory alarm bells, especially in Western democracies. And Huawei has been sanctioned over concerns that its networks threaten countries’ national security. While technically private, these companies are often seen abroad as extensions of the Chinese state.

A newer entrant, DeepSeek, is gaining traction as China’s answer to ChatGPT. By offering cutting-edge capabilities at lower costs compared to competitors, the AI model exemplifies China’s strategy to outpace Western rivals in frontier technologies. The firm’s emergence has also raised concerns around data governance, security and global artificial intelligence standards.

These cases underscore a fundamental reality: As the boundary between public and private is blurred in the tech sector, companies become proxies in geopolitical contests. In China, this means walking a fine line between government expectations and international scrutiny.

Ma’s return to the public eye may represent a thaw in the CCP’s stance toward private capital — but it also reflects the limits of business influence. Alibaba, once a symbol of unfettered innovation, is now clearly operating within a framework set by the Chinese state.

As Chinese entrepreneurs continue to expand their global footprint, they will likely encounter deeper tensions between their international ambitions and domestic obligations. While American firms contend with lawsuits and congressional hearings, Chinese ones must navigate abrupt interventions and political mandates exercised under the guise of digital sovereignty.

Still, a new model may be taking shape. Rather than stifling private initiative entirely, Beijing is attempting to channel it by embedding entrepreneurs in a system where they contribute not only to economic growth but also to national power.

Whether this model succeeds will depend on how well China balances control with innovation in an increasingly contested global tech landscape.

(Photo Credit: AFP / Aflo)

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on May 26, 2025:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2025/05/26/world/jack-ma-china-tech-entrepreneurs/

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Author

Takahiro Tsuchiya

Professor, Kyoto University of Foreign Studies

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13