Can China Become a Defender of Free Trade?

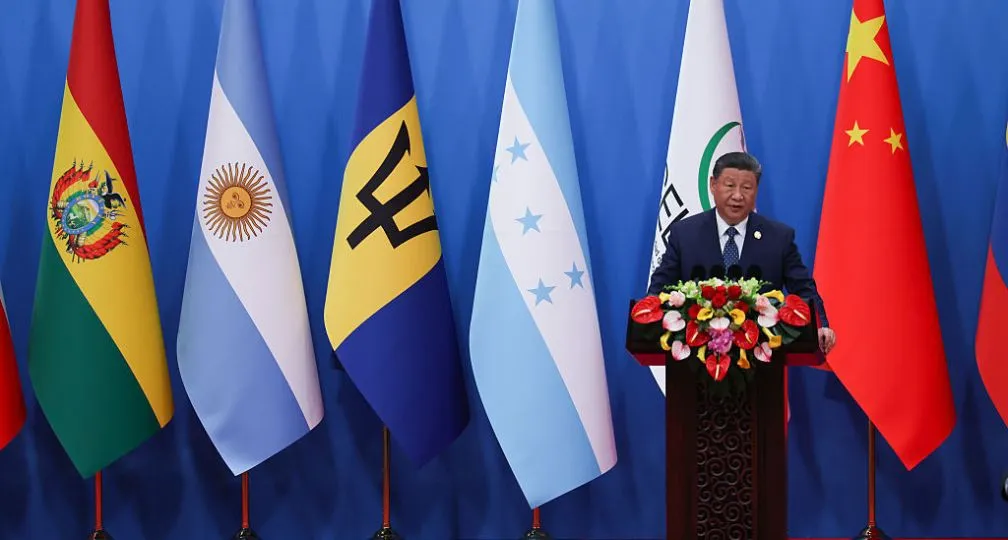

In contrast, China has criticized the “reciprocal” tariffs imposed by the U.S. as protectionist. In response to tariffs exceeding 100% on Chinese goods, Beijing declared it would "see it through to the end," asserting its commitment to preserving free trade and the multilateral trade framework. Similarly, when the U.S. announced its departure from the Paris Agreement, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned the move, stating that climate change is a shared challenge for all humanity and that unilateral actions by individual nations are unacceptable.

In short, China has begun to present itself as a defender of free trade and multilateralism. But can China truly become a protector of the international order? And how should we engage with a China that now claims to champion free trade?

The Kindleberger Trap?

In January 2017, American political scientist Joseph Nye warned of two traps involving China’s rise. A China that becomes too strong, he said, could lead to war with the U.S.—a classic “Thucydides Trap.” But a China that remains too weak may also be dangerous: without a strong power to provide global public goods, the international order may unravel—this is the “Kindleberger Trap.” Nye noted that global public goods like financial stability and freedom of navigation are supplied by great powers, and if China continues to free-ride, the provision of these goods could collapse, destabilizing the world.

Since then, China has seemingly committed itself more in international organizations like the UN and launched its global initiatives on development, security, and civilization. It claims programs like the Belt and Road Initiative, the AIIB, and its “Community with a Shared Future for Mankind” contribute to global public goods.

Yet many argue that China benefits from global public goods without sharing the cost. Its rise has relied heavily on free trade and multilateralism, but it has been reluctant to address negative spillovers—like overproduction harming foreign industries. It has also used its vast domestic market to pressure foreign firms for technology transfers, reflecting a “China First” attitude beneath the rhetoric of free trade.

China has also taken advantage of multilateral systems, such as its permanent seat on the UN Security Council and the one-country-one-vote structure. Since 2018, China has submitted numerous resolutions to international organizations, embedding its favored concepts while deflecting criticism over human rights abuses in places like Xinjiang and Tibet.

The Xi administration views the West’s declining influence and the rise of the Global South as a strategic opportunity to reshape global governance. But although China shows a willingness to offer public goods, its capacity remains limited.

For instance, in 2022, it announced the Global Security Initiative, attracting support from developing nations. Still, amid crises such as the Ukraine war and the Israel-Hamas conflict, China has offered little more than statements. And in response to Trump’s tariffs, China insisted on defending multilateral trade but only matched U.S. actions with retaliatory tariffs. It has neither opened its own markets meaningfully nor proposed a new trade framework to replace the one the U.S. is retreating from.

A U.S. Retreat from the Existing Order, and a China Pushing Back

The U.S. was the leader of the postwar international order, but while it retains the ability to provide public goods its political will appears to be weakening. With authoritarian states weaponizing economic ties and dual-use technologies expanding, economic activity is increasingly tied to national security. This shift has fueled calls in the U.S. for economic restrictions justified by security concerns.

From the U.S. perspective, China is not only willing but also capable of reshaping the international order to suit its interests. The U.S. is wary of initiatives like the Belt and Road and the “Community with a Shared Future for Mankind,” which it sees as attempts by China to revise global norms. Washington is increasingly intolerant of what it considers China’s exploitation of free trade and multilateralism.

Despite its ambitions, China faces immense domestic challenges and remains focused on economic growth and technological self-sufficiency. It is not in a position to sacrifice its own interests for the global good, nor has it offered concrete alternatives to the current rules-based system. Still, China is attempting to position itself as a defender of free trade and multilateralism, especially as the U.S. appears to be pulling back.

During Xi Jinping’s May visit to Russia, the two nations issued a joint statement on upholding international law and global stability. Two countries are trying to benefit from the existing system while offering little in return—exemplifying another form of strategic free-riding.

How Should We Engage with China?

Since World War II, the U.S. has borne the burden of providing global public goods, such as supporting free trade and multilateral institutions. These systems don’t sustain themselves just because countries claim to support them. If China wants to be seen as a true defender of the international order, it must stop using it solely for its own gain and take concrete actions for its upkeep.

For example, if China is serious about free trade, it should address overproduction not pretending the issue doesn’t exist, and refrain from using its market size to extract concessions from trading partners. It should also take meaningful steps—like improving transparency in government procurement and reforming state-owned enterprises—if it is sincere about joining high-standard agreements like the CPTPP.

If China truly values multilateralism, it must accept the rulings of international organizations, even when they are unfavorable, and stop coercive behavior in contested areas like the South China Sea. It must also respond seriously to human rights criticism and not simply dismiss it as interference.

Japan, with limited natural resources and a strategic location surrounded by military powers, relies on the global rule of law, free trade, and multilateralism. As the U.S. grows increasingly frustrated and leans toward unilateralism, Japan must try to address U.S. concerns while helping to maintain international frameworks.

If China fails to step up and the U.S. steps back, the world risks falling into the Kindleberger Trap—where no country is willing or able to support the system, and global stability collapses.

Professor Nye, in his earlier writings, warned the Trump administration not to misjudge or miscalculate China’s actual capabilities. While Beijing often speaks with confidence, its actions often doesn’t match its rhetoric. Japan, along with European allies, must continue pressing both the U.S. and China to act responsibly and support a stable and prosperous international order.

(Photo Credit: AFP / Aflo)

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

MACHIDA Hotaka is a visiting senior research fellow in Institute of Geoeconomics at International House of Japan. He joined the Institute in October, 2022. Prior to leaving his role in government, he served as a career diplomat in Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2001 to 2022, focusing on Japan-China relations. He studied at Nanjing University in China and Harvard University in the United States, followed by working at Embassy of Japan in China as second secretary from 2006-2008. After that, he was posted in China-Mongolia division in the Ministry and completed the negotiations with China over the issues of launching the “High-Level Consultation on Maritime Affairs” as well as finalizing the “Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR)” agreement. He also worked in Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) division in the North America Bureau in the Ministry leading the negotiations with the US on SOFA-related issues. He was counsellor in the Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations (2017-2020) and Embassy of Japan in China (2020-2022) covering the Security Council reform and Japan-China economic relations respectively. He holds a M.A from the Graduate School of Arts and Science at Harvard University, and a Bachelor from Law Faculty at Tokyo University.

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13