In chip renaissance, Japan is learning from past mistakes

Japan is in the midst of a semiconductor renaissance.

Japan Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing (JASM) — a joint venture between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), Sony, Denso and Toyota — kicked off production at its first fab plant at the end of last year and has already announced plans to build a second factory. Both facilities are located in Kumamoto, fast emerging as Japan’s semiconductor hub.

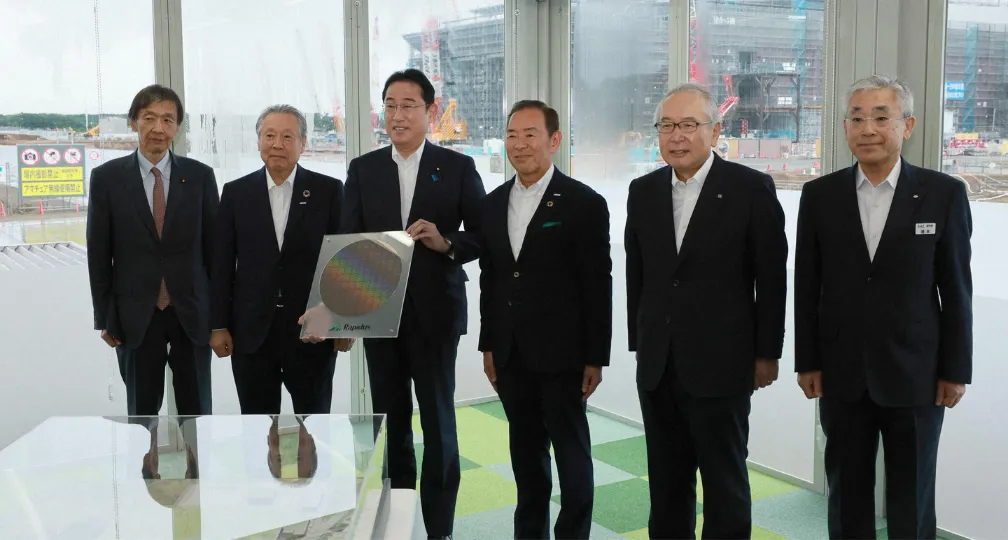

In a significant leap forward, Rapidus — a foundry aiming to produce 2-nanometer semiconductors — was launched in collaboration with the American IBM and Belgium’s Interuniversity Microelectronics Center (Imec), with a new facility under construction in Hokkaido.

In addition, TSMC has partnered with the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology to establish a research center focused on advanced 3D chip stacking and Samsung has created its own cutting-edge facility in Yokohama.

While this is not the first time that Japan attempts to lead in semiconductor technology, it can benefit from lessons learned from past missteps. And while it remains to be seen if the current government is as committed to propelling this sector as its predecessors, if Japan emerges as a central player in the global chip industry, the geoeconomic ripple effects will be felt not just in Tokyo but in capitals across the world.

Yesterday’s failure

In the 1980s, Japanese firms accounted for half of the global semiconductor market. Today, that figure has fallen to below 10%. While Japan still maintains international competitiveness in manufacturing equipment and materials, its share in finished chips has dropped drastically.

Some argue that the 1986 U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Agreement, which restricted Japan’s access to the American market, played a significant role in the domestic chip industry’s decline. In truth, this was only one factor among many and their combined effect explains the downward trend — and structural issues played a bigger role, in any case.

For starters, Japan’s insistence on the integrated device manufacturer (IDM) model was counterproductive. Many of its semiconductor companies, such as Hitachi and Toshiba, were part of large electronics conglomerates whose semiconductor divisions handled everything from design to manufacturing and packaging. But to stay competitive in this industry, heavy and sustained capital investments are essential — challenging to devote to a single division, even in a large corporation.

In contrast, TSMC pioneered the foundry business model, specializing solely in chip manufacturing. This allowed other companies to focus on high-value areas like development and design, while TSMC concentrated on high-precision production in substantial volumes for multiple clients. This led to better yields and more profitability, which TSMC reinvested into further capital expansion.

As the semiconductor industry moved toward international specialization, Japan’s adherence to IDM left it unable to compete with capital- and technology-rich foundries like TSMC.

Japan also struggled with industrial restructuring. Semiconductor production assets and talent were spread across multiple companies, hindering their ability to scale production effectively in a sector that demands it.

The government attempted an “all-Japan” approach to consolidate resources, aiming to unify talent and production. However, companies were reluctant to share key personnel and proprietary knowledge, and these projects ultimately fell short. Meanwhile, TSMC’s consolidated model quickly propelled it to global leader status, while Japanese firms remained bogged down by domestic competition.

Ironically, consolidation did eventually occur in Japan with the formation of companies like Renesas Electronics, but by then it was too late.

Today’s strategy

Building on past lessons, Japan has relaunched its semiconductor strategy as part of its economic security policy, prioritizing strategic autonomy.

In recent years, incidents such as a winter storm in Texas and a fire at Renesas’ Hitachinaka plant in Ibaraki Prefecture have led to serious chip shortages, impacting not only the automotive industry, but the supply of products ranging from water heaters to IC cards.

The government has thus moved to secure domestic semiconductor production by supporting not only homegrown players, but attracting foreign ones: In the case of TSMC, it agreed to cover around half of factory construction costs. This should ensure a steady supply of the 28-nanometer semiconductors that are in high demand in automotive electronics and camera image sensors. The all-Japan approach has thus shifted to boosting any firm — regardless of nationality — that establishes its production in Japan.

The government has also supported the creation of Rapidus with the goal of securing strategic indispensability. Demand for artificial intelligence semiconductors is expected to surge, but only a few companies, such as TSMC, can produce the graphics processing units needed for such applications, resulting in a global shortage. If Rapidus succeeds in producing 2-nanometer chips, Japan will become an essential player in the global market.

Crucially, the country’s expertise is currently limited to 40-nanometer semiconductors. To overcome this, Rapidus is collaborating with IBM for personnel training and with Imec for research in 2-nanometer technology.

By embracing international collaboration, Japan has moved on from its past commitment to IDM, acknowledging the importance of contributing to global supply chains.

Tomorrow’s challenges

For Japan to succeed, it must overcome several hurdles. One is funding. The government has allocated ¥1.2 trillion ($7.7 billion) in subsidies to JASM’s Kumamoto plants and an additional ¥920 billion to Rapidus. While JASM is propped up by contributions from TSMC, Sony and Denso, who handle their own fundraising, Rapidus only has eight investors, with total contributions amounting to ¥7.3 billion — a fraction of the subsidies it receives.

In September, it was reported that three major Japanese banks and the Development Bank of Japan plan to invest a combined ¥25 billion in Rapidus. Nevertheless, this may fall short of ensuring the venture’s long-term viability. Given the industry’s capital-intensive nature, constant investments are essential to maintain cutting-edge production and remain internationally competitive. Without a sustainable funding cycle, Japan risks reliving past failures.

Although revenue from mass production could be funneled into future investments, securing enough financing to reach this stage remains a significant hurdle. Under the previous government, a bill was drafted to provide government guarantees for Rapidus investments, but with October’s general election, this effort was temporarily halted. Passing this bill and attracting private investment are much-needed steps forward.

Another major challenge is securing talent. While core staff have received training through programs like the one with IBM, semiconductors require a broad supply of skilled workers, including from various suppliers. Rapidus has already partnered with Hokkaido University for this purpose, but it is uncertain whether enough talent can be trained before mass production begins.

This shortage of human resources is not unique to Japan, with similar issues emerging in Taiwan and the United States, signaling a global dearth in skilled labor. International competition for talent will therefore be crucial.

If Japan can overcome these challenges, it can establish itself as a semiconductor production hub, achieving both strategic autonomy and indispensability. To secure the necessary funds and workforce, continued government support will be essential.

(Photo Credit: Mainichi Newspapers/ Aflo)

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on March 3, 2024:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2025/03/03/japan/japan-semiconductor-renaissance-past/

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Director & Group Head, Economic Security

Kazuto Suzuki is Professor of Science and Technology Policy at the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, Japan. He graduated from the Department of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, and received his Ph.D. from Sussex European Institute, University of Sussex, England. He has worked for the Fondation pour la recherche stratégique in Paris, France as an assistant researcher, as an Associate Professor at the University of Tsukuba from 2000 to 2008, and served as Professor of International Politics at Hokkaido University until 2020. He also spent one year at the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University from 2012 to 2013 as a visiting researcher. He served as an expert in the Panel of Experts for Iranian Sanction Committee under the United Nations Security Council from 2013 to July 2015. He has been the President of the Japan Association of International Security and Trade. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo

View Profile-

Japan’s Sea Lanes and U.S. LNG: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.02.24

Japan’s Sea Lanes and U.S. LNG: Towards Diversification and Stabilization of the Maritime Transportation Routes2026.02.24 -

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09