The Fissures Beneath China’s Positive GDP Numbers

Difficulties of Economic Recovery

As the U.S.-China trade conflict grinds on, Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng continues to signal that Beijing is “confident” in the strength and trajectory of its economy.

In support of that optimism, economic growth exceeded Beijing’s full-year target in the second quarter, with gross domestic product expanding 5.2% in April to June from the previous year.

But despite positive growth — largely due to increased exports outside the U.S. market — the world’s second largest economy is plagued by a prolonged real-estate crisis and persistently high unemployment rates. Beijing is aiming for economic revitalization by expanding domestic demand and enhancing production capabilities. But structural issues — including population decline, job shortages and an insufficient social-safety net — are hampering consumption and demand.

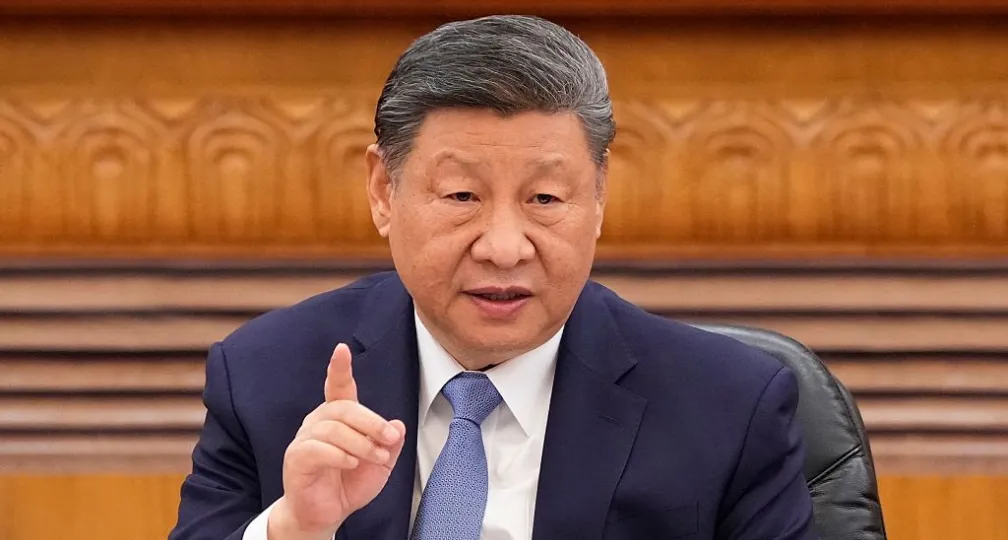

Beijing has acknowledged the difficulties of economic recovery while claiming that the situation is gradually improving. On April 25, at a meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee chaired by President Xi Jinping, the Xi administration noted “signs of economic improvement” and set forth a policy to strengthen macroeconomic measures, including proactive fiscal policies and accommodative monetary policies.

But that’s not exactly a rosy forecast. China’s communist leaders have long used optimistic messaging in times of turmoil to influence both domestic and international opinion — maintaining the supremacy of what they call “positive energy” and reinforcing the Communist Party’s cohesion. In other words, China may be projecting optimism precisely because it fears a negative spiral resulting from the U.S.-China conflict.

On the other hand, it is also possible that the party leadership operates from a different perspective, one rooted in a more long-term strategy. In other words, Beijing’s “confidence” may not be based on short-term victories in its recent tariff battles with Washington but on its self-assessment that it holds a relatively advantageous position in mid-to-long-term competition with the U.S.

Indeed, the Trump administration’s tariffs are merely the opening salvo of a broader strategic competition. The U.S.-China rivalry spans multiple domains, including politics, economy, security, values and technology — a complex game with many layers. Judging the success or failure of the tariff war based solely on current trade dependency and other factors only captures a fragment of the picture.

China’s latent advantages lie in its vast domestic economy. The first is economies of scale in manufacturing and abundant human resources. Because China has a sufficiently large market within its own borders, it can develop domestic markets for new products relatively easily. Although policy measures sometimes lead to side-effects like overproduction, China swiftly produces competitive companies in emerging industries.

Consequently, companies that survive domestic competition become stronger. The second advantage is China’s extensive involvement in global supply chains. Although relative production costs have increased, many industries still cannot envision global supply chains without China.

Based on these inherent strengths, the Chinese government has been advancing policies such as the “Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy” and “Made in China 2025,” which aim to make the country a manufacturing superpower through government and private-sector partnerships. In addition, China plans to further involve the private sector to promote the social implementation of technology in designated “future industries,” such as generative AI, robotics, quantum computing and health care, creating new markets and potentially reshaping society. This is likely the basis for the Xi administration’s apparent confidence.

Japan’s Strategy

So, how should Japan engage with China? As Donald Trump’s America retreats from its role as the leader of the liberal order, international dynamics have become increasingly fluid. Political opacity in China continues and it remains unclear how long its policy of favoring private and foreign enterprises will persist. Conversely, if China advances toward becoming a manufacturing superpower, economic ties between Japan and China in certain sectors may deepen.

One of the big risks to consider in this scenario is the potential for military action over Taiwan. Security analysts have consistently suggested the possibility of military action in 2027, coinciding with Xi’s potential fourth term. This theory first gained attention when the since retired Adm. Philip Davidson, then commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, mentioned it during a congressional hearing in March 2021. In February 2023, then-CIA Director William Burns also stated that intelligence indicated Xi had ordered the PLA to gain capability for a successful invasion of Taiwan by 2027. And in March 2025, Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense officially identified 2027 as a possible year for Chinese aggression.

At the same time, many China specialists argue that military action is not realistic due to its excessive cost. My view is that the likelihood of military conflict in East Asia within the next two years is very low for three reasons. First, at least for the time being, prioritizing the domestic economic recovery will take precedence. Second, there are governance challenges that would arise post-annexation, including immense governance costs. Third, a failed military action would risk destabilizing China’s one-party dictatorship, leading to a loss of legitimacy. These considerations make military action a less rational choice.

To maintain a stable Japan-China relationship, it is crucial for Tokyo to reassess the benefits and risks associated with Beijing from a comprehensive perspective. Deepening cooperation with China in technology development may bring economic and social benefits, but in the long run, Japan might face a stronger China, ironically heightening its own risk with the Asian giant.

To manage the complex interplay of economic and security-related China risks, Japan must urgently establish and share a vision of economic security across both the public and private sectors and deliberate a strategic approach moving forward.

(Photo Credit: Pool / Getty Images)

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this IOG Commentary do not necessarily reflect those of the API, the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

API/IOG English Newsletter

Edited by Paul Nadeau, the newsletter will monthly keep up to date on geoeconomic agenda, IOG Intelligence report, geoeconomics briefings, IOG geoeconomic insights, new publications, events, research activities, media coverage, and more.

Visiting Senior Fellow

Naoko Eto is a professor in the Department of Political Science at Gakushuin University. Her main research interests include East Asian affairs and Japan-China relations. She is a member of the Expert Committee on Industrial and Technological Infrastructure Strengthening for Economic Security at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Industrial Structure Council, METI and the Customs and Foreign Exchange Council at the Ministry of Finance (MOF). She was also a visiting research fellow at the School of International Studies, Peking University, the East Asian Institute, Singapore National University, and a visiting senior fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Department of Political Science, Gakushuin University

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 -

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Trump, Takaichi and Japan’s Strategic Crossroads2026.02.03

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13