How AI fits into China’s raft of global initiatives

The presence of Elon Musk, who launched his artificial intelligence startup xAI, drew much attention. The company released a new generative AI chatbot called Grok soon after the summit.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who joined the conference virtually, referred to the Group of Seven joint statement of Oct. 30 about the “Hiroshima AI Process” — an initiative on AI-related rule-making agreed upon at the G7 Hiroshima summit in May — and announced a plan of developing the Hiroshima AI Process Comprehensive Policy Framework and its work plan by the end of this year.

Prior to that, the European Parliament adopted its negotiating position on the AI Act on June 14, which is set to take effect in 2024. And, on July 10, the Chinese government promulgated the Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services, which came into effect on Aug. 15.

U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration issued its Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence on Oct. 30 to introduce legally binding regulations, develop guidelines for new safety evaluation standards and advance equity and civil rights.

Behind global moves to consider AI-related regulations lies a serious sense of crisis among those who believe an urgent discussion is needed about the fact that AI offers not only new opportunities for society but also risks.

And as the use of AI in the military field has become a focus of U.S.-China confrontation, the moves indicate countries’ intention to lead rule-making efforts on AI, which will become a game changer in the economy, military and security arenas.

AI governance in China

Turning to China, the development of AI in the country has progressed swiftly since the 2010s.

Related policies were expanded at a rapid pace after its 13th five-year plan (2016-20) for the development of strategic emerging industries, adopted in March 2016, specified AI as key to achieving economic growth targets.

In July 2017, Beijing issued a new-generation AI development plan that presented strategic objectives for 2020 and 2025 to make China’s AI theories, technologies and applications reach world-leading levels by 2030.

And after the city of Beijing was designated in 2019 as a New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development National Experimental Zone — the first of its kind in China — various measures were taken on local government levels, mainly in Beijing, Guangdong province, Zhejiang province and Shanghai, contributing to the social implementation of the technology.

At the same time as promoting AI, the Chinese government has also been regulating it. For instance, the Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services states as follows in Chapter I Article 4 (1):

“Uphold the Core Socialist Values; content that is prohibited by laws and administrative regulations such as that inciting subversion of national sovereignty or the overturn of the socialist system, endangering national security and interests or harming the nation’s image, inciting separatism or undermining national unity and social stability, advocating terrorism or extremism, promoting ethnic hatred and ethnic discrimination, violence and obscenity, as well as fake and harmful information.”

The provision is similar to what is stated in Article 12 of China’s Cybersecurity Law in terms of deterring political system crisis and social turmoil, but the phrase “uphold the core socialist values” could be used as the basis to control public opinion related to ideology.

Ahead of the AI Safety Summit held in November, some voices opposing China’s participation were heard in the United Kingdom. Former Prime Minister Liz Truss also demanded that the U.K. reconsider inviting China to the summit, saying Beijing sees AI as a “means of state control and a tool for national security.”

Prior to the summit, Harris, in a speech at the U.S. Embassy in London, said biased AI facial recognition and AI-enabled misinformation and disinformation are threats to democracy, in a veiled reference to China.

Still, U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s administration chose to invite China, an AI superpower, and Chinese Vice Minister of Science and Technology Wu Zhaohui was present at the summit.

China also agreed to the Bletchley Declaration. This statement, signed at the summit, said that the participating countries resolved to sustain and broaden international cooperation.

Chinese media reported on the declaration quoting experts saying a future model to address AI-related risks was being formed with the participation of China, a country too big to ignore when it comes to global AI cooperation.

Global AI Governance Initiative

Why did China decide to keep pace with the U.K.-led cooperation framework?

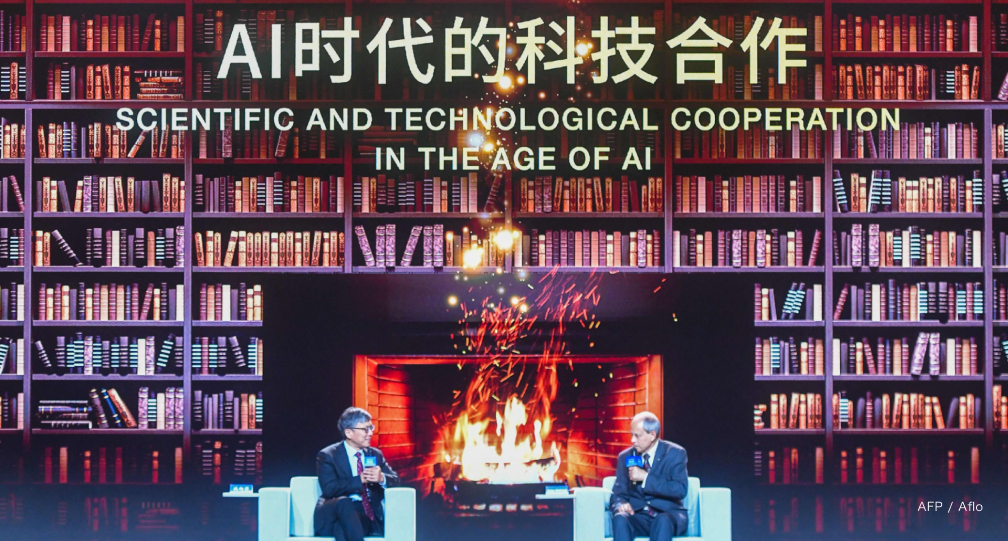

In forecasting China’s future diplomatic strategy, it is imperative to look into the Global AI Governance Initiative (GAI) presented at the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation held in Beijing in October.

The administration of Chinese President Xi Jinping has been showing its intention to get involved in global governance through three initiatives: the Global Development Initiative (GDI) released in 2021, the Global Security Initiative (GSI) released in 2022 and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) released in March.

In addition, Beijing launched the GAI at the opening of the Belt and Road forum. But what does this imply?

The Xi administration’s global vision has been aimed at realizing a concept of a “community with a shared future for mankind” based on the three diplomatic strategy initiatives, with China leading efforts to achieve the goal.

“Community with a shared future for mankind” is a phrase that calls for the building of a bright future for everyone — an “open, inclusive, clean and beautiful world that enjoys lasting peace, universal security and common prosperity” — and China under Xi’s leadership is pushing forth an image that the country is striving to realize such a world.

In other words, the three initiatives represent China’s strategy of attempting to change the international order by exerting power in the domains of economy, military and values.

Specific measures for such an attempt are taken under another Chinese measure, the Belt and Road initiative (BRI).

This year, the 10th anniversary of the launch of the BRI, the Chinese government tried to overturn criticism over sloppy project management and accusations that the initiative is a “debt trap” for developing countries by promoting small-scale plans to give the impression that the BRI projects have gone through qualitative change.

Such an intention was apparently behind the Belt and Road forum held on Oct. 17 and 18 under the theme “High-quality Belt and Road Cooperation: Together for Common Development and Prosperity.”

Prior to the forum, on Oct. 10, the Chinese government released a white paper titled “The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future” to present the achievements of the BRI during the past decade, while also stressing the importance of refurbishing it.

Based on such understanding, the announcement of the GAI can be seen as China hoping it will serve a double purpose; gaining power in the fourth domain of science and technology, and promoting a national image as an earnest supporter of the development of the international economy.

It is noteworthy that all the initiatives — the GDI, GSI, GCI and GAI — were announced by Xi himself at international conferences. In September 2020, then-Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi unveiled the Global Data Security Initiative, but this plan was little mentioned after that and is ranked below the GDI, GSI and GCI.

Preferable cooperation with China

The GAI document announced by Beijing is short and lacks depth. Yet the fact that the document was released in English as well as Mandarin indicates that Beijing wanted to send out a message quickly to the international community.

The document points out at the start that there are both opportunities and risks regarding the development of AI, saying it has “exerted profound influence on socioeconomic development and the progress of human civilization, and brought huge opportunities to the world.” However, it may also “bring about unpredictable risks and complicated challenges.”

“Countries should build consensus through dialogue and cooperation, and develop open, fair and efficient governing mechanisms,” the document states.

It goes on to say: “We should respect other countries’ national sovereignty and strictly abide by their laws when providing them with AI products and services.”

The document also states: “We oppose using AI technologies for the purposes of manipulating public opinion, spreading disinformation, intervening in other countries’ internal affairs, social systems and social order, as well as jeopardizing the sovereignty of other states.”

This indicates Beijing’s view that such actions could be seen as interference in other countries’ internal affairs. In the concluding paragraph, it says: “We should increase the representation and voice of developing countries in global AI governance.” It is clear that China made the proposal from the standpoint of developing countries.

The Xi administration attaches great importance to AI technology and is actively set on promoting it within the country while working on international rule-making.

And it should be noted that Beijing chose the Belt and Road forum as an opportunity to announce the GAI and presented it from the perspective of developing countries, which are weak in terms of technology.

Such a move implies that while China is a country with cutting-edge technologies, it sees benefits in drawing a line between itself and other industrialized nations and is trying to put itself in a favorable position in the international community by maintaining the position of a developing country.

In other words, Beijing is differentiating itself from Western countries, which is a strategy also seen in the competition over international discourse power, as discussed in a previous article in this series.

The Xi administration probably thinks that the process of AI-related rule-making itself is a competition. Beijing is likely to maintain domestic AI regulations with the rationale of preventing other countries’ intervention in internal affairs, and it will also work on winning the support of developing countries.

On the other hand, other countries need to get China involved in an international framework. It might be possible to share rules, such as requiring watermarking to help identify AI-generated images and deepfake speech.

The U.S. and China have already agreed to an intergovernmental dialogue on AI at their Nov. 15 summit meeting, and further progress is expected.

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on December 7, 2023:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2023/12/07/world/china-global-initiatives/

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the International House of Japan, Asia Pacific Initiative (API), the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

Visiting Senior Fellow

Naoko Eto is a professor in the Department of Political Science at Gakushuin University. Her main research interests include East Asian affairs and Japan-China relations. She is a member of the Expert Committee on Industrial and Technological Infrastructure Strengthening for Economic Security at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Industrial Structure Council, METI and the Customs and Foreign Exchange Council at the Ministry of Finance (MOF). She was also a visiting research fellow at the School of International Studies, Peking University, the East Asian Institute, Singapore National University, and a visiting senior fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Department of Political Science, Gakushuin University

View Profile-

Attack on Iran: What Comes Next for the Gulf & The Oil Crisis?2026.03.02

Attack on Iran: What Comes Next for the Gulf & The Oil Crisis?2026.03.02 -

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27 -

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08

A Looming Crisis in U.S. Science and Technology: The Case of NASA’s Science Budget2025.10.08