Xi’s Balancing Act: Competition Abroad, Discipline at Home

It proved an effective strategy. During the U.S.-China talks on Oct. 25 and 26, the two sides reached a deal: China would postpone enforcement of the export restrictions for one year, while the United States also postponed its threat to apply 100% tariffs on Chinese imports.

Two days later, Chinese Premier Li Qiang signed a revised free-trade agreement with the Association of Southeast Asia Nations, asserting that expanding trade is a “legitimate right.” These actions illustrate Beijing’s steady pursuit of a familiar strategy — emphasizing multilateralism to contrast itself with U.S. unilateralism while consolidating a regional sphere of influence.

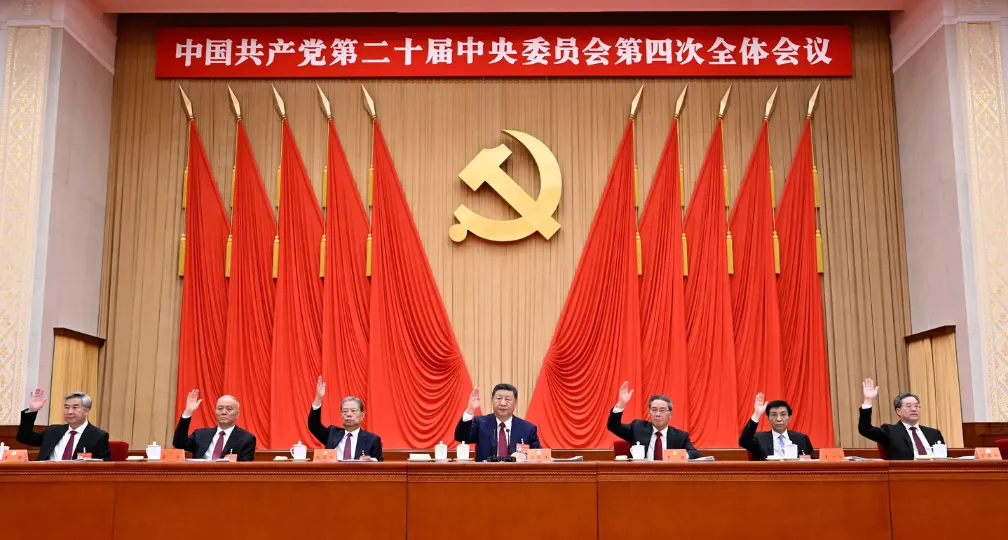

Yet China’s external assertiveness masks deep domestic uncertainty. At the Fourth Plenum of the 20th Central Committee (Oct. 20 to 23), the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reviewed the 15th Five-Year Plan, reaffirmed national goals through 2035 and urged the nation to “unite more closely around the Party center with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core.”

Despite continued U.S. tariff pressure, China has offset much of the impact by redirecting exports to other markets — a continuation of the “confident posture” analyzed in a recent Geoeconomic Briefing, published in early September.

Still, a transition toward a demand-driven economy remains elusive. The prolonged real-estate slump and growing fears of “deflationary exports” from Chinese firms — flooding Asia and Global South countries with cheap goods — underscore the fragility of China’s growth model. As Chinese leader Xi mixes hard and soft diplomacy abroad, domestic control has tightened, raising the question of how China’s foreign activism connects to its deepening internal constraints.

Anxiety and propaganda

In March 2025, Beijing set its growth target at around 5% and prioritized “comprehensive expansion of domestic demand.” Yet the National Bureau of Statistics reported that third-quarter gross domestic product grew only 4.8% year-on-year (down from 5.2% in the second quarter), while nominal growth slowed to 3.7% (3.9 % in the second quarter). The causes for this are structural: a shrinking population, weak social safety nets, a stagnant property market and persistent income inequality.

Despite these headwinds, official messaging remains overwhelmingly positive. During the October National Day holidays, per capita consumption fell 0.6% from a year earlier, yet Xinhua reported that 888 million domestic travelers spent 809 billion Chinese yuan, portraying the outcome as proof that stimulus policies had “unlocked new experiential consumption.”

The tone reflects the CCP’s continuous directive since the December 2023 Central Economic Work Conference to “strengthen economic publicity and opinion guidance, and advocate the bright prospects of China’s economy.” Around the same time, the Ministry of State Security warned against “defamation” of the Chinese economy, hinting at penalties. The aim includes to restore confidence amid faltering demand, yet this “bright-outlook theory” risks distorting perceptions and concealing vulnerabilities.

The narrative also serves a broader ideological purpose. By promoting the success story of “Chinese-style modernization,” Xi seeks to portray China’s authoritarian model as a legitimate alternative to liberal democracy. Economic optimism thus underpins an argument for regime endurance — reinforcing political control under the guise of confidence.

Politics of narrative

Xi’s international vision of a “community with a shared future for mankind” rests on four conceptual pillars: the Global Development, Global Security, Global Civilization and Global Governance Initiatives. The newest, the Global Governance Initiative (GGI), unveiled at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Plus Summit in September, marks an effort to project China as a co-leader of global rule-making alongside the United States.

Unlike its predecessors, which targeted the economic, security and value domains, the GGI focuses on institutional leadership itself. Announced just before the 80th anniversary commemorations of the end of World War II, the initiative sought to invoke China’s status as a wartime victor and to legitimize its aspiration to reshape the postwar order.

Why this proliferation of narratives? Fundamentally, China’s external messaging mirrors its domestic propaganda system. Yet its influence abroad remains limited: Beijing lacks the coercive tools to make others adopt its worldview. Consequently, success is measured less by policy impact than by visible acceptance of Chinese rhetoric. If many countries publicly echo Chinese concepts, Beijing interprets that as proof of rising “leadership” and thus expanding influence.

In this sense, the promotion of the GGI is less about substance than signaling. It functions as a gauge of propaganda power — an indicator that China’s voice is being heard, even if not fully believed. The more governments and institutions refer to Chinese-framed concepts, the more Beijing can claim legitimacy for its model of governance and diplomacy.

Tightening control

As the 2027 Chinese Communist Party 21st National Congress approaches, political and ideological control are again intensifying. The pattern dates back to 2022 when speculation that Xi might assume the revived title of “party chairman” proved unfounded and language codifying the “Two Establishments” of his authority was omitted from the final Party charter — signaling internal opposition.

In response, disciplinary measures have hardened. In May 2025, the CCP revised its procedures for reviewing and deciding disciplinary actions against Party members, followed in August by new rules for the Central Party School (National Academy of Governance). On Sept. 16, the Central Committee circulated the regulation on the CCP’s ideological and political work, a flagship project under the Outline Plan for Intra-Party Regulations (2023–2027).

Though not published online, the regulation reportedly extends “thought work” across multiple arenas — beginning with enterprises, followed by rural collectives, state agencies, schools, communities, emerging industries and cyberspace. The prioritization of ideological oversight within the private sector is particularly striking. By embedding CCP doctrine inside corporate management, Xi is seeking not only loyalty, but structural fusion between the Communist Party and China’s productive economy.

The cumulative effect is growing rigidity. Expanded ideological control restricts open debate and research freedom — core drivers of innovation. Xi appears to recognize that suppressing intellectual diversity undermines long-term competitiveness, yet his strategy continues to prioritize cohesion over creativity. The contradiction is stark: Efforts to consolidate power through conformity may ultimately weaken China’s ability to compete in technology, values and governance.

This dilemma defines the Xi era. Propaganda campaigns sustain short-term legitimacy, but they also entrench the very constraints that erode it. As the 2027 Party Congress approaches, the question is whether Beijing can relax its control enough to restore vitality — or whether it will remain locked in a cycle of over-centralization, trading dynamism for discipline.

Eighty years after the end of World War II, China stands at a crossroads. Internationally, it seeks to challenge U.S. primacy through diplomatic activism and narrative competition. Domestically, it tightens ideological control to maintain cohesion amid economic stagnation and social anxiety. The two dynamics are inseparable: Global ambition requires internal unity, yet internal repression constrains the creativity that global leadership demands.

Xi’s China projects confidence abroad but governs through caution at home. The regime’s survival depends on sustaining both stories at once — convincing the world that China’s rise is irreversible and convincing its citizens that optimism is patriotic truth. Whether this balance can hold will shape not only China’s trajectory toward 2027, but also the evolving architecture of the postwar international order.

(Photo Credit: Xinhua News Agency/AFLO)

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on Nov 16, 2025:

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s

challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as

technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of

Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Visiting Senior Fellow

Naoko Eto is a professor in the Department of Political Science at Gakushuin University. Her main research interests include East Asian affairs and Japan-China relations. She is a member of the Expert Committee on Industrial and Technological Infrastructure Strengthening for Economic Security at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Industrial Structure Council, METI and the Customs and Foreign Exchange Council at the Ministry of Finance (MOF). She was also a visiting research fellow at the School of International Studies, Peking University, the East Asian Institute, Singapore National University, and a visiting senior fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. [Concurrent Position] Professor, Department of Political Science, Gakushuin University

View Profile-

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27

The Supreme Court Strikes Down the IEEPA Tariffs: What Happened and What Comes Next?2026.02.27 -

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 Navigating Uncertainty in U.S. Space Policy: Decoding Elon Musk’s Influence2025.04.09

Navigating Uncertainty in U.S. Space Policy: Decoding Elon Musk’s Influence2025.04.09