Beijing’s ‘Globalist’ Agenda Under Trump 2.0

As 2025 comes to a close, it’s worth reflecting on the historical significance of a year that marked the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II as well as the founding of the United Nations.

China, not surprisingly, has taken advantage of these symbolic milestones to underscore its self-image as a “guardian of the postwar order.”

At the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in September, for example, Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled a new diplomatic framework, the Global Governance Initiative (GGI), which Foreign Minister Wang Yi calls “a blueprint for humanity’s shared future.”

The GGI’s timing is deliberate. Beijing aims to link the “Victory in the War of Resistance Against Japan” with the U.N.’s 80th anniversary, positioning itself as the moral and historical heir to the post-1945 order.

In its GGI concept paper, the Chinese Foreign Ministry declares that the U.N., “established in the aftermath of the lessons of 80 years ago,” has made historic contributions to peace and development. It pledges that China will “firmly uphold the international system with the U.N. at its core and the international order based on international law.”

Yet the same document outlines three structural flaws in the current governance system: The “historical injustice” of underrepresentation of developing and emerging economies; the erosion of U.N. authority amid deepening geopolitical confrontation; and the system’s limited effectiveness in addressing new challenges such as stalled Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), generative AI and climate change.

China thus calls for expanding the Global South’s voice to “restore fairness” in world governance — while implicitly criticizing the United States’ “unilateralism and Cold War mentality.” The GGI therefore signals China’s attempt to rebuild the international order from within, portraying itself as both defender and reformer of the U.N.-centered system.

For a socialist state, the term “global governance” was once viewed as a bourgeois, Western academic construct. Yet since the early 2000s, Chinese scholars such as Yu Keping, director of the Center for Chinese Government Innovations at Peking University, began theorizing on global governance within Chinese Communist Party (CCP) discourse.

After China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, globalization (quanqiuhua) was celebrated by the CCP as an engine of growth. Then, following the 2008 global financial crisis, Beijing’s role in the Group of 20 expanded, linking its narrative to “global governance reform.”

Under Xi’s leadership, since the 18th Party Congress in 2012, the term entered official documents and became operational through initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and China’s Belt and Road initiative. The GGI represents the culmination of these efforts — a “globalist manifesto” asserting China’s identity as an institutional actor shaping the norms and rules of the international order.

‘America First’

The contrast with the second Trump administration could not be clearer. Early in 2025, U.S. President Trump announced the United States’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO) and signaled renewed plans to leave UNESCO, underscoring Washington’s retreat from multilateral institutions. The U.S. State Department accused UNESCO of being overly focused on the globalist and ideological agenda of the SDGs, inconsistent with Trump’s “America First” foreign policy.

In his U.N. General Assembly address in September, Trump again denounced “globalists,” casting alliances, aid and multilateral cooperation as shackles on U.S. freedom. At the same time, his administration’s moves to dismantle the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and freeze development contracts have reduced American engagement, leaving developing countries increasingly drawn to Chinese financing and development frameworks.

This U.S. retrenchment creates a vacuum of global governance leadership — one that China is eager to fill through initiatives like the GGI. By framing its message in the language of “fairness,” “inclusivity” and “shared development,” Beijing avoids overt confrontation with the West while presenting itself as a normative alternative to U.S. dominance. In effect, China’s “globalist” activism functions as a counter-narrative to Washington’s “America First” retrenchment.

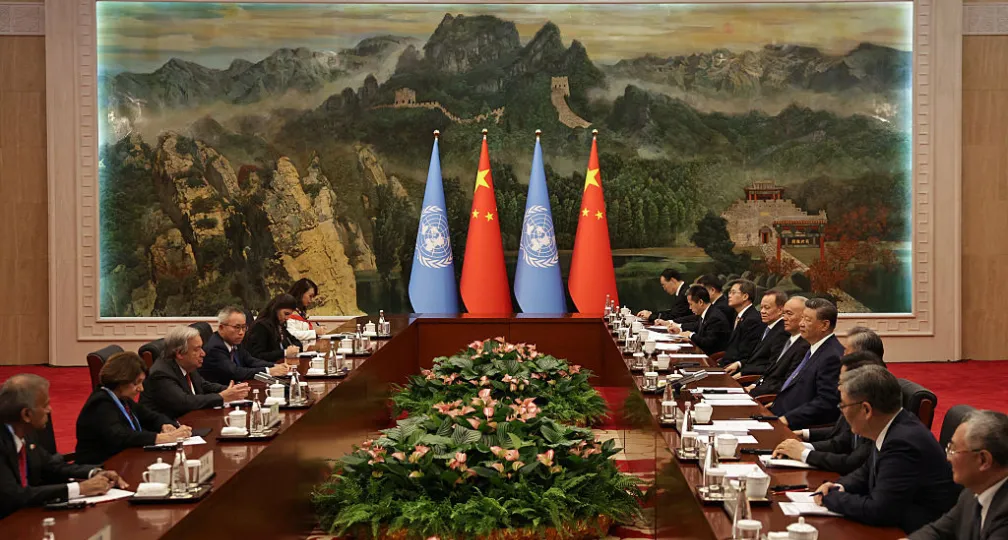

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres publicly “welcomed” the GGI during the September SCO meeting, praising it as an initiative “rooted in multilateralism and supportive of the U.N.-centered international system.” While partly diplomatic courtesy, the statement reflects pragmatic recognition of China’s growing financial and institutional footprint within the U.N. system.

Beijing is now the second-largest contributor to the U.N. regular budget and to many of its specialized agencies. China’s Global Development and South-South Cooperation Fund finances multiple U.N. projects, and the U.N. Development Program recently agreed to establish a Global Center for Sustainable Development in Shanghai.

The U.N. secretary-general’s “welcome,” therefore, may be read as a conditional endorsement — a signal of willingness to cooperate with China within the U.N. framework, while preserving institutional balance.

Nevertheless, China’s substantive contribution to international governance remains constrained. Delays in its assessed payments have occasionally strained U.N. finances, and its voluntary contributions remain limited compared to those of Western donors.

Still, Beijing has systematically sought to expand its institutional influence — securing leadership roles in agencies such as the International Telecommunication Union and the Food and Agriculture Organization, as well as embedding its political phrases like “community with a shared future for mankind” in U.N. documents.

These trends have heightened Western concern over Beijing’s growing normative and bureaucratic presence within multilateral institutions.

Shared Responsibility

China’s “globalist” agenda, encapsulated in the GGI, carries a dual message: solidarity with the Global South and an implicit challenge to the Western-led postwar order. By defining the Global South broadly to include emerging powers such as China and Russia, Beijing seeks to align these states under a shared banner of “reform” while reinforcing its own leadership claim.

As competition between Washington and Beijing intensifies across military, economic and technological domains, the governance sphere is becoming an asymmetric battlefield: The U.S. withdraws, while China steps forward to shape norms. This dynamic allows Beijing to project legitimacy as a responsible stakeholder, even as skepticism persists among many states.

What the international community now requires is a clear-eyed assessment of China’s narrative — discerning substance from symbolism — and a realistic appraisal of institutional reform needs.

While Beijing’s motives may be self-interested, the growing political and economic weight of the Global South warrants greater participation and shared responsibility in providing international public goods.

For Japan, this moment calls for a strategic recalibration: to monitor China’s evolving role, confront the U.N.’s institutional fatigue and propose governance reforms that reflect the perspectives and demands of Global South nations.

Only through such proactive engagement can Tokyo contribute to shaping a balanced, rules-based international order fit for a new reality.

(Photo Credit: Pool / Getty Images)

[Note] This article was posted to the Japan Times on Nov 28, 2025:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2025/11/28/japan/beijings-globalist-agenda/

Geoeconomic Briefing

Geoeconomic Briefing is a series featuring researchers at the IOG focused on Japan’s challenges in that field. It also provides analyses of the state of the world and trade risks, as well as technological and industrial structures (Editor-in-chief: Dr. Kazuto Suzuki, Director, Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG); Professor, The University of Tokyo).

Senior Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow of the China Group at the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG). Doi specializes in China and the world (geoeconomic issues, such as development finance and emerging technologies), and global governance in the social development sectors, including education and health. He graduated from the University of Kitakyushu with a B.A. in International Relations (Contemporary China Studies) and a Master of Public Policy from the University of Tokyo. Doi joined the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 2008, where he worked on the implementation of the Japanese government’s foreign aid to China at the JICA Beijing Office and conducted financial investments in economic and social infrastructure, sovereign credit risk analysis and research on China’s development cooperation with the Global South at the Africa Department. In 2018, he began his doctoral studies in the Department of Education Economics at Peking University in China, where he received his PhD in Public Policy in 2022. Doi served as a senior researcher and advisor at Diinsider Co., Ltd, a China-based international development consultancy, and as an adjunct researcher at the Center for the Study of International Cooperation in Education, Waseda University, before being appointed to his current position in August 2024. His research has been published in books by international publishers, including Routledge and Springer Nature, as well as in international peer-reviewed journals such as Development Policy Review, Higher Education Research & Development, Public Health Action, and Compare. [Concurrent Positions] Adjunct Researcher, Center for the Study of International Cooperation in Education, Waseda University, Japan. (2023-Present) Visiting Lecturer, Department of International Business and Management, Kanagawa University, Japan. (2025-2026).

View Profile-

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 -

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13

What Takaichi’s Snap Election Landslide Means for Japan’s Defense and Fiscal Policy2026.02.13 -

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12

Challenges for Japan During the U.S.-China ‘Truce’2026.02.12 -

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09 -

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04

Orbán in the Public Eye: Anti-Ukraine Argument for Delegitimising Brussels2026.02.04 Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13

Fed-Treasury Coordination as Economic Security Policy2026.02.13 When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29

When Is a Tariff Threat Not a Tariff Threat?2026.01.29 Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07

Oil, Debt, and Dollars: The Geoeconomics of Venezuela2026.01.07 India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09

India and EU Sign Mother of All Deals2026.02.09